Volume

27, No. 3 – March 2014

Volume 27, No. 3

Editor: Stephen L. Seftenberg

Website:

www.CivilWarRoundTablePalmBeach.org

March 12, 2014 Program

The Round Table is honored to have the distinguished lecturer and

nationally renowned historian, James "Bud" Robertson

speaking at the March meeting. I have had the privilege of hearing Dr.

Robertson, and it is not to be missed. His reputation extends well

beyond the campus of Virginia Tech. Dr. Robertson is the author of more

than 20 books and has received every major award in Civil War history.

His highly acclaimed biography of Stonewall Jackson, Gods and

Generals, is considered the definitive biography of Jackson. The

movie "Gods and Generals" was based on that book

with Dr. Robertson serving as historical consultant. His topic will be

the "Untold Civil War."

February 11, 2014 Program

Lawrence Lee Hewitt: "Civil War Myths, Mistakes and Fabrications "

Lawrence

Lee Hewitt (B.A. University of Kentucky, Ph.D. Louisiana State

University, professor emeritus Southeastern Louisiana University)has

received awards from the Civil War Roundtables of New Orleans and

Chicago and the President’s Award for Excellence in Research,

Southeastern Louisiana University’s highest award. Among his many

publications are Port Hudson, Confederate Bastion on the Mississippi,

The Confederate High Command & Related Topics, Leadership During the

Civil War, and 200 Years a Nation. Lawrence

Lee Hewitt (B.A. University of Kentucky, Ph.D. Louisiana State

University, professor emeritus Southeastern Louisiana University)has

received awards from the Civil War Roundtables of New Orleans and

Chicago and the President’s Award for Excellence in Research,

Southeastern Louisiana University’s highest award. Among his many

publications are Port Hudson, Confederate Bastion on the Mississippi,

The Confederate High Command & Related Topics, Leadership During the

Civil War, and 200 Years a Nation.

Hewitt began by defining myth as something that people

wrongly believe to be true. The mythmakers are either supposed

eyewitnesses or historians writing after the fact. It is the job of the

latter to ferret out and expose the mistakes or lies of the former, but

sometimes they find that a dubious story is just too good not to retell.

Sometimes the historian is mislead by the available evidence. Even the

best historian can make mistakes. Worse, some historians and even

eyewitnesses fabricate stories for various reasons. Joseph Goebbels

observed that if a lie is repeated often enough, it becomes the “truth.”

He had nothing on some Civil War writers.

Honest Mistakes

Ed Bearss and Tim Smith, both highly respected Civil War authors,

have mistakenly perpetuated a not so trivial mistake. For the death of

Lloyd Tilghman at Champion Hill, both cite an 1893 "eyewitness" account

by "F.W.M." in the magazine Confederate Veteran. Veterans often

challenge accounts of others, and veteran E. T. Eggleston responded in

the very next issue that "F.W.M." was 1st Lieutenant F. W. Merrin, who

had been ordered to the rear nearly four hours before Tilghman was

killed, so Merrin could not have been an "eyewitness." Bearss and Smith

never changed their story. I guess they missed Eggleston’s

response.

Even the Official Records can err. They state that Brigadier General

John Roane accompanied Major General Earl Van Dorn from Arkansas

to Mississippi in the spring of 1862, and participated in the siege of

Corinth. The facts are that Roane was left charge in Arkansas and was

never at Corinth. Bruce Aliardice got it right in More Confederate

Generals, the first of us to do so.

Fabrications

Nearly

twenty years ago Marshal Krolick (a member of both Chicago and Palm

Beach County Roundtables) asked me to find the source for a conversation

between Robert E. Lee and Jeb Stuart on the afternoon of July 2, 1863. I

was unaware that he was testing me. I failed to find it in any of the

accounts left by Lee's staff officers, but in John Thomason's Jeb

Stuart, published in 1934, Thomason wrote," ‘Well, General Stuart,

you are here at last!' says Lee, austerely. "Douglas Southall Freeman,

in Lee's Lieutenants, carefully stated "The tradition is that Lee

said, 'Well, General Stuart, you are here at last," omitting

"austerely.' In 1957, Burke Davis, in Jeb Stuart, added: "Lee

reddened at sight of Stuart and raised his arm as if he Nearly

twenty years ago Marshal Krolick (a member of both Chicago and Palm

Beach County Roundtables) asked me to find the source for a conversation

between Robert E. Lee and Jeb Stuart on the afternoon of July 2, 1863. I

was unaware that he was testing me. I failed to find it in any of the

accounts left by Lee's staff officers, but in John Thomason's Jeb

Stuart, published in 1934, Thomason wrote," ‘Well, General Stuart,

you are here at last!' says Lee, austerely. "Douglas Southall Freeman,

in Lee's Lieutenants, carefully stated "The tradition is that Lee

said, 'Well, General Stuart, you are here at last," omitting

"austerely.' In 1957, Burke Davis, in Jeb Stuart, added: "Lee

reddened at sight of Stuart and raised his arm as if he would strike him. ‘General Stuart, where have you been?’" Davis's

fabrication failed to catch on, while Thomason's fabrication lives on,

even being used in the movie Gettysburg. The truth is no one will

ever know what Lee said when he greeted Stuart because no one else was

present and neither Lee nor Stuart left an account of the meeting. Now

consider for a moment that at the time Stuart entered Lee's tent the

Union Army of the Potomac was on the ropes and Lee was sure

he was about to deliver a knockout blow. Wasn't Stuart’s arrival all

that Lee could have wished for? Isn't it possible that Lee did raise his

arms when Stuart entered, not to strike him but to give him a big hug,

perhaps even saying "Well, General Stuart, you are here at last!"

would strike him. ‘General Stuart, where have you been?’" Davis's

fabrication failed to catch on, while Thomason's fabrication lives on,

even being used in the movie Gettysburg. The truth is no one will

ever know what Lee said when he greeted Stuart because no one else was

present and neither Lee nor Stuart left an account of the meeting. Now

consider for a moment that at the time Stuart entered Lee's tent the

Union Army of the Potomac was on the ropes and Lee was sure

he was about to deliver a knockout blow. Wasn't Stuart’s arrival all

that Lee could have wished for? Isn't it possible that Lee did raise his

arms when Stuart entered, not to strike him but to give him a big hug,

perhaps even saying "Well, General Stuart, you are here at last!"

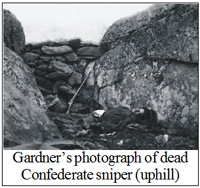

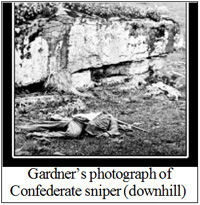

Part of the historian's job is to give their best guess in the

absence of definitive evidence and make it clear to the reader that it

is only an opinion. lt is not unusual for such assumptions to be

challenged. Alexander Gardner's "Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter" is

one of the most famous photographs of the Civil War. In 1961, Frederic

Ray, in Civil War Times Magazine, demonstrated that the body of

the sharpshooter had also been photographed in a second location, 70

yards away. In 1975, William Frassanito, in Gettysburg: A Journey in

Time, erroneously stated that Ray had claimed that Gardner and his

two assistants had moved the body up the hill to stage a better

composition using the boulders and rock wall in Devil's Den. In 1995

Frassanito, in Early Photography at Gettysburg, acknowledged that

Ray never claimed that the body had been moved up the hill and admitted

that he couldn't prove which way the body had been moved. But the

National Park Service had already accepted his 1975 claim, labeled the

uphill sharpshooter photograph as a fake, and continues to do so. In an

article published in 1998, James Groves claimed that the first,

unstaged, shot was of the body up the hill. Unlike Frassanito, Groves

provided an eyewitness account of the death of the sharpshooter and gave

two reasons why Gardner would have wanted to move the body down the

hill.

I agree with Groves that the uphill sharpshooter image is the

unstaged one. My evidence for this is his mangled right leg.

According to Dr. Edgardo Rodriguez, who specializes in complex trauma to

the lower extremity, only two possibilities explain the position of the

sharpshooter's pelvis, right leg, and right foot in the photographs

taken down the hill: tibial fracture or knee disarticulation and

dislocation. Nothing visible on the pants leg indicate that a projectile

caused the injury; nor could it have been sustained by being blown onto

his back by the concussion from an exploding artillery shell. For all

the controversy surrounding the photographs, two things are certain. The

subject was killed, and his right leg sustained one of two possible

injuries, neither of which would have proved fatal. Also, no external

wounds are visible. Neither concussion nor a fatal shot in the back

could have caused his leg injury. But the concussion that killed him in

the Devil’s Den probably also caused at least one large stone to topple

from the wall onto his lower right leg. As the photographer set up the

camera his assistants removed any stones from the body. That was the

only "staging" that occurred. For those who doubt my conclusion,

consider this: There are no photographs of the body in a third location

and no other photographer or artist captured the image uphill at the

wall. If Gardner had staged the shot at the wall would he have left the

body there for his competitors to copy?

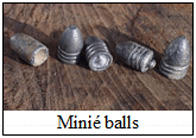

Misunderstandings

Smoothbore shoulder weapons had an effective range of 50 yards;

rifles prior to 1855 had an effective range of 200 yards. In an 1861

Springfield rifled-musket, the minié ball was accurate at 400 yards and

could kill at 1000 yards; it was also faster to load than the pre 1855

rifles. Foremost among the historians who understood the significance of

the minié ball as well as the rifled-musket and who argue that they made

earlier tactics obsolete are the late Grady McWhiney and Perry Jamieson,

who published Attack and Die in 1982. The title says it all. Massed

assaults by infantry were likely to be both costly and unsuccessful

because of the increased range of the defender's weapons. Two

historians, however, argue that the tactics used by Civil War generals

were not outdated because of how these longer ranged weapons were

actually used. The only American historian to seriously consider the

topic is Earl Hess, who published The Rifle Musket in Civil War Combat:

Reality and Myth in 2008. Hess argued that the rifle's potential to

alter the outcome of a battle at a distance was nullified for a variety

of reasons. Possibly the most significant was that defenders were seldom

ordered to begin firing until the enemy was within 200 yards, and with

good reason. One thing Hess mentioned (and other historians seldom

consider) is how many rounds a soldier carried into battle (40-60) and

how many of those could be fired before the gunpowder fouled the rifle

(approximately 20 for Confederates and maybe 40 for Union soldiers

having cleaner bullets). Cleaning a fouled rifle required at least

partial dismantling and was easier with water. What soldier would want

to be caught with a useless rifle when the enemy is close?

Much has been written about Civil War commanders who fought the war

with tactics made obsolete by the rifle. Historians still condemn their

stupidity, but few historians have realized what Jefferson Davis did in

1855. It was not the rifled barrel that was revolutionary, it was

the minié ball.

Was the Trans-Mississippi the "Junkyard of the

Confederate Army"?

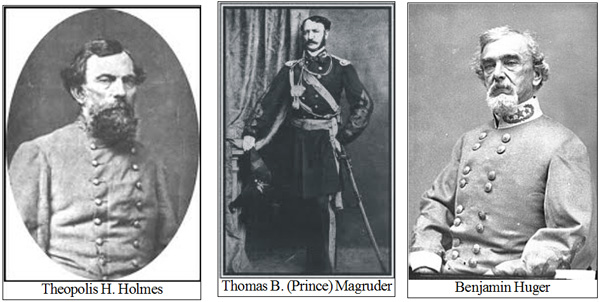

"Huey, Dewey and Louie?"

The transfers to the West of the three Generals pictured above

supposedly supports Albert Castel’s reference to the Trans-Mississippi

theater as "the junkyard of the Confederate Army," where those found

wanting in the East were sent to limit the harm they could do. William

C. Davis amplified this dumping ground theme when he wrote that "in the

summer of 1862 President Jefferson Davis began a war-long policy of

sending discredited or incompetent generals [West] to command or using

it to shelve personal favorites who had become too controversial to keep

in the East." Craig Symonds also weighed in: "When Robert E. Lee took

over the command of the Army in Virginia... he measured his subordinate

commanders by a simple standard: success. When a particular officer

proved himself in combat, Lee promoted him; when he did not, Lee did not

demote him. . ., instead he contrived to have him sent to another

theater, generally to the West. Without saying so, Lee used the West

or actually any theater outside Virginia as a dumping ground for

officers he did not want around him any more." Let’s check the

record:

Thomas B. ("Prince") Magruder was ordered to the

Trans-Mississippi in May 1862, before Lee took command of the

army. His transfer was delayed so he could face a courts-martial for

drunkenness during the Seven Days' Battles in Richmond. During May, June

and July, while Magruder remained in Virginia, Major General

Hindman, commander of the Trans-Mississippi north of the Red River, so

alienated the politicians there that Davis promised to replace him. When

Magruder could not take over promptly, Davis sent the only officer

available who outranked Hindrnan: Theopolis H. Holmes. Lee had

nothing to do with the departure of either Magruder or Holmes! Before

the start of the Seven Days' Battles, Lee had urged Davis to send

Benjamin Huger to South Carolina to replace the unpopular and

suspected traitor John Pemberton. Longstreet's lies about Huger's

performance during the Seven Days' caused Huger instead to be

transferred to the Texas coast, where his ordnance talents were

desperately needed.

The

record does not bear out the slur: A total of 73 Confederate

generals served in the Trans-Mississippi. Of these, 38 served only West

of the Mississippi; 4 were transferred East; 7 sent West were later

transferred back East; 13 were either requested by Kirby Smith,

requested the transfer themselves, or obtained a leave of absence on

their own to go there; 3 were sent only because of disabling wounds; and

1 was sent because his brigade had been captured at Vicksburg but

paroled West of the Mississippi. A total of 66 (90.4%) could not

be considered to have been dumped there. Among the 7 remaining, John G.

Walker was transferred from the Army of Northern Virginia over Lee's

written objection; and William Preston had been transferred to the

Trans-Mississippi by Bragg for disloyalty rather than incompetence. Even

if the remaining 5 were the worst generals in the Confederacy it would

not make the Trans-Mississippi a dumping ground. And they were not:

Sibley started there and Polk, Northrop, and Floyd never served West of

the Mississippi. The fifth one Hewitt left for us to discover. The

record does not bear out the slur: A total of 73 Confederate

generals served in the Trans-Mississippi. Of these, 38 served only West

of the Mississippi; 4 were transferred East; 7 sent West were later

transferred back East; 13 were either requested by Kirby Smith,

requested the transfer themselves, or obtained a leave of absence on

their own to go there; 3 were sent only because of disabling wounds; and

1 was sent because his brigade had been captured at Vicksburg but

paroled West of the Mississippi. A total of 66 (90.4%) could not

be considered to have been dumped there. Among the 7 remaining, John G.

Walker was transferred from the Army of Northern Virginia over Lee's

written objection; and William Preston had been transferred to the

Trans-Mississippi by Bragg for disloyalty rather than incompetence. Even

if the remaining 5 were the worst generals in the Confederacy it would

not make the Trans-Mississippi a dumping ground. And they were not:

Sibley started there and Polk, Northrop, and Floyd never served West of

the Mississippi. The fifth one Hewitt left for us to discover.

As for Lee, he was no different than any other senior commander.

Bragg got rid of several generals for multiple reasons, and Kirby Smith

even got rid of Richard Taylor, his best subordinate, for personal

reasons. Nor did Lee always got what he wanted. I've already mentioned

Hill and Walker. Lee would have preferred to have kept Richard Taylor

and Wade Hampton but he knew better than to ask, and Davis forced Lee to

relieve Jubal Early. Lastly, Lee on one occasion even used Virginia as a

dumping ground, transferring Richard Ewell to the Department of

Richmond.

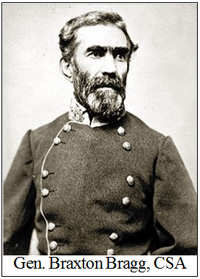

Braxton Bragg was, and remains, an easy target for

fabrications. The most ridiculing story about Bragg allegedly occurred

prior to the Mexican War when 1st Lt. Bragg found himself acting as both

company commander and post quartermaster. "As commander of the company

he made a requisition upon the quartermaster [that is, himself] for

something he wanted. As quartermaster he declined to fill the

requisition, and endorsed on the back of it his reasons for so doing. As

company commander he responded to this, urging that his requisition

called for nothing but what he was entitled to, and that it was the duty

of the quartermaster to fill it. As quartermaster he still persisted

that he was right. In this condition of affairs Bragg referred the whole

matter to the commanding officer of the post. The latter exclaimed: "My

God, Mr. Bragg, you have quarreled with every officer in the army, and

now you are quarreling with yourself!" The source for this is the

Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant, published in 1885. The story went

undisputed until 2011, when Samuel Martin began his biography of Bragg

with Grant's story, and concluded, correctly: "Grant's humorous tale is

obviously false."

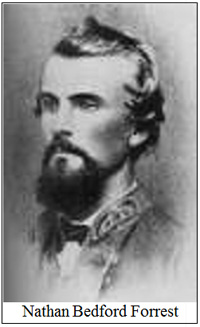

One of the most harmful fabricated Bragg tales regards his

relationship with Nathan Bedford Forrest. These are the facts: In

June of 1862, Beauregard persuaded Colonel Forrest to give up his

regiment and go to East Tennessee to take command of the cavalry in the

vicinity of Chattanooga, hinting that he would be promoted to Brigadier

General if he did so. Bragg was not involved. By the time Forrest was

promoted to brigadier in July, Bragg had replaced Beauregard and was

moving toward East Tennessee himself, where Bragg welcomed Forrest as

commander of all his cavalry. In September during the invasion of

Kentucky, Forrest's horse fell and then rolled over on him, dislocating

his right shoulder. Confined to a buggy and unable to keep up with his

command, Bragg ordered him to Murfreesboro with a small contingent.

There he was to recruit additional regiments and harass the enemy. There

was no animosity on the part of either of them regarding this assignment

because Bragg had allowed Forrest to save face. When Bragg organized the

Army of Tennessee in November, he placed Joseph Wheeler in command of

all his cavalry except for the brigades of Forrest and John Hunt Morgan.

This was done because Forrest and Morgan both outranked Wheeler, and

because Forrest and Morgan had demonstrated greater ability at

conducting raids than in gathering intelligence. Forrest preferred the

freedom this assignment allowed him so there was no cause for hard

feelings on his part. In February 1863, while Forrest was on leave,

Wheeler borrowed 800 of Forrest's men for a raid against Dover,

Tennessee. When Forrest learned of this he managed to join his men just

before Wheeler ordered the town attacked. Forrest objected to Wheeler's

plan, but Wheeler, now a major general, proceeded. It turned out to be a

disaster and Forrest refused to ever serve under Wheeler again. The

Bragg of myth would have sacked Forrest for insubordination; the real

Bragg honored Forrest's request by transferring Forrest--and his

brigade---to Major General Earl Van Dorn's cavalry corps. Following Van

Dorn's assassination by a jealous husband, Bragg offered to have Forrest

promoted to major general but Forrest declined; Bragg gave him Van

Dorn's command anyway. In late September, while on leave, Forrest

learned that Bragg had assigned some of his men to Wheeler. When Forrest

protested, Bragg assured him that the men would be returned to his

command when he returned from his leave and Forrest acquiesced.

Every

modern biography of Forrest and of Bragg contains the following dramatic

but false story: Sometime during the fall of 1863 Forrest stormed into

Bragg's tent. Bragg rose and extended his hand: "Refusing to take the

proffered hand, and standing stiff and erect before Bragg, Forrest said:

"I am not here to pass civilities or compliments with you, but on other

business. You commenced your cowardly and contemptible persecution of me

soon after the battle of Shiloh, and you have kept it up ever since. You

did it because I reported to Richmond facts, while you reported damned

lies. You robbed me of my command in Kentucky, that I armed and equipped

from the enemies of our country, and gave it to one of your favorites.

In a spirit of revenge and spite, because I would not fawn upon you as

others did, you drove me into West Tennessee in the winter of 1862, with

a second brigade I had organized, with improper arms and without

sufficient ammunition, although 1 had made repeated applications for the

same. You did it to ruin me and my career. When in spite of all this I

returned with my command, well equipped by captures, you began again

your work of spite and persecution, and have kept it up; and now this

second brigade, organized and equipped without thanks to you or the

government, a brigade which has won a reputation for successful fighting

second to none in the army, taking advantage of your position as the

commanding general in order to further humiliate me, you have taken

these brave men from me. I have stood your meanness as long as I intend

to. I say to you that if you ever again try to interfere with me or

cross my path it will be at the peril of your life." Forrest is then

said to have stormed out. And Bragg did nothing! Every

modern biography of Forrest and of Bragg contains the following dramatic

but false story: Sometime during the fall of 1863 Forrest stormed into

Bragg's tent. Bragg rose and extended his hand: "Refusing to take the

proffered hand, and standing stiff and erect before Bragg, Forrest said:

"I am not here to pass civilities or compliments with you, but on other

business. You commenced your cowardly and contemptible persecution of me

soon after the battle of Shiloh, and you have kept it up ever since. You

did it because I reported to Richmond facts, while you reported damned

lies. You robbed me of my command in Kentucky, that I armed and equipped

from the enemies of our country, and gave it to one of your favorites.

In a spirit of revenge and spite, because I would not fawn upon you as

others did, you drove me into West Tennessee in the winter of 1862, with

a second brigade I had organized, with improper arms and without

sufficient ammunition, although 1 had made repeated applications for the

same. You did it to ruin me and my career. When in spite of all this I

returned with my command, well equipped by captures, you began again

your work of spite and persecution, and have kept it up; and now this

second brigade, organized and equipped without thanks to you or the

government, a brigade which has won a reputation for successful fighting

second to none in the army, taking advantage of your position as the

commanding general in order to further humiliate me, you have taken

these brave men from me. I have stood your meanness as long as I intend

to. I say to you that if you ever again try to interfere with me or

cross my path it will be at the peril of your life." Forrest is then

said to have stormed out. And Bragg did nothing!

The first to question the veracity of this account was Judith

Hallock, who completed McWhiney's biography of Bragg in 1991. Jim Ogden,

historian at the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park,

agreed with Hallock and so indicated to Dave Powell a few years ago. The

best published account of what really happened appears in Powell’s

Failure in the Saddle (2010). Powell is to be commended for not only

omitting the story from his text (because he believed it false), but

also for giving the reasons for his conclusion in an appendix. In some

respects, this story resembles the imagined incident

between Lee and Stuart at Gettysburg. Neither Bragg nor Forrest ever

mentioned the incident, nor does it appear in Jordan and Pryor's The

Campaigns of Lieut. Gen. N. B. Forrest (1868), which was basically

an autobiography. The story originated with Dr. James Cowan, Forrest's

chief surgeon, in Wyeth's Life of General Nathan Bedford Forrest (1899).

Cowan claimed to have followed Forrest into Bragg's tent, making him the

only eyewitness, and the only one of the three still alive when his tale

was printed. Historians wishing to repeat Cowan's good story had no

problem altering the doctor's time line to make it correspond with

undisputable facts. For what actually happened, I refer you to Powell's

account, which concludes: "Perhaps the confrontation unfolded when and

as described by Dr. Cowan. Or, perhaps the infamous confrontation was

simply a war story spun in old age by Forrest's former surgeon as he

remembered fondly his revered kinsman and commander. Unless additional

credible contemporary accounts surface, it is impossible to know with

certainty whether this incident really took place."

An "additional credible contemporary account" exists: On December 8,

1863, between eight and eleven weeks after the alleged encounter

and when he was no longer under Bragg's command, Forrest wrote Bragg a

detailed letter. Not only is there no mention of any animosity on

Forrest's part, he concludes: "I am not only willing, hut desirous,

general, of rendering the country all the service possible in the

occupancy and defense of West Tennessee; also to get out from here all

the supplies I can for the subsistence of your army. If you can aid me

in the services of a general officer or the procurement of arms I shall

be thankful, and in turn use every exertion to send to you the absentees

from your ranks and supplies, &c., for your troops. I am, general, very

respectfully, your obedient servant, N. B. Forrest, Brigadier-General,

Commanding." When Forrest wrote this letter he was unaware that his

appointment to major general, which Bragg had been pursuing since Van

Dorn's death, had been made four days earlier, so he is not retracting

anything in gratitude. There was never any animosity between the

two men.

Bragg was heavily criticized for retreating after winning the Battle

of Perryville, but he acted prudently because he knew that a powerful

Federal army was bearing down on him and victory would have turned into

defeat had he tarried. It was the Duke of Wellington who said that a

great general has to know when he should retreat and to have the courage

to retreat, knowing he will be criticized for it. Finally, the story

that Bragg had a soldier executed for shooting a chicken is a calumny:

the soldier was executed for shooting at a chicken but killing a fellow

soldier instead.

Admittedly, the myths, mistakes and fabrications I have recounted

vary in significance regarding our understanding of the Civil War today.

However, one of the most significant fabrications relates to the number

of fatalities. In a presentation to the Chicago Civil War Round Table in

January 2011, I claimed that thousands of Civil War soldiers who died in

service were officially listed wrongly as having deserted.

Curt Carison asked me how one might prove my point. I said that one

could start by totaling up the difference between the number of men

reported missing by their side and those captured by the enemy. J. David

Hacker, a demographic and social historian, found a better way. In "A

Census-Based Count of the Civil War

Dead," he concluded that the 1860 and 1870 censuses demonstrated that

instead of the accepted figure of 620,000 deaths, at least 752,000 and

possibly even 851,000 died. But he couldn't explain how such a

discrepancy could exist, as he was unaware of the dead who were reported

as deserters. Two incidents illustrate my point: at the Battle of the

Crater, a Colonel and a 2nd Lieutenant were reported as "presumed dead,"

while hundreds of enlisted men who were also blown to pieces there were

reported as "presumed deserted." And at Port Hudson, when so many black

Union soldiers were killed trying to surrender, the official Union

report listed 85% of an entire company as "deserted." We may speculate

upon the motives for this "erroneous" reporting, but the truth may lie

in the terrible time the widows of these alleged "deserters" had in

getting their widow’s pensions from a penny-pinching government or

discrimination towards enlisted deaths, or both.

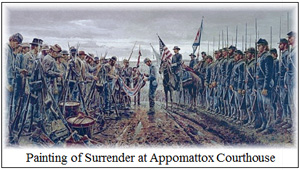

Not All Fabrications Have Bad Motives

Hewitt

said, of all his mentor, Prof. T. Harry Williams' lectures, his most

popular, and his favorite, was the final lecture for each Civil War

class. He brought many in the audience to tears as he read a passage

from a 1901 article by Joshua L. Chamberlain, who commanded the Union

soldiers at the surrender at Appomattox Courthouse: "At such a time and

under such conditions I thought it eminently fitting to show some token

of our feeling, and I therefore instructed my subordinate officers to

come to the position of [Carry Arms] 'salute' in the manual of arms as

each body of the Confederates passed before us... I may best describe it

as a marching salute in review. When General Gordon came opposite me I

had the bugle blown and the entire line came to 'attention,' preparatory

to executing this movement of the manual successively and by regiments

as Gordon's columns should pass before our front, each in turn. The

General was riding in advance of his troops, his chin drooped to his

breast, downhearted and dejected in appearance almost beyond

description. At the sound of that machine-like snap of arms, however,

General Gordon started, caught in a moment its significance, and

instantly assumed the finest attitude of a soldier. He wheeled his horse

facing me, touching him gently with the spur, so that the animal

slightly reared, and as he wheeled, horse and rider made one motion, the

horse's head swung down with a graceful bow, and General Gordon dropped

his sword point to his toe in salutation. . . .General Gordon sent back

orders to the rear that his own troops take the same position of the

manual in the march past as did our line. That was done, and a truly

imposing sight was the mutual salutation and farewell." Hewitt

said, of all his mentor, Prof. T. Harry Williams' lectures, his most

popular, and his favorite, was the final lecture for each Civil War

class. He brought many in the audience to tears as he read a passage

from a 1901 article by Joshua L. Chamberlain, who commanded the Union

soldiers at the surrender at Appomattox Courthouse: "At such a time and

under such conditions I thought it eminently fitting to show some token

of our feeling, and I therefore instructed my subordinate officers to

come to the position of [Carry Arms] 'salute' in the manual of arms as

each body of the Confederates passed before us... I may best describe it

as a marching salute in review. When General Gordon came opposite me I

had the bugle blown and the entire line came to 'attention,' preparatory

to executing this movement of the manual successively and by regiments

as Gordon's columns should pass before our front, each in turn. The

General was riding in advance of his troops, his chin drooped to his

breast, downhearted and dejected in appearance almost beyond

description. At the sound of that machine-like snap of arms, however,

General Gordon started, caught in a moment its significance, and

instantly assumed the finest attitude of a soldier. He wheeled his horse

facing me, touching him gently with the spur, so that the animal

slightly reared, and as he wheeled, horse and rider made one motion, the

horse's head swung down with a graceful bow, and General Gordon dropped

his sword point to his toe in salutation. . . .General Gordon sent back

orders to the rear that his own troops take the same position of the

manual in the march past as did our line. That was done, and a truly

imposing sight was the mutual salutation and farewell."

Gordon’s 1903 Reminiscences of the Civil War, confirmed

Chamberlain’s tale:" ...as my men marched in front of them, the veterans

in blue gave a soldierly salute to those vanquished heroes, a token of

respect from Americans to Americans, a final and fitting tribute from

Northern to Southern chivalry." Prof. Williams then shocked his students

by saying that there was no exchange of salutes. In fact

the Yankee soldiers had been taunting the defeated rebels and the

situation could easily have gotten out of hand. Any shifting of arms

that Gordon heard was the Yankees being called to Shoulder Arms

(attention), which meant they could not move and had to keep their

mouths shut. No Carry Arms (salute) was made by them, and Gordon made no

response. Chamberlain's motives for creating this myth are uncertain,

but Gordon gave credence to it as a way of uniting the postwar

generation. To date the first--and only-historian to set the record

straight is William Marvel in Lee's Last Retreat, published in

2002. The National Park Service perpetuates this benign fabrication: the

painting used to illustrate the surrender shows the Union soldiers at

Carry Arms! And the Civil War Trust reproduces Chamberlain’s 1901 Boston

Journal article quoted by Gordon in full!

Following Q&A, Prof. Hewitt received a well-deserved round of

applause.

Last changed: 03/09/14

Home

About News

Newsletters

Calendar

Memories

Links Join

|