Volume

27, No. 5 – May 2014

Volume 27, No. 5

Editor: Stephen L. Seftenberg

Website:

www.CivilWarRoundTablePalmBeach.org

President’s Message

The Roundtable extends its sympathy to Dorothy Segal on the death of

her husband, David P. Segal, a long-time member. We have two exciting

programs coming up in May and June. On May 14th, Dr. Gordon Dammann, one

of the leading authorities on Civil War medicine, and his son, Douglas

Dammann will speak. Dr. Dammann is the author of several books and the

founder of the National Museum of Civil War Medicine in Frederick,

Maryland. Douglas is the Curator of the Civil War Museum of Kenosha,

Wisconsin, whose unique mission is to focus on the impact before, during

and after the Civil War on the lives of people living in Illinois,

Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin, who together sent over

750,000 men to serve in the war. We will hear about both important

Museums. On June 11th, we will have a very special "interactive"

program: Member Craig Freis will bring to the meeting actual copies (not

replicas) of the New York Times from the 1850's and 1860's. Everyone

attending will have the rare privilege of reading the newspapers and

then sharing an article with the rest of us. The print is

small, so bring a magnifying glass!

April 9, 2014 Program: Veterinary and Human Medicine

in the Civil War

Dr. Robert Altman practiced as a veterinary doctor for many years. He

broke his talk into two sections:

PART I - VETERINARY MEDICINE AND THE CIVIL WAR

At the beginning of the 19th Century the few animal

practitioners in America were uneducated or at best self-educated. Many

were farriers and farmers with animal husbandry knowledge but no medical

knowledge. At the beginning of the Civil War there were only 50 graduate

veterinarians in the entire country, all graduates of European schools.

The first veterinary school, in Lyons, France, was established in 1762.

In contrast, the first veterinary college in the U.S. was opened n 1862

in Philadelphia. The college folded because of insufficient enrollment,

before any student could graduate. The New York College of veterinary

surgeons was founded in 1857 and graduated only two students in 1867.

Sixty one years later, in 1918, when we entered World War I, only 867

graduated. The New York State Veterinary College at Cornell was

established in 1876. Its first graduate was Daniel Elmer Salmon, who

went on to discover Salmonella (which was named after him). Dr. Altman’s

father was a veterinary doctor in the Veterinary Corps, serving in

France as a 1st Lieutenant in World War I.

The start of the Civil War witnessed the formation of

dozens of cavalry regiments requiring the service of thousands of

horses. A War Department General Order in May of 1861 provided for one

veterinary sergeant for every Union cavalry regiment but said nothing of

the qualifications necessary for the post. As late as 1863 there were

only six veterinarians in the Union army. The War Department increased

the rank given to veterinary sergeants to sergeants-major and then

changed the title to veterinary surgeons, who received a salary of $75 a

month.

In 1863 Giesboro Point (now headquarters of the

Defense Intelligence Agency), was the largest Union cavalry depot with

32 stables, 6,000 stalls and a veterinary hospital that could hold 2,650

injured animals. Due to overcrowding, disease was rampant and infectious

diseases such as glanders (Pseudomonas mallei nka Burkholderia

mallei), which caused fever, a thick nasal discharge, swelling of

glands in the neck region and often death. The long incubation period of

this disease delayed its diagnosis so it spread widely. At Giesboro over

17,000 horses died in three years.

A German immigrant, Gustavus Asche-Berg was trained as a veterinarian

and practiced in the Old World for 13 years and then

practiced human medicine in the new world before joining the Union

cause in the late summer of 1861. He first joined a Pennsylvania unit as

a human surgeon, but soon switched to the 4th New Cavalry as a

veterinarian. By March of 1862 a New York cavalry unit had lost 160 of

the 780 horses originally assigned to it. With a smaller horse supply

the Confederate States established giant horse infirmaries that

emphasized rehabilitation of disabled animals rather than just buying

new ones.

It is truly ironic that in the Civil War animals were treated by

human physicians and soldiers were treated by veterinarians.

PART II - HUMAN MEDICINE DURING THE CIVIL WAR

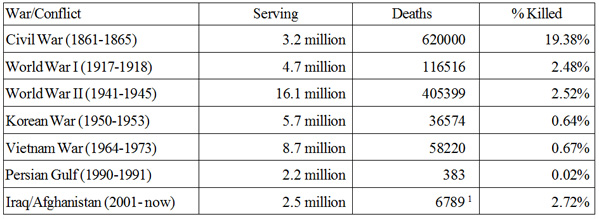

The Civil War is considered the deadliest war of all the wars in

which the United States has participated (see table). Approximately

620,000 men (360,000 Northerners and 260,000 Southerners died in the

four year conflict. Of these approximately 110,000 Union and 94,000

Confederate men died of wounds received in battle. The rest died of

disease.

1 Through the end of 2013.

When the Civil War started in 1861, there were 85

medical schools distributed throughout 25 states, including the District

of Columbia. All had small classes. Most of the surgeons in the war were

trained during the 1840s and 1850s. This period was considered the end

of the medical Middle Ages. Little was known about what caused disease,

how to stop it from spreading, or how to cure it. Surgical techniques

ranged from barbaric to barely competent. A Civil War soldier’s chance

of NOT surviving the war was about one in five. The fallen

men were cared for by an under qualified, understaffed, and

undersupplied medical corps. However, working against incredible odds,

the Medical Corps increased in size, improved its techniques and gained

a greater understanding of medicine and disease every year the war was

fought.

Prior

to the Civil War a physician received minimal training. Nearly all the

older doctors served as apprentices in lieu of a formal education. In

Europe four year medical schools were common, lab training was

widespread and a greater understanding of disease and infection existed.

Just before the Civil War the average medical student in the US trained

for only two years, had no clinical experience and no lab instruction.

Harvard Medical School did not own a single stethoscope or microscope

until after the war. In 1861, the Federal Army had a total of 98 Medical

officers and the Confederacy just 24. By 1865 the Union had 13,000

doctors and the Confederacy about 4,000. In addition, more than 4,000

women served as nurses in Union hospitals. By the end of the war army

doctors had treated more than 10 million wounded and sick men in just 48

months! When the war started, the US Army medical staff consisted of

only the Surgeon General, 30 surgeons and 83 assistant surgeons. Of

these, 24 resigned to go to the South and three were dropped for

disloyalty. At the end of the war in 1865, more than 11,000 doctors

served in varying capacities in the Union Army. Dr. Samuel Preston Moore

was given the rank of Colonel. To improve the quality of medical

practice, Moore insisted that every medical officer must pass an

examination set by one of his examining boards. He disliked filthy camps

and hospitals and believed in pavilion hospitals which were long wooden

buildings, well ventilated, with space for 80 to 100 beds. An important

reform was the establishment of the United States Sanitary Commission to

clean up the hospitals, speed up sanitary supplies to field hospitals,

general hospitals and hospital ships. Prior

to the Civil War a physician received minimal training. Nearly all the

older doctors served as apprentices in lieu of a formal education. In

Europe four year medical schools were common, lab training was

widespread and a greater understanding of disease and infection existed.

Just before the Civil War the average medical student in the US trained

for only two years, had no clinical experience and no lab instruction.

Harvard Medical School did not own a single stethoscope or microscope

until after the war. In 1861, the Federal Army had a total of 98 Medical

officers and the Confederacy just 24. By 1865 the Union had 13,000

doctors and the Confederacy about 4,000. In addition, more than 4,000

women served as nurses in Union hospitals. By the end of the war army

doctors had treated more than 10 million wounded and sick men in just 48

months! When the war started, the US Army medical staff consisted of

only the Surgeon General, 30 surgeons and 83 assistant surgeons. Of

these, 24 resigned to go to the South and three were dropped for

disloyalty. At the end of the war in 1865, more than 11,000 doctors

served in varying capacities in the Union Army. Dr. Samuel Preston Moore

was given the rank of Colonel. To improve the quality of medical

practice, Moore insisted that every medical officer must pass an

examination set by one of his examining boards. He disliked filthy camps

and hospitals and believed in pavilion hospitals which were long wooden

buildings, well ventilated, with space for 80 to 100 beds. An important

reform was the establishment of the United States Sanitary Commission to

clean up the hospitals, speed up sanitary supplies to field hospitals,

general hospitals and hospital ships.

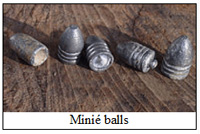

By

far the most common procedure performed in the civil war was amputation.

Almost any wound, no matter how minor, became infected. Without knowing

the cause of infection and having no medications to combat it, any wound

became infected -- mostly a Staph aureus or Strep pyogenes

bacteria. Although infection was an important reason to amputate, the

introduction of the Minié ball was

the greatest cause. The Minié ball

was invented by Claude-Étienne Minié,

an officer in the French army in the 1840s. It differed from the

standard round musket ball because of its conical shape and its hollow

base at the back of the bullet. When the trigger was pulled and the

gunpowder was ignited, the gasses formed would cause the hollow base of

the lead .58 caliber bullet to expand. The bullet would then snugly fit

into the rifled grooves of the gun barrel causing the bullet head to

spin when exiting the gun barrel giving it much greater accuracy and

increased range. This bullet caused devastating damage to both bone and

soft tissue. On entering a limb the bullet would pulverize bone and

muscle; ligaments and tendons were torn away. The wound was often 4 to 8

times larger than the base of the bullet and gangrene would inevitably

follow. Extremity wounds shattered the bone and carried dirt and

bacteria into the wound which invariably became infected. A little over

17% of extremity wounds led to amputations in both armies. Abdominal or

head wounds were almost always fatal. By

far the most common procedure performed in the civil war was amputation.

Almost any wound, no matter how minor, became infected. Without knowing

the cause of infection and having no medications to combat it, any wound

became infected -- mostly a Staph aureus or Strep pyogenes

bacteria. Although infection was an important reason to amputate, the

introduction of the Minié ball was

the greatest cause. The Minié ball

was invented by Claude-Étienne Minié,

an officer in the French army in the 1840s. It differed from the

standard round musket ball because of its conical shape and its hollow

base at the back of the bullet. When the trigger was pulled and the

gunpowder was ignited, the gasses formed would cause the hollow base of

the lead .58 caliber bullet to expand. The bullet would then snugly fit

into the rifled grooves of the gun barrel causing the bullet head to

spin when exiting the gun barrel giving it much greater accuracy and

increased range. This bullet caused devastating damage to both bone and

soft tissue. On entering a limb the bullet would pulverize bone and

muscle; ligaments and tendons were torn away. The wound was often 4 to 8

times larger than the base of the bullet and gangrene would inevitably

follow. Extremity wounds shattered the bone and carried dirt and

bacteria into the wound which invariably became infected. A little over

17% of extremity wounds led to amputations in both armies. Abdominal or

head wounds were almost always fatal.

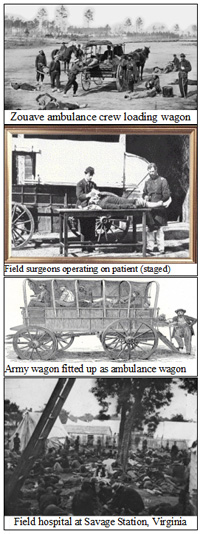

A

common surgeon’s tent in the field had tables or wood planks or old

doors placed on barrels where a surgeon and an assistant surgeon, often

stripped to the waist and spattered with blood, used a saw and a knife

to remove limbs very quickly, throwing the mangled limbs on a pile to be

removed later. Most amputees were administered chloroform or ether and

experienced little pain during the surgery. However, after surgery the

patient suffered a great deal of pain with no medication to offer

relief. Morphine was available but was used in limited doses. A

common surgeon’s tent in the field had tables or wood planks or old

doors placed on barrels where a surgeon and an assistant surgeon, often

stripped to the waist and spattered with blood, used a saw and a knife

to remove limbs very quickly, throwing the mangled limbs on a pile to be

removed later. Most amputees were administered chloroform or ether and

experienced little pain during the surgery. However, after surgery the

patient suffered a great deal of pain with no medication to offer

relief. Morphine was available but was used in limited doses.

Most surgeons were aware of the relationship between

cleanliness and low infection rates, but did not know how to sterilize

their instruments. Because of frequent water shortages, surgeons often

went without washing their hands or instruments thereby spreading

bacteria from one patient to another. Most infections were caused by

staph aureus and strep pyogenes. These organisms generate pus, destroy

tissue, and release toxins into the blood stream. Gangrene commonly

followed. Despite these fearful odds, 75% of the amputees survived. The

typical treatment protocol for wounds not treated by amputation was to

probe the wound for a bullet or shell or bone fragments. This was

generally done by the the surgeons unwashed hands. Bleeding blood

vessels were ligated and the wound was packed with lint. If the wound

could be closed it was sutured closed, and if not sutured the edges of

the wound were painted with iodine or other disinfectants such as

carbolic acid, bichloride of mercury or sodium hypochlorite.

Every effort was made to treat the wounded within 48

hours. Men were evacuated from the field, often several days after they

were injured because the battle was still on. They were usually carried

by litter bearers. Most primary care was administered at field hospitals

located behind the front lines. Those who survived were then transported

by unreliable and overcrowded ambulances–two wheeled carts and four

wheeled wagons and then put in two-wheeled carts and sometimes in

four-wheeled wagons, riding over rough ground without springs, making

the trip agonizing for a badly wounded patient to Army hospitals located

in nearby cities and towns.

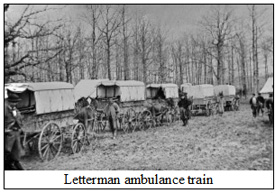

In

time for the Battle of Antietam (September 17, 1862), the Army of the

Potomac’s medical director, Dr. Jonathan Letterman, developed the

Letterman Ambulance Plan. In this system, the ambulances of a division

moved together, each ambulance under a mounted line Sergeant with two

stretcher-bearers and one driver, to collect the wounded from the field,

bring them to a field dressing station and then to the field hospital.

There were many ambulance designs though the Letterman Ambulance proved

to be the best. Most of the newer wagons had springs offering a much

smoother ride. Ambulance wagons carried both sitting and recumbent

patients. Where possible, railroads were used to evacuate wounded to

hospitals in major cities. Sadly, ward attendants and orderlies were

frequently recuperating patients, often barley able to care for

themselves. In

time for the Battle of Antietam (September 17, 1862), the Army of the

Potomac’s medical director, Dr. Jonathan Letterman, developed the

Letterman Ambulance Plan. In this system, the ambulances of a division

moved together, each ambulance under a mounted line Sergeant with two

stretcher-bearers and one driver, to collect the wounded from the field,

bring them to a field dressing station and then to the field hospital.

There were many ambulance designs though the Letterman Ambulance proved

to be the best. Most of the newer wagons had springs offering a much

smoother ride. Ambulance wagons carried both sitting and recumbent

patients. Where possible, railroads were used to evacuate wounded to

hospitals in major cities. Sadly, ward attendants and orderlies were

frequently recuperating patients, often barley able to care for

themselves.

Disease caused 60% of all deaths – half from

intestinal disorders (typhoid fever, diarrhea and dysentery), the

remainder from pneumonia and tuberculosis. Measles, chicken pox, mumps

and whooping cough were also prevalent. In the Southern areas, malaria

and yellow fever regularly swept through army camps and naval fleets. It

is estimated that 995 out of every 1,000 men contracted diarrhea. One

quarter of noncombat deaths in the Confederate Army was from typhoid

fever. A common cold often developed into pneumonia, the third leading

killer after typhoid fever and dysentery. The brilliant results from

cleaning up the Crimean War hospitals by Florence Nightingale inspired

the North to add nurses to the Army under the supervision of Dorothea

Dix. Sadly, she was disorganized, unyielding in controversy and deeply

imbued with Victorian principles, and the doctors hated her. By

contrast, Clara Barton, the founder of the American Red Cross, did an

admirable job with the wounded and sick soldiers, winning over the

doctors.

Contrary to common belief, anesthesia was used in

most amputations and other surgeries. Chloroform, ether, or a

combination of the two were used. Chloroform was preferred by far

because of ether’s explosive properties, particularly in a field

hospital where bullets or exploding cannon balls could trigger an

explosion. The most common method of administering chloroform and ether

was through a cloth or paper folded into a cone with a sponge or cloth

soaked in the anesthetic fluid in the apex. The cone was held at some

distance over the nose and mouth of the patient to allow the first few

inhalations to become diluted with air and then allow the cone to be

lowered to the nose until anesthesia was effected. The breathing of the

patient had to be monitored very carefully because there was very little

margin of error between anesthesia and death, particularly with

chloroform. Anesthetic deaths were surprisingly low considering the

crude means of administration. With chloroform anesthetic deaths

occurred in 5.4 per thousand cases, and with ether 3.0 deaths per

thousand, but chloroform was preferred because of ether’s tendency to

explode.

In the Southern army, where chloroform was scarce,

Surgeon J. J. Chisolm devised a cylinder 2½ inches long and one inch wide with a perforated plate on one of its

surfaces and a cover with nose pieces. Chloroform could then be poured

thru the perforated plate onto a sponge or cotton and inhaled by the

patient thru the nose pieces. Both chloroform and ether evaporated in

the air quickly. This method was a vast improvement over the open drip

technique where much of the anesthetic liquids would evaporate and be

lost, particularly when the surgery was done in the field.

inches long and one inch wide with a perforated plate on one of its

surfaces and a cover with nose pieces. Chloroform could then be poured

thru the perforated plate onto a sponge or cotton and inhaled by the

patient thru the nose pieces. Both chloroform and ether evaporated in

the air quickly. This method was a vast improvement over the open drip

technique where much of the anesthetic liquids would evaporate and be

lost, particularly when the surgery was done in the field.

Dr. Altman closed his talk by saying, "It amazes me

how in those chaotic times record keeping was as efficient and complete

as it was."

After a question and answer session, Dr. Altman received a

well-deserved round of applause for his efforts.

Last changed: 05/10/14

Home

About News

Newsletters

Calendar

Memories

Links Join

|