Volume

26, No. 9 – September 2013

Volume 26, No. 9

Editor: Stephen L. Seftenberg

Website:

www.CivilWarRoundTablePalmBeach.org

President's Message

Happy Anniversary, Round Table!

We owe our inception to the vision and determination of Civil War

enthusiast, Robert (Bob) S. Godwin. In 1987 Bob secured a list of Palm

Beach County subscribers to the "Civil War Times." He personally

contacted each one and invited them to join a fledgling Round Table. Bob

was so excited to have three other people who shared his interest at the

first meeting on September 16, 1987. The charter members who attended

were Rodney Dillon, Bob Godwin, Joel Gordon, and Greg Parkinson.

Unfortunately, Bob Godwin and his lovely wife, Lillian, died tragically

in an auto accident on June 15, 1990 en route to Virginia Tech’s

"Campaigning with Lee" seminar.

I know that Bob would draw great satisfaction knowing that the Round

Table has grown to over sixty-five members, meets monthly, and will be

celebrating twenty-six successful years in Palm Beach County.

Eleven years ago I never expected to be writing the September, 2013,

President’s Message. I greatly appreciate the confidence you have in me.

Thank you to the members for all your assistance and guidance through

the years. Every time you volunteer or give financial support to the

Round Table, it makes us a stronger and more viable organization. In

this way the Round Table will continue to evolve and change with the

needs of the membership.

Gerridine LaRovere, President

September 11, 2013 Program

One of our favorite member-speakers, Janell Bloodworth, will

entertain and educate about "Emilie Todd Helm, President Abraham

Lincoln's Confederate Sister-in-Law."

August 10, 2013 Program

The Red River Campaign – "One Damn Blunder From Beginning to

End"

If someone not in the Roundtable were asked, "What was the largest

campaign in the American Civil War west of the Mississippi River?" the

response probably would be, "There were battles west of the

Mississippi?" True, these battles were not as famous as those in

Virginia or Pennsylvania or Tennessee or Georgia, but they were

important. In fact, the Red River Campaign, the Confederacy’s last major

victory, delayed the end of the war and destroyed a Union general’s

political career.

Steve pointed out that we actually have an embarrassment of riches

with respect to the Red River Campaign. In chronological order, oldest

is the Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War,

1863-1866 (U. S. Congress 1866), reprinted in 1977, 401 pages packed

with copies of original sources in very small print. Next, The Red

River Campaign – Politics and Cotton in the Civil War, a seminal

work by Professor Ludwell H. Johnson, Professor Emeritus of

History at The College of William and Mary, published in 1958 and

republished in 1995) which Steve used to outline his talk. Then comes

War Along the Bayous, by William R. Brooksher, U. S. Army Brigadier

General, Retired, published in 1998; followed by The Red River

Campaign and the Loss by the Confederacy of the Civil War, by

Michael J. Forsythe a then active U. S. army officer, published in 2002;

then came two related books, One Damn Blunder From Beginning to End

and Through the Howling Wilderness: the Red River Campaign and

Union Failure in the West, both by Gary D. Joiner, an associate

professor at Louisiana State University, and both published in 2006;

then Little to Eat and Thin Mud to Drink: Letters, Diaries, and

Memoirs from the Red River Campaign, 1863-1864, edited by Joiner,

published in 2007; and finally, Richard Taylor and the Red River

Campaign of 1864, by Samuel W. Mitcham, Jr., published in 2012,

another retired military man with over 40 books published.

They say that history is always written by the victors, but all of

the authors listed are or were Southerners and this sometimes shows in

the way they write. That is certainly true of Professor Johnson, who

has written extensively on the history of the Civil War, and who has

a distinctly pro-Southern tilt. At least one critic called his

body of work, "the Southern version" which attempts to "redeem the honor

of the Confederacy." The same critic said, "Johnson preferred Lee to

Grant as a military commander and Jefferson Davis to Lincoln as a war

president; and he saw the South as defending itself against an

aggressive North." In an earlier book, North Against South: The

American Iliad, 1848-1877, Johnson went so far as to contend that

the horrors of Reconstruction were but a continuation of atrocities

perpetuated during the war by Union armies. Nevertheless, Johnson’s book

accurately details all the reasons the Union saw for waging the

campaign.

Foremost was POLITICS: The year 1864 was an election

year and President Lincoln thought that if he could get Louisiana back

into the Union before the election in November, he could count on its

electoral votes.

Second was COTTON: Shreveport, Louisiana, and Northeast

Texas were major sources of cotton, which if it could be smuggled out by

blockade runners and sold to British textile mills, would pay for

armaments and supplies for the Confederacy. The textile mills in

Massachusetts and other New England states also wanted that cotton and

speculators with political connections smelled immense profits to be

gained by having the cotton confiscated as contraband and shipped

North.

Third and by no means least, was GEOPOLITICS: A

successful invasion would allow antislavery settlers to

flood Texas as they did in Kansas in the 1850's. Northern abolitionists

and other groups hoped to create ‘five or six’ free states out of the

single slave state of Texas.

Finally,

there was FOREIGN POLICY: France had propped up

Maximillian as Emperor of` Mexico. Lincoln and his military strategists

feared the French might grab parts of Texas lost by Mexico in the

Mexican War for its Mexican puppet regime. Finally,

there was FOREIGN POLICY: France had propped up

Maximillian as Emperor of` Mexico. Lincoln and his military strategists

feared the French might grab parts of Texas lost by Mexico in the

Mexican War for its Mexican puppet regime.

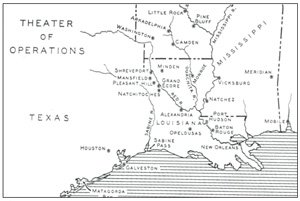

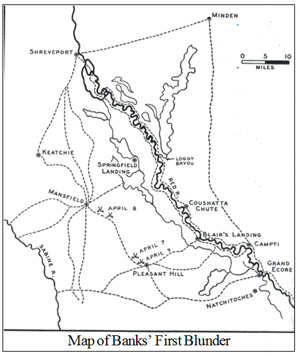

The map shows the Theater of Operations. Three different

strategies were debated: U. S. Grant, commander of U. S. forces in the

West, wanted to shut the door on smuggling by taking Mobile, Alabama.

General Nathaniel P. Banks, who would command the invasion army,

preferred an amphibious landing at Sabine Pass and an advance toward

Houston and had even made a feeble and unsuccessful unauthorized landing

at Sabine Pass in September 1863. General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck,

derisively nicknamed "Old Brains," however preferred moving up the Red

River to take Shreveport, and of course his views prevailed. By the time

Grant succeeded Halleck as General-in-Chief, the die had been cast and

the troops needed to take Mobile were already west of the Mississippi.

Halleck’s plan called for Banks to take 30,000 plus Union soldiers up

the Red River to Shreveport then west to Tyler, Texas, and Marshall,

Texas. Accompanying him was the largest Union naval force ever assembled

west of the Mississippi, under the command of Admiral David Dixon

Porter. What could possibly go wrong? Just about everything!

First

came Halleck’s blunder, which may have doomed the entire

enterprise to failure even before it started: he never named a supreme

commander (no one wanted Banks to be in charge and it is difficult to

imagine Banks taking orders from Porter). Instead Halleck "expected" the

two egotistical leaders to "cooperate." First

came Halleck’s blunder, which may have doomed the entire

enterprise to failure even before it started: he never named a supreme

commander (no one wanted Banks to be in charge and it is difficult to

imagine Banks taking orders from Porter). Instead Halleck "expected" the

two egotistical leaders to "cooperate."

It’s time to introduce you to the three major players in this story:

Nathaniel P. Banks, then 48 years old, was already a very popular

politician (Governor of Massachusetts 1858-1861), but had fallen short

of the Republican presidential nomination in 1860. After the war

started, Banks had been considered by Lincoln for a cabinet post but

instead was one of his first "political" generals. Banks hoped to use a

successful campaign as a springboard to nomination and election as

president in1864. Johnson alleges that Banks hoped to ship thousands of

bales of cotton back to Massachusetts, making himself a rich hero in the

process, while keeping cotton speculators with important political

connections happy. Johnson admits that Banks, with one exception did not

give the speculators any favors. The one exception came when President

Lincoln was duped into signing a note instructing Banks to do everything

in his power to help Samuel Casey, a former congressman and now a cotton

speculator. What Casey hoped to do may not have been entirely legal but

Banks had no choice but to give him free reign. In any case, Banks had

many reasons of his own both to go on this campaign one of which was to

make sure

cotton

got back to Northern mills by hook or crook. Banks’ army was an

ill-suited combination of battle-hardened cocky Western troops, taken

from Sherman’s army, commanded by 48-year old Gen. Andrew Jackson Smith

and raw recruits from New England that Banks had recruited and brought

with him to New Orleans, commanded by 48-year old William Buel Franklin.

Both A. J. Smith and Franklin were West Point grads ("P’inters" as we

found out last month). There was little or no love lost between the two

Corps. Significantly, Franklin was part of Banks’ team, while A. J.

Smith was not. cotton

got back to Northern mills by hook or crook. Banks’ army was an

ill-suited combination of battle-hardened cocky Western troops, taken

from Sherman’s army, commanded by 48-year old Gen. Andrew Jackson Smith

and raw recruits from New England that Banks had recruited and brought

with him to New Orleans, commanded by 48-year old William Buel Franklin.

Both A. J. Smith and Franklin were West Point grads ("P’inters" as we

found out last month). There was little or no love lost between the two

Corps. Significantly, Franklin was part of Banks’ team, while A. J.

Smith was not.

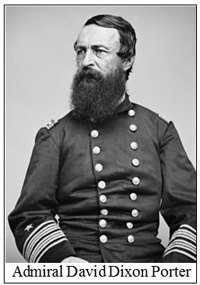

Next on stage is Admiral David Dixon Porter, 51, son of a famous

naval hero, second man to be made an admiral, following his adoptive

brother, David G. Farragut, a midshipman at 10, victor in the capture of

New Orleans and leader of the Mississippi River Squadron that helped

Grant capture Vicksburg, Port Hudson and other Confederate positions so

the Mississippi, in Lincoln’s famous phrase, "could flow unvexed to the

ocean." It is significant to note that Porter hated politics and

politicians and this shadowed his relationship with Banks.

Porter’s

"brown water navy" consisted of more than 90 vessels (a "marvelous

mixture" of ironclads, river monitors, tinclads, timberclads, a ram and

support vessels), a separate Marine Brigade of 1,000 men and another

separate force under the Quartermaster with its own fleet. Porter wanted

all this firepower because he had word of Shreveport’s strong defenses,

including many Confederate ironclads and submarines. Porter’s

"brown water navy" consisted of more than 90 vessels (a "marvelous

mixture" of ironclads, river monitors, tinclads, timberclads, a ram and

support vessels), a separate Marine Brigade of 1,000 men and another

separate force under the Quartermaster with its own fleet. Porter wanted

all this firepower because he had word of Shreveport’s strong defenses,

including many Confederate ironclads and submarines.

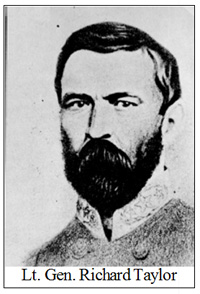

Third to take the stage is Confederate Major General Richard Taylor,

only 38, a Harvard student who graduated from Yale, a member of the

famed Skull & Bones Society, a very rich Louisiana plantation owner, an

enlightened slave owner according to Frederick Law Olmstead, a skilled

politician, military historian, son of former President Zachary Taylor,

brother-in-law of President Jefferson Davis and the most popular

Confederate general west of the M ississippi.

In the early stages of the war, Stonewall Jackson used Taylor's

"Louisiana Tigers" as an elite strike force in the Shenandoah theater.

When Taylor was promoted to Major General on July 28, 1862, he was the

youngest major general in the Confederacy. He was put in command of the

District of West Louisiana, with few troops or other war material.

Nevertheless, in a series of battles with Banks in Southern Louisiana,

he came close to recapturing New Orleans, but had to retreat when Port

Hudson was captured. ississippi.

In the early stages of the war, Stonewall Jackson used Taylor's

"Louisiana Tigers" as an elite strike force in the Shenandoah theater.

When Taylor was promoted to Major General on July 28, 1862, he was the

youngest major general in the Confederacy. He was put in command of the

District of West Louisiana, with few troops or other war material.

Nevertheless, in a series of battles with Banks in Southern Louisiana,

he came close to recapturing New Orleans, but had to retreat when Port

Hudson was captured.

Now for the campaign itself: After many delays that vexed President

Lincoln, the expedition got underway on March 10, 1864, with Franklin

marching north along the Red River from Port Hudson while Smith went

north aboard Porter’s troop ships. Banks and his army of over 32,000

faced Taylor, who initially had 7,000 or so men and never more than

8,800 men. Things went well at the start. Fort DeRussy, 20 miles south

of Alexandria, called the "Confederate Gibraltar," was the first

obstacle. However, as with Singapore in World War II, its guns faced the

river and its rear was poorly guarded. Attacking from the rear, A. J.

Smith captured the fort on March 14.

By

March 31, Banks was in Natchitcohes (pronounced Nakaktish). At this

point Banks made the first of five blunders (shown on the

map to the right). Instead of continuing to drive northwest along the

Red River in conjunction with the U. S. Navy, Banks chose a narrow

inland stage coach road that ran from Grand Ecore through Pleasant Hill

and Mansfield before swinging north to Shreveport. This blunder meant

that he had to carry all of his own supplies and that he would be out of

touch with Porter’s gunboats. The source of this blunder, according to

Joiner, was a river pilot named Wellington W. Withinberry, who--to

protect his own cotton stored upstream--single-handedly sealed the fate

of the Union army by convincing Banks to move inland. (Joiner, One

Damn Blunder, xv). Joiner considers By

March 31, Banks was in Natchitcohes (pronounced Nakaktish). At this

point Banks made the first of five blunders (shown on the

map to the right). Instead of continuing to drive northwest along the

Red River in conjunction with the U. S. Navy, Banks chose a narrow

inland stage coach road that ran from Grand Ecore through Pleasant Hill

and Mansfield before swinging north to Shreveport. This blunder meant

that he had to carry all of his own supplies and that he would be out of

touch with Porter’s gunboats. The source of this blunder, according to

Joiner, was a river pilot named Wellington W. Withinberry, who--to

protect his own cotton stored upstream--single-handedly sealed the fate

of the Union army by convincing Banks to move inland. (Joiner, One

Damn Blunder, xv). Joiner considers

Banks’ refusal of either a naval or cavalry reconnaissance up the

river "is unforgivable" (Joiner, Through the Howling Wilderness,"

p. 76). From the beginning of the Red River Campaign, Taylor could only

delay the Union advance, but Taylor had a surprise waiting for Banks and

his men once they left the river and were approaching Mansfield.

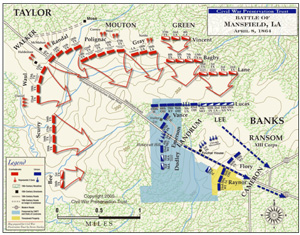

On

April 8, 1864, Taylor, with 8,800 men, surprised the head of Banks'

20-mile long column, driving the Yankees back with heavy casualties and

capturing many supply wagons before stopping due to the darkness. Banks

was able to commit no more than 12,000 of his 32,000 men and Taylor was

able to outnumber them at every important point of contact. A look at

the map of the battle shows this. The rest of the Union troops were

toiling through dust and mud miles behind and missed the battle. This

battle’s outcome was determined by a series of additional blunders by

Banks. Bank’s second blunder was to "accept battle at the

head of a column 20 miles long at the hands of an enemy formed in

complete order of battle, in a position previously chosen by the enemy,

and where Banks’ artillery could not On

April 8, 1864, Taylor, with 8,800 men, surprised the head of Banks'

20-mile long column, driving the Yankees back with heavy casualties and

capturing many supply wagons before stopping due to the darkness. Banks

was able to commit no more than 12,000 of his 32,000 men and Taylor was

able to outnumber them at every important point of contact. A look at

the map of the battle shows this. The rest of the Union troops were

toiling through dust and mud miles behind and missed the battle. This

battle’s outcome was determined by a series of additional blunders by

Banks. Bank’s second blunder was to "accept battle at the

head of a column 20 miles long at the hands of an enemy formed in

complete order of battle, in a position previously chosen by the enemy,

and where Banks’ artillery could not be used because of the trees in the way" and before he could organize

his army. Banks was impatient and ordered his cavalry commander, Albert

Lee, to charge unassisted across an open field into hidden rebel guns.

Only Lee’s adamant refusal to obey this suicidal order kept this battle

from being a total rout before it really even started. Banks’

third and most serious blunder had been to set the order of

march with the cavalry in front, "followed immediately by 300 wagons at

Franklin’s insistence so as not to delay his own supply train." Then

came 2,500 U. S. Colored Troops to guard the wagon train. Then came

Franklin’s 15,000 infantry. Then came 700 more wagons. Finally came A.

J. Smith’s 7,500 angry veterans. The red clay stage road was so narrow

the men could not march more than 4 abreast and was either a dust storm

when dry or slippery muck when wet. One Union cavalryman called the area

"a howling wilderness." Most of the supply wagons were captured by the

rebels when the Union teamsters beat a hasty retreat. Banks and Franklin

failed to see that the two

be used because of the trees in the way" and before he could organize

his army. Banks was impatient and ordered his cavalry commander, Albert

Lee, to charge unassisted across an open field into hidden rebel guns.

Only Lee’s adamant refusal to obey this suicidal order kept this battle

from being a total rout before it really even started. Banks’

third and most serious blunder had been to set the order of

march with the cavalry in front, "followed immediately by 300 wagons at

Franklin’s insistence so as not to delay his own supply train." Then

came 2,500 U. S. Colored Troops to guard the wagon train. Then came

Franklin’s 15,000 infantry. Then came 700 more wagons. Finally came A.

J. Smith’s 7,500 angry veterans. The red clay stage road was so narrow

the men could not march more than 4 abreast and was either a dust storm

when dry or slippery muck when wet. One Union cavalryman called the area

"a howling wilderness." Most of the supply wagons were captured by the

rebels when the Union teamsters beat a hasty retreat. Banks and Franklin

failed to see that the two

wagon

trains would box in Franklin’s infantry, hindering both their advance

and their retreat. Joiner, in Through the Howling Wilderness, p

77-79, notes a fourth blunder by Banks: "Banks’ use of

only one road set the stage for disaster. His failure to have his

cavalry fan out ahead and seek other routes qualifies as one of the

greatest blunders of the Civil War." By all accounts, the Battle of

Mansfield was "one of the most humiliating Union defeats of the war." wagon

trains would box in Franklin’s infantry, hindering both their advance

and their retreat. Joiner, in Through the Howling Wilderness, p

77-79, notes a fourth blunder by Banks: "Banks’ use of

only one road set the stage for disaster. His failure to have his

cavalry fan out ahead and seek other routes qualifies as one of the

greatest blunders of the Civil War." By all accounts, the Battle of

Mansfield was "one of the most humiliating Union defeats of the war."

A dirty little secret must be revealed about Taylor’s forces – a

substantial portion of his army consisted of parole violators – veterans

who had surrendered at Vicksburg and Port Hudson. What they were doing

was highly illegal and the punishment for their crime was death. They

apparently had no homes to go home to and the Southern officers and men

quietly welcomed them into their ranks.

The next day, April 9, Taylor attacked Banks at Pleasant Hill.

Technically Taylor lost the battle because of the solid stand of A. J.

Smith's men, but this battle put an end to the campaign because Banks

now commits a fifth and final blunder that sealed the fate

of his political hopes by retreating that night, instead of regrouping

and attacking in the morning. Steve stated that he had no doubt that if

Grant or Sherman (or A. J. Smith) had been in command, he would have

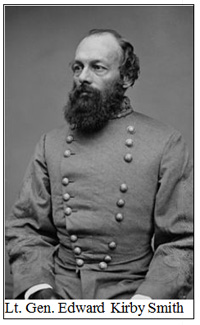

attacked the next morning and probably prevailed. Edward Kirby Smith,

40, another P’inter, and as commander of the Confederate Department of

the Trans-Mississippi, reported to President Davis after the battle that

Taylor’s forces had been "repulsed and were broken and scattered and

completely paralyzed" and had Banks attacked, he very well could have

walked to Shreveport. A. J. Smith, as noted before, not part of Banks’

inner circle, agreed with Kirby Smith and confronted Banks, contending

that the Union army should follow up its victory, but Banks would not

change his mind. A. J. Smith then asked Franklin to weigh in but

Franklin would not do so. A. J. Smith even suggested that Franklin

arrest Banks and take over command. Franklin said, "Smith, don’t you

know this is mutiny?" Smith silently left to carry out his orders. The

Union soldiers could not believe a retreat had been ordered and

serenaded Banks, chanting:

"In 1861, we all skedaddled to Washington.

In 1864, we all skedaddled to Grand Ecore."

In

a confidential letter to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Wells dated April

28, 1864, Admiral Porter bluntly agreed with the soldiers: "The only man

here who possesses the entire confidence of the troops is General A. J.

Smith, and if he were placed in command of this army he would, I am

convinced, retrieve all its disasters." [Joint Committee Report,

page 253] In

a confidential letter to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Wells dated April

28, 1864, Admiral Porter bluntly agreed with the soldiers: "The only man

here who possesses the entire confidence of the troops is General A. J.

Smith, and if he were placed in command of this army he would, I am

convinced, retrieve all its disasters." [Joint Committee Report,

page 253]

At this point Kirby Smith, Taylor’s superior officer, may have saved

Banks and Porter from total defeat by taking most of Taylor's troops

away to defeat Union General Frederick Steele's movement south from

Little Rock, Arkansas towards Shreveport. Taylor was furious, believing

that Banks' troops were demoralized and ripe for capture. The

disagreement festered and led to Taylor's transfer shortly after the end

of the campaign.

The Union retreat from Pleasant Hill to Alexandria was not a pleasure

trip because of the loss of the supply train and constant attacks by the

Confederate cavalry. In a letter dated May 4, 1864, Union Private Thomas

Hayden wrote a letter to a friend in which he says, "Pleasant Hill was

not exactly a victory for us. Gen. Banks thought he had seen

enough of that part of the country so, April 21, we began the great

retreat to Alexandria. We marched day and night, with the rebs all round

us, fighting all the time. It was an awful hard march, Jim. Little

to eat and thin mud to drink. We arrived at Alexandria

Apr. 26, all tired out. Soldiering out here is no joke." [Little to

Eat and Thin Mud to Drink, p. 179-80.]

Porter, 51, had committed his own almost fatal blunder

by steaming North of the rapids at Alexandria with all his vessels,

putting the most heavily armed vessels with the most draft first in

line. Many of Porter’s gunboats and troop ships needed 7 feet of water

but the river at Alexandria was often less than 3 feet deep. Porter

repeatedly bragged that he could take his fleet "wherever the sand was

damp." [One Damned Blunder p 67] Once Banks began his hasty

retreat from Pleasant Hill, Porter began a slow retreat down a river

with not enough water and too many sandbars. Taylor tried repeatedly to

cut off the Union navy’s retreat Capt. Thomas O. Selfridge testified to

the Joint Committee that "the return of the fleet was fraught with

peril." [Forsythe, The Red River Campaign, page 90]. As noted a

moment ago, Taylor’s thinned-out forces harassed Banks’ hungry troops,

but Banks was able to retreat over 90 miles to Alexandria. He could go

no farther because most of Porter’s squadron was trapped north of

the rapids! Banks, under orders from Grant, could not desert

Porter here because the Confederates would have sunk or captured the

entire squadron.

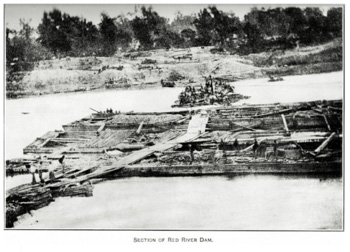

An

ingenious Wisconsin engineer, Col. Joseph Bailey, using skills learned

in floating logs down rivers in lumbering operations, rescued Porter

from potential disaster with what has been labeled as "one of the most

imaginative engineering feats in military history." Taking 3,000 men

Bailey built a dam over 700 feet wide in just 10 days, using nothing but

trees, rocks, bags of dirt and hundreds of bales of confiscated

cotton, then sank four barges filled with stone to fill the gap and

raise the level of the river. The dam lasted just long enough to let the

Union vessels go roaring down the river to safety. A contraband watching

from the shore said, "Before God, what won’t the Yankees do next?" With

the navy no longer in jeopardy, Banks was free to continue his retreat.

Taylor’s diminished force could harass and continue inflicting

casualties on the Union soldiers and sailors, but he lacked the manpower

to block and defeat them. Taylor made two last efforts to stop Banks, at

Mansura on May 16 and at Yellow Bayou on May 18, but the Union army was

able to retreat across the Atchafalaya River to safety. An

ingenious Wisconsin engineer, Col. Joseph Bailey, using skills learned

in floating logs down rivers in lumbering operations, rescued Porter

from potential disaster with what has been labeled as "one of the most

imaginative engineering feats in military history." Taking 3,000 men

Bailey built a dam over 700 feet wide in just 10 days, using nothing but

trees, rocks, bags of dirt and hundreds of bales of confiscated

cotton, then sank four barges filled with stone to fill the gap and

raise the level of the river. The dam lasted just long enough to let the

Union vessels go roaring down the river to safety. A contraband watching

from the shore said, "Before God, what won’t the Yankees do next?" With

the navy no longer in jeopardy, Banks was free to continue his retreat.

Taylor’s diminished force could harass and continue inflicting

casualties on the Union soldiers and sailors, but he lacked the manpower

to block and defeat them. Taylor made two last efforts to stop Banks, at

Mansura on May 16 and at Yellow Bayou on May 18, but the Union army was

able to retreat across the Atchafalaya River to safety.

This ended the campaign. When pressed for his opinion, General

William Tecumseh Sherman called it "one damn blunder from beginning

to end." Steve added: militarily, politically and

economically.

The Federals left a path of destruction in their wake, burning houses

and barns and stealing or killing livestock all the way south from Grand

Ecore and even leveling Alexandria by firing the town. Johnson singles

out A. J. Smith’s battle-hardened westerners (called "gorillas" by the

rebels) as the main culprits, though the less-experienced Easterners

recruited by Banks did their share of mischief. In addition, the

Confederates burned the cotton rather than letting it fall into Union

hands. In any event, the residents had to choose between fleeing and

starving and preserved their resentments against Yankees for

generations.

Professor Johnson argues that the Red River campaign was

"unnecessary," that it delayed the end of the war and that it ran up the

war’s cost in blood and money. Banks' inglorious expedition tied up as

many as 20,000 veteran soldiers who could have been better used to

reinforce Sherman's army against Atlanta or to attack Mobile, as Grant

wanted. Instead, these men were stuck west of the Mississippi, allowing

General Polk and 20,000 rebels to leave Mobile to help Joe Johnston

defend Atlanta.

The army under Banks and the navy under Porter failed to cooperate as

Halleck had hoped they would, and instead often competed in a race to

seize cotton. Even here the campaign was a failure because most of the

cotton Banks had hoped to glean was burned on the approach of the

Federals or lost in the hasty retreat from Grand Ecore. And the project

of making free states out of Texas disappeared with the Union army’s

retreat. Lastly, Banks' Presidential hopes were also crushed by his

humiliating failures during the campaign. President Lincoln relieved him

of field command and returned him to Washington, D. C., to lobby for the

president’s Reconstruction program.

Now the Radical Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War jumped in

to "investigate" the "disastrous" campaign and "Banks joined the unhappy

company of men who were subjected to the prejudicial scrutiny of Ben

Wade and his colleagues." "Any evidence tending to reflect discredit on

the administration was welcome" and Lincoln’s alleged connection to

cotton trading was fodder for the enemies of Lincoln’s Reconstruction

plans. Also of interest to the committee were stories of swarms of

speculators accompanying the army and allegedly enjoying the assistance

and protection of Banks.

Admiral Porter testified that "the whole affair was a cotton

speculation . . . a big cotton raid." Porter and the committee

conveniently ignored the fact that "wherever cotton was found, [the

navy] seized it." Not for nothing was Porter given the nom de guerre

"The Thief of the Mississippi." Johnson concluded that "Banks gave

no one who accompanied the expedition any special trading privileges. .

. . Of course, when Samuel L. Casey and William Butler" (the shady

brother one of my favorite Civil War characters, Benjamin Franklin

Butler) "appeared with a pass bearing Lincoln’s signature, Banks was

obliged to give them a free hand." One witness fabricated an absurd tale

that Gov. Richard Yates of Illinois (one of Lincoln’s best friends) had

gone to New Orleans as part of a scheme concocted by Yates and Banks to

make the latter President by raising a slush fund trading in cotton

which would be used to buy the nomination of Banks.

Porter’s postwar career bloomed under President Grant and he did much

to reform the Naval Academy and naval policy, but soon rubbed too many

important people the wrong way with his brusque manner and total lack of

political savvy. By 1868 he had been put out to pasture.

On the Confederate side, Taylor was an excellent general and his

ideas for pursuing Banks made more sense than Kirby Smith's decision to

block Steele’s move south from Arkansas. Nathan Bedford Forest said: ".

. .if we’d had more like him, we would have licked the Yankees long

ago." After the war, he moved to New York and wrote his much-praised

memoirs, "Destruction and Reconstruction," became active in Democratic

Party politics and opposed Radical Reconstruction.

Finally, both armies joined to lay waste a good portion of Western

Louisiana which did not recover for many decades. The population

harbored great animosity toward the Federal government and the

Republican Party for generations.

Forsythe, something of a contrarian, contends that the Red River

Campaign was "one of the most successful campaigns conducted by any

Confederate army during the Civil War. . . . Through sheer audacity and

superior leadership, General Taylor turned back the invaders, driving

them all the way to the Mississippi River. In the process, the

Confederates . . . [captured] a huge supply train, dozens of field guns,

thousands of stands of small arms and over a thousand prisoners. [As a

result,] the Rebel government was able to maintain territorial integrity

of the region west of the Mississippi until the very last days of the

war." [Forsythe, 119-123] Forsythe contends that it might

have been possible, had Taylor been allowed to wipe out Banks and

Porter, that the election of 1864 might have elected

McClellan, leading to a peace treaty. The odds against this theory are

almost prohibitive.

In the end, a military campaign conceived for non-military reasons

ended up hurting other Union campaigns that were far more important to

prosecution of the war. The Red River campaign is "a study in how

partisan politics, economic need and personal profit can determine

military policy and operations. It is also a story of inept military

operations in a tactically useless theater of operations, an operation

in which the Union Army was nearly annihilated and the Union River Navy

was almost sunk or captured intact. A side effect was to delay the end

of the war. Blunder does not begin to connote the foolishness of this

campaign. It was a short operation, lasting from only March 12 to May

20, but wound up being one of the most destructive of the entire war."

Ironically, the Red River Campaign had several beneficial

aftereffects: army and navy operations became truly "combined"

under a single commander instead of relying on cooperation between two

equally egotistical commanders. Bailey’s dam was a brilliant adaptation

of logging industry techniques. And, for the first time, Capt. Thomas O.

Selfridge, Jr., aimed a gun using a periscope invented a few days

earlier on board his vessel that succeeded in killing a Confederate

general and staff. Selfridge, who commanded the U. S. S. Monitor for

four days, served with distinction throughout the war and ended up an

admiral in charge of the Pacific Fleet, is included, primarily because

one of my Chicago law partners was reputedly a descendant of his!

Finally, and most importantly, the navy learned not to take large

vessels into tight quarters and instead developed vessels that evolved

into the famous Swift Boats used in the Vietnam war. [One Damned

Blunder, pages 174-75].

A question and answer session, followed by well-earned applause,

ended the evening.

# # #

Last changed: 09/09/13

Home

About News

Newsletters

Calendar

Memories

Links Join

|