|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| "To you, Sons of Confederate Veterans, we commit the vindication of the cause for which we fought. To your strength will be given the defense of the Confederate soldier's good name, the guardianship of his history, the emulation of his virtues, the perpetuation of those principles which he loved and which you love also, and those ideals which made him glorious and which you also cherish. Remember, it is your duty to see that the true history of the South is preserved to future generations." |

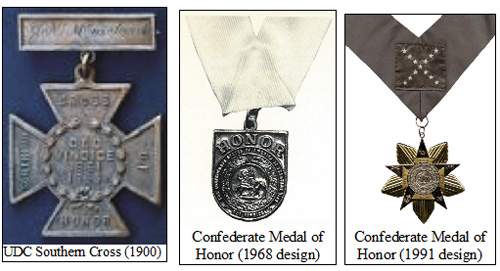

However, nothing was done about recreating a Confederate Medal of Honor until August 16, 1968, when the SCV passed a resolution at its annual convention to reestablish the medal. To avoid controversy, there had to be certified proof that each recipient performed "above and beyond the call of duty, at the peril of one’s life" (Requirements similar to those for the United States Medal of Honor after 1917).

Even then, it was not until Memorial Day 1977 that the first medal was actually awarded, as Krasner noted in his introduction. The silver-and-bronze medal is a 10-pointed star bearing the Great Seal of the Confederate States and the words "Honor Duty Valor Devotion." Krasner then read 25 of the 51 citations. [Only 8 citations and pictures of 4 medals could fit in the print Newsletter, but your editor will try to put the other 17 citations in an addendum to the web-site.]

Private Samuel Davis, Coleman’s Scouts, Pulaski, Tennessee,

November 27, 1863

“Captured and found to possess documents detailing the plans

and troop dispositions of the enemy, Private Davis refused to identify

his informants in exchange for his life. Summarily tried and convicted

as a spy before a military courts-martial, Private Davis was sentenced

to death by hanging. While imprisoned, he was offered his life if he but

cooperated with the enemy, but again, Private Davis steadfastly rejected

his captors. On the day of execution, moments before the rope was placed

around his neck, Private Davis heard one last offer from an enemy agent

who informed him that “It was not too late yet.” Turning to his

executioner, he answered, “Do you suppose I would betray a friend? No

sir, I would die a thousand deaths first.”

Sergeant Richard Rowland Kirkland, 2nd South Carolina

Infantry, Fredericksburg, Virginia, December 14, 1862 (The “Angel of

Marye’s Heights)

“On

the day after the battle, unable to endure any longer the pitiful cries

of the wounded for water, Sergeant Kirkland vaulted the stone wall armed

only with full canteens in an effort to relieve the suffering of the

maimed. Perilously exposed yet miraculously unscathed by the muskets of

the enemy who mistook his intentions, Sergeant Kirkland commenced his

mission of mercy to the wounded, arranging knapsacks as pillows,

straightening broken limbs, covering freezing bodies with overcoats, and

always quenching desperate thirsts with life-giving water, for an hour

and a half he went about his humane work as both sides held their fire

in admiration, until all the wounded in that part of the field were

tended.”

“On

the day after the battle, unable to endure any longer the pitiful cries

of the wounded for water, Sergeant Kirkland vaulted the stone wall armed

only with full canteens in an effort to relieve the suffering of the

maimed. Perilously exposed yet miraculously unscathed by the muskets of

the enemy who mistook his intentions, Sergeant Kirkland commenced his

mission of mercy to the wounded, arranging knapsacks as pillows,

straightening broken limbs, covering freezing bodies with overcoats, and

always quenching desperate thirsts with life-giving water, for an hour

and a half he went about his humane work as both sides held their fire

in admiration, until all the wounded in that part of the field were

tended.”

Private Wilson J. Barbee, 1st Texas Infantry, Gettysburg,

Pennsylvania, July 2, 1863

“Although detailed as a courier to the division commander, Private

Barbee joined his regiment near Devil’s Den during the hottest part of

the engagement. Eager for action, Private Barbee climbed a high,

prominent rock and with wounded comrades passing him loaded muskets,

opened fire on the enemy. Although dangerously exposed to a storm of

enemy fire by his defiant, erect stance on the rock, Private Barbee

continued to discharge is weapon until knocked from his position by a

bullet to his right leg. Despite his wound, he promptly reclimbed the

rock and continued to fire at the enemy. Moments later, a bullet to the

left leg tumbled him from his perch, but again he crawled to the top of

the rock and fought on. After having fired more than two dozen rounds, a

third, serious wound to his body knocked Private Barbee into a crevice

where, despite his cries for aid so that he might continue the fight, he

lay trapped on his back until freed at the battle’s end. His reckless

example of valor solidified the battle line during the height of the

fighting and remained an inspiration to his comrades for the rest of

their lives.”

Captain Samuel Jones Ridley, 1st Mississippi Artillery, Bailey’s Creek, Mississippi, May 16, 1863

"Riding

hard to bring the last reserves to the field after the Confederate line

had been broken on the far left, Captain Ridley personally guided the

42nd Georgia Volunteers and two guns of his battery to a position where

they could enfilade the advance of the enemy. Although badly outnumbered

Captain Ridley directed and maintained a heavy fire into the attacking

enemy line, thwarting the momentum of the assault that threatened to

envelop the Confederate left flank. Seeing all infantry support driven

from the field and realizing that many of his men lay killed or wounded,

Captain Ridley nevertheless joined the survivors of one gun crew to keep

the cannon firing. Ignoring his own safety despite horrific casualties

and realizing that his own position was in danger of being overrun, he

continued to serve the gun until he alone stood at the cannon's mouth.

When last seen alive, he was still at his post, dealing destruction to

the enemy and unwilling unto death to yield his ground." [Editor’s note:

the North called this the Battle of Champion Hill.]

"Riding

hard to bring the last reserves to the field after the Confederate line

had been broken on the far left, Captain Ridley personally guided the

42nd Georgia Volunteers and two guns of his battery to a position where

they could enfilade the advance of the enemy. Although badly outnumbered

Captain Ridley directed and maintained a heavy fire into the attacking

enemy line, thwarting the momentum of the assault that threatened to

envelop the Confederate left flank. Seeing all infantry support driven

from the field and realizing that many of his men lay killed or wounded,

Captain Ridley nevertheless joined the survivors of one gun crew to keep

the cannon firing. Ignoring his own safety despite horrific casualties

and realizing that his own position was in danger of being overrun, he

continued to serve the gun until he alone stood at the cannon's mouth.

When last seen alive, he was still at his post, dealing destruction to

the enemy and unwilling unto death to yield his ground." [Editor’s note:

the North called this the Battle of Champion Hill.]

1st Lt. Richard William Dowling, 1st Texas Heavy Artillery, Sabine Pass, Texas, September 8, 1863

"Attacked

by four enemy gunboats, Lieutenant Dowling ordered his 42 men to hold

their fire until the gunboats reached a premeasured range. At his

command and in spite of the hot and furious assault upon their position,

Lieutenant Dowling’s men answered with an incredibly accurate fire.

After 45 minutes of action in which 137 projectiles were fired from six

guns, two of which were soon put out of action, Lieutenant Dowling’s

command inflicted more than 400 casualties and compelled the surrender

of the USS Clifton and Sachem, together with 350

prisoners, while themselves sustaining no serious injuries. By his

intrepid leadership and defense at Sabine Pass, Lieutenant Dowling

thwarted an amphibious invasion of Texas by 5,000 infantry on an armada

of twenty-two transports and four gun ships."

"Attacked

by four enemy gunboats, Lieutenant Dowling ordered his 42 men to hold

their fire until the gunboats reached a premeasured range. At his

command and in spite of the hot and furious assault upon their position,

Lieutenant Dowling’s men answered with an incredibly accurate fire.

After 45 minutes of action in which 137 projectiles were fired from six

guns, two of which were soon put out of action, Lieutenant Dowling’s

command inflicted more than 400 casualties and compelled the surrender

of the USS Clifton and Sachem, together with 350

prisoners, while themselves sustaining no serious injuries. By his

intrepid leadership and defense at Sabine Pass, Lieutenant Dowling

thwarted an amphibious invasion of Texas by 5,000 infantry on an armada

of twenty-two transports and four gun ships."

Private William Thomas Overby, 43rd Battalion, Virginia Cavalry, Front Royal, Virginia, September 23, 1864

"Captured with five others in a skirmish outside Front Royal, Private Overby and his companions, instead of receiving the humane treatment accorded prisoners of war, were ordered to be executed. Reviled and beaten by his captors, Private Overby could only watch as three of his fellow prisoners were wrenched away, dragged through the streets and summarily shot. Private Overby nevertheless remained erect and defiant. Despite a noose around his neck, he refused to give his executioners vital information that could compromise his battalion, even in exchange for his life; instead, with his last words, issued a dark prophecy of revenge."

Private Albury V. Hancock, 19th Mississippi Infantry, Spotsylvania Court House, May 12, 1864

"During the desperate struggle for he salient, with much of the fighting hand-to-hand, and with the fate of the army hanging in the balance, Private Hancock voluntarily left the cover of the traverses and braved a terrific storm of musketry--perhaps some of the most intense of the war–to bring badly needed ammunition to his exhausted comrades in arms. Although detailed as a courier to the brigade commander, he repeatedly risked his life to cross the bullet-swept terrain in the all day fight in the rain, promptly returning each time with more cartridges for the men in the works with little concern for his own safety. Private Hancock’s unselfish action despite witnessing the death or wounding of so many others in the same attempt, was valor of the highest order, and marked him for special notice from the brigadier general commanding."

Captain John Singleton Mosby, Mosby’s Regulars, Raid on Fairfax

Courthouse,

March 8-9, 1863

With

only twenty-nine men, Captain Mosby stealthily entered the enemy’s line

undetected and under cover of the night and made his way to the

headquarters of the commanding general. After ordering telegraph lines

cut and all horses, arms and ammunition seized, Captain Mosby entered a

private residence and captured the brigadier general commanding. With

his raid complete, his captured stores and prisoners guarded and all his

men accounted for, Captain Mosby, now more than ten miles behind enemy

lines, led his men south and then abruptly west to confuse pursuers.

Again employing stealth and brazen audacity, Captain Mosby guided his

column into the night past numerous enemy lines. As a result of his

daring raid, Captain Mosby captured one brigadier general, two captains,

thirty other prisoners, fifty-eight horses and numerous arms and

equipment, all without firing a shot. In this singular action that so

typified his movements throughout the war, Captain Mosby instilled a

fearsome respect among his foes while engendering a lasting admiration

from his comrades in arms."

With

only twenty-nine men, Captain Mosby stealthily entered the enemy’s line

undetected and under cover of the night and made his way to the

headquarters of the commanding general. After ordering telegraph lines

cut and all horses, arms and ammunition seized, Captain Mosby entered a

private residence and captured the brigadier general commanding. With

his raid complete, his captured stores and prisoners guarded and all his

men accounted for, Captain Mosby, now more than ten miles behind enemy

lines, led his men south and then abruptly west to confuse pursuers.

Again employing stealth and brazen audacity, Captain Mosby guided his

column into the night past numerous enemy lines. As a result of his

daring raid, Captain Mosby captured one brigadier general, two captains,

thirty other prisoners, fifty-eight horses and numerous arms and

equipment, all without firing a shot. In this singular action that so

typified his movements throughout the war, Captain Mosby instilled a

fearsome respect among his foes while engendering a lasting admiration

from his comrades in arms."

Last changed: 10/01/14