Volume

27, No. 6 – June 2014

Volume 27, No. 6

Editor: Stephen L. Seftenberg

Website:

www.CivilWarRoundTablePalmBeach.org

President’s Message

What an exciting six months we have had at the Round Table! Thank you

to everyone who has supported our efforts through your dues and

donations and participation in our programs. Special recognition goes to

Robert Franke and Marshall Krolick for their outstanding efforts in

making our guests speaker’s visits possible. In December 2013,

world-famous author Robert Macomber’s entertaining account of the role

of the Bahamas in the Civil War highlighted our Holiday Party. In

January, General Dan Sickles (embodied by member William McEachern)

returned from "the other side" for a unique interview by intrepid

reporter, Lavinia Lovejoy Lawrence (embodied by President LaRovere). In

February, Larry Hewitt discussed "Civil War Myths and Mythmakers." In

March, 105 attendees listened as Dr. James "Bud" Robertson discussed his

new book, "The Untold Civil War." In April, member, Dr. Robert Altman

discussed veterinary and human medicine. And in May, the dynamic duo of

Dr. Gordon Dammann, founder of the National Museum of Civil War

Medicine, Frederick, Maryland, and his son, Douglas Dammann, Curator of

the Civil War Museum of Kenosha, Wisconsin, shared the stage.

We had outstanding attendance at each of these programs. However, the

record for the number of members attending a program was set by

Roundtable member Dr. Marsha Sonnenblick, ably assisted by her husband,

Dr. Bernie Sonnenblick. The subject was "Sex and the Civil War," given

on Valentine’s Day 2013! Sex always draws a crowd!

June 11, 2014 Program

Craig Freis has been collecting autographs, historical documents, and

old newspapers for over forty years. Craig will bring actual editions of

newspapers such as The New York Times and the New

York Herald dated between 1850 and 1870. Round Table members

will have the opportunity to read about social, economic, and political

topics as well as news and casualties from the battlefront. Feel tired

and run down? Read about the latest elixir advertised in the newspaper.

The print is very, very small so please

bring a magnifying glass or very strong glasses. Craig is a retired

investigator in the mental health system in New York.

May 14, 2014 Program

Gordon

E. Dammann, DDS, and his son, Douglas Dammann, combined to give us two

fascinating talks. Doug was first on the bill. Kenosha, Wisconsin, is a

town of 100,000 equidistant from Chicago and Milwaukee. The Museum is

one of three museums opened by the City of Kenosha in 2008. Member

Marshall Krolick served as a curator and loaned the Museum many items

from his personal collection. We are the lucky benefactors of the fact

that Gordon and Doug drove to Florida to return these items and agreed

to speak to us. The Civil War Museum draws 75,000 visitors a year (out

of 235,000 a year total for the three museums). Why choose Kenosha?

There are few battlefields to visit, but 750,000 young men from

Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin, Illinois (250,000 alone), Indiana and

Michigan went off to "See the Elephant." In addition, the Middle Western

states supplied iron ore, grain, horses, mules, foodstuffs, etc. "Seeing

the Elephant" was the term Civil War soldiers used to say they saw

battle and is the title of the Museum’s 11-minute 360-degree Cyclorama

that puts you right in the middle of the battle. Gordon

E. Dammann, DDS, and his son, Douglas Dammann, combined to give us two

fascinating talks. Doug was first on the bill. Kenosha, Wisconsin, is a

town of 100,000 equidistant from Chicago and Milwaukee. The Museum is

one of three museums opened by the City of Kenosha in 2008. Member

Marshall Krolick served as a curator and loaned the Museum many items

from his personal collection. We are the lucky benefactors of the fact

that Gordon and Doug drove to Florida to return these items and agreed

to speak to us. The Civil War Museum draws 75,000 visitors a year (out

of 235,000 a year total for the three museums). Why choose Kenosha?

There are few battlefields to visit, but 750,000 young men from

Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin, Illinois (250,000 alone), Indiana and

Michigan went off to "See the Elephant." In addition, the Middle Western

states supplied iron ore, grain, horses, mules, foodstuffs, etc. "Seeing

the Elephant" was the term Civil War soldiers used to say they saw

battle and is the title of the Museum’s 11-minute 360-degree Cyclorama

that puts you right in the middle of the battle.

Doug

then introduced us to Carolyn Quarlls (1850-1910), a light-skinned slave

who could pass for white. On July 4th, 1842, Caroline Quarlls, with $100

she had secretly accumulated, left family, friends, and the only life

she'd known behind in St. Louis, Missouri. As the child of a slave

mother and a slave-owner father, her young life was one of drudgery and

obedience until that fateful Independence Day when she illegally took a

steamboat across the Mississippi River from St. Louis to Alton,

Illinois, in the hope of reaching freedom. With the help of

abolitionists, especially her "conductor," Lyman Goodnow, of

Prairieville (now Waukesha), Wisconsin, the 16-year-old traveled through

Illinois, Wisconsin, Indiana, and Michigan on the Underground Railroad,

enduring long, bumpy rides in the bottom of wagons and taking cover in

everything from barrels to potato chutes. Each step of the way, Quarlls

was pursued by lawyers paid to retrieve her and bounty hunters greedy

for the reward money (If she escaped, the steam boat company would have

to reimburse her owner for her "value") and was nearly caught in

Milwaukee because of the treachery of a black barber who pretended to

hide her. Finally, she crossed from Detroit into Sandwich, Canada, where

she created a new life as a free woman, an exciting but also frightening

experience. She married another escaped slave and bore six children.

Carolyn wrote two letters 35 years later and her husband wrote one

letter. These letters are primary sources for the Underground Railroad

story related by Goodnow in his "History of Waukesha County, Wisconsin."

Unfortunately, no good picture of her exists. Doug

then introduced us to Carolyn Quarlls (1850-1910), a light-skinned slave

who could pass for white. On July 4th, 1842, Caroline Quarlls, with $100

she had secretly accumulated, left family, friends, and the only life

she'd known behind in St. Louis, Missouri. As the child of a slave

mother and a slave-owner father, her young life was one of drudgery and

obedience until that fateful Independence Day when she illegally took a

steamboat across the Mississippi River from St. Louis to Alton,

Illinois, in the hope of reaching freedom. With the help of

abolitionists, especially her "conductor," Lyman Goodnow, of

Prairieville (now Waukesha), Wisconsin, the 16-year-old traveled through

Illinois, Wisconsin, Indiana, and Michigan on the Underground Railroad,

enduring long, bumpy rides in the bottom of wagons and taking cover in

everything from barrels to potato chutes. Each step of the way, Quarlls

was pursued by lawyers paid to retrieve her and bounty hunters greedy

for the reward money (If she escaped, the steam boat company would have

to reimburse her owner for her "value") and was nearly caught in

Milwaukee because of the treachery of a black barber who pretended to

hide her. Finally, she crossed from Detroit into Sandwich, Canada, where

she created a new life as a free woman, an exciting but also frightening

experience. She married another escaped slave and bore six children.

Carolyn wrote two letters 35 years later and her husband wrote one

letter. These letters are primary sources for the Underground Railroad

story related by Goodnow in his "History of Waukesha County, Wisconsin."

Unfortunately, no good picture of her exists.

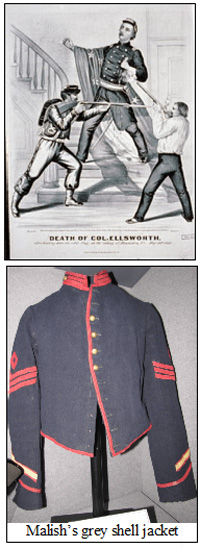

Col.

Elmer Ellsworth (1837-1861) was the first Union soldier killed in the

Civil War. Born in New York, he moved to Rockford, Illinois, and married

there. Ellsworth became drillmaster of the "Rockford Greys," the local

militia company, in 1857. He outfitted his men in gaudy Zouave-style

uniforms and modeled their drill and training on the French Zouaves.

Ellsworth's unit eventually became a nationally famous drill team. In

1860, Ellsworth went to Springfield, Illinois, to study law in Abraham

Lincoln's office and helped Lincoln with his 1860 campaign for

president. Ellsworth was only 5' 6" tall, but Lincoln called Ellsworth

"the greatest little man I ever met." He accompanied Lincoln to

Washington, D.C. in 1861. When Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers,

Ellsworth raised the 11th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment (the

"Fire Zouaves") from New York City's volunteer firefighting companies

and returned to Washington as their colonel. On May 24, 1861, Ellsworth

was shot dead by the owner of the Marshall House in Alexandria,

Virginia, as he came down the stairs with the Confederate flag. When

Lincoln heard of Ellsworth’s death, he exclaimed, "My boy, my boy. Was

it necessary that this sacrifice be made?" Col.

Elmer Ellsworth (1837-1861) was the first Union soldier killed in the

Civil War. Born in New York, he moved to Rockford, Illinois, and married

there. Ellsworth became drillmaster of the "Rockford Greys," the local

militia company, in 1857. He outfitted his men in gaudy Zouave-style

uniforms and modeled their drill and training on the French Zouaves.

Ellsworth's unit eventually became a nationally famous drill team. In

1860, Ellsworth went to Springfield, Illinois, to study law in Abraham

Lincoln's office and helped Lincoln with his 1860 campaign for

president. Ellsworth was only 5' 6" tall, but Lincoln called Ellsworth

"the greatest little man I ever met." He accompanied Lincoln to

Washington, D.C. in 1861. When Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers,

Ellsworth raised the 11th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment (the

"Fire Zouaves") from New York City's volunteer firefighting companies

and returned to Washington as their colonel. On May 24, 1861, Ellsworth

was shot dead by the owner of the Marshall House in Alexandria,

Virginia, as he came down the stairs with the Confederate flag. When

Lincoln heard of Ellsworth’s death, he exclaimed, "My boy, my boy. Was

it necessary that this sacrifice be made?"

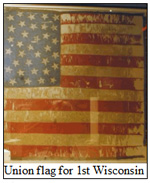

When

the 1st Wisconsin Volunteers signed up for 90 days, they had to wear

grey wool uniforms because there wasn’t enough blue wool. They trained

at Camp Randall, Wisconsin (now home of the Wisconsin Badgers). The

ladies of Kenosha sewed a 34-star Union flag for this unit. On July 2,

1861, this unit fought at the Battle of Falling Waters, Virginia (now

Martinsburg, West Virginia). Fred Malish, a German émigré, had enlisted

for 90 days, but like over two-thirds of his regiment, reenlisted for

three years after his 90 days were up. The flag (left) and Malish’s grey

shell jacket (right) are on display at the Museum. When

the 1st Wisconsin Volunteers signed up for 90 days, they had to wear

grey wool uniforms because there wasn’t enough blue wool. They trained

at Camp Randall, Wisconsin (now home of the Wisconsin Badgers). The

ladies of Kenosha sewed a 34-star Union flag for this unit. On July 2,

1861, this unit fought at the Battle of Falling Waters, Virginia (now

Martinsburg, West Virginia). Fred Malish, a German émigré, had enlisted

for 90 days, but like over two-thirds of his regiment, reenlisted for

three years after his 90 days were up. The flag (left) and Malish’s grey

shell jacket (right) are on display at the Museum.

Samuel Bennett, of Beaver Dam, Wisconsin, wrote eight letters to his

wife, which are on display at the Museum. While one-third of the

Wisconsin boys came from German states, Bennett emigrated from England.

When the war started, Bennett was sent to Southern Mississippi, where he

died of a disease. Benjamin Franklin White was born in Green Bay,

Wisconsin. He and his parents went West on the Oregon Trail. He received

a degree from Read Medical College in 1857. When the war started, he

became a Lieutenant Colonel in the 1st Wisconsin Infantry but went home

after his 90-day enlistment expired. He was then hired as a "contract"

surgeon to treat the 1200 Confederate prisoners held at Camp Randall.

Unfortunately, he died of heat stroke in May 1862.

Peter Ford fought with the 1st Wisconsin (the "Iron Brigade"), an all

western regiment with three Wisconsin, one Indiana and one Michigan

brigades. He was captured and paroled after Antietam but was killed on

July 3, 1863 and is buried in the Gettysburg National Cemetery.

Milwaukee women raised $100,000 to start an asylum for Union soldiers

and sailors. They turned the money over to the Federal Government to

establish the Northwestern branch of the National Soldiers’ and Sailors

Home (now the Clement J. Zablocki VA Medical Center) on 125 rolling

acres in western Milwaukee.

Twelve Union veterans started the Grand Army of the Republic in

Decatur, Illinois. By 1890, the GAR grew to a 400,000-strong Republican

voting bloc and exerted substantial, long-lasting influence on politics,

especially veteran’s pensions. GAR ribbons are displayed at the Kenosha

Museum.

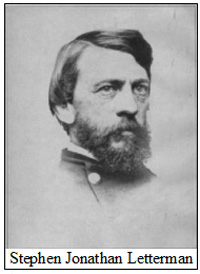

Doug

then turned the podium over to his father. Gordon began by introducing

us to Stephen Jonathan Letterman (1824-72) and William Alexander

Hammond, two true heroes of the Civil War. Known as the "Father of

Modern Battlefield Medicine," Letterman’s work saved thousands of

soldiers from dying horrible deaths on the battlefield. Letterman was

born in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania. His father was a surgeon, and

Letterman followed in his footsteps, graduating from Jefferson Medical

College, in Philadelphia, in 1849. His medical education consisted of

two 8-month terms at which the same classes were repeated. If the

student passed an exam, he received a medical degree. He then joined the

Army and passed a 3-day test (only 9 out of 50 passed!), upon which he

was commissioned as an assistant surgeon in the Army Medical Department.

From then until 1861, Letterman served on various military campaigns

against Native American tribes in Florida, Minnesota, Kansas, New Mexico

and California. With the beginning of the Civil War in 1861, Letterman

was assigned to the Army of the Potomac and was eventually named Medical

Director of the entire army in June 1862, with the rank of Major. After

it took over a week to remove 3,626 casualties from the battlefield at

Second Manassas/Bull Run, Letterman was given free range by General

George McClellan to do whatever was needed to revamp the poor medical

services that the men received in the field. Doug

then turned the podium over to his father. Gordon began by introducing

us to Stephen Jonathan Letterman (1824-72) and William Alexander

Hammond, two true heroes of the Civil War. Known as the "Father of

Modern Battlefield Medicine," Letterman’s work saved thousands of

soldiers from dying horrible deaths on the battlefield. Letterman was

born in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania. His father was a surgeon, and

Letterman followed in his footsteps, graduating from Jefferson Medical

College, in Philadelphia, in 1849. His medical education consisted of

two 8-month terms at which the same classes were repeated. If the

student passed an exam, he received a medical degree. He then joined the

Army and passed a 3-day test (only 9 out of 50 passed!), upon which he

was commissioned as an assistant surgeon in the Army Medical Department.

From then until 1861, Letterman served on various military campaigns

against Native American tribes in Florida, Minnesota, Kansas, New Mexico

and California. With the beginning of the Civil War in 1861, Letterman

was assigned to the Army of the Potomac and was eventually named Medical

Director of the entire army in June 1862, with the rank of Major. After

it took over a week to remove 3,626 casualties from the battlefield at

Second Manassas/Bull Run, Letterman was given free range by General

George McClellan to do whatever was needed to revamp the poor medical

services that the men received in the field.

Before Letterman’s innovations, wounded men were often left to fend

for themselves. Unless carried off the field by a comrade or one of the

regimental musicians doubling as a stretcher bearer, a wounded soldier

could lie for days suffering from exposure, thirst and being burned

alive. Letterman started the very first Ambulance Corps, training men to

act as stretcher bearers and operate wagons to pick up the wounded and

bring them to field dressing stations. He also instituted the concept of

"triage" for treatment of the casualties (dividing casualties into three

groups: can be saved, might be saved and cannot be saved).

Letterman developed an evacuation system that consisted of three

stations:

1) A Field Dressing Station - located on or next to the

battlefield where medical personnel would apply the initial

dressings and tourniquets to wounds.

2) A Field Hospital – located close to the battlefield, usually

in homes or barns, where emergency surgery could be performed and

additional treatment given.

3) A Large Hospital – Located away from the battlefield and

providing facilities for the long term treatment of patients.

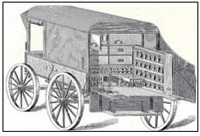

In addition to these improvements, Letterman arranged for an

efficient distribution system for medical supplies; developed a standardized medical box containing 60

different medicines, including condensed milk and coffee grounds,

costing $125 and built by Edward R. Squibb; designed a pharmacy wagon

(right), placed first aid stations within 60 yards of the battle (!);

insisted they be placed in low areas which were safer from shells and

bullets; and as part of triage, bandaged soldiers who could return and

sent them back to the front. On August 27, 1862, Gen. McClellan issued

General Order No. 147, spelling out in great detail how the ambulance

corps and ambulance trains were to be organized and operated.

medical supplies; developed a standardized medical box containing 60

different medicines, including condensed milk and coffee grounds,

costing $125 and built by Edward R. Squibb; designed a pharmacy wagon

(right), placed first aid stations within 60 yards of the battle (!);

insisted they be placed in low areas which were safer from shells and

bullets; and as part of triage, bandaged soldiers who could return and

sent them back to the front. On August 27, 1862, Gen. McClellan issued

General Order No. 147, spelling out in great detail how the ambulance

corps and ambulance trains were to be organized and operated.

The success of the Ambulance Corps was proven at the Battle of

Antietam, September 17, 1862. While there were over 23,000 casualties,

medical personnel were able to remove all of the wounded from the field

in just 24 hours. Within 48 hours, 90% were being treated in one of 34

Union hospitals where there would be fresh water, fresh straw and fresh

food. He set up his own convoy system, manned by men trained to care for

the wounded, unlike the Quarter Master Corpsmen! The trains left for

Middleton, Maryland, where wounded were taken into a church, had their

wounds redressed, and were required to rest for six hours before being

put back on board trains headed for Frederick, Maryland, the "City of

Church Spires." All six churches there were utilized – wooden planks

were laid across the pews. The Catholic Sisters of Charity served as

nurses. In addition, soldiers’ wives and widows were paid 20 cents a day

and trained to be nurses.

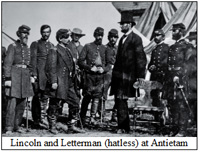

The

morale of the wounded improved, which improved their chances of

surviving. Letterman himself did no cutting. Instead he was like a

symphony conductor. Letterman was extraordinarily energetic and

impatient. In October 1862, President Lincoln visited the Army. There is

a picture (right) of Lincoln and the generals, along with Letterman

(second from left), who looks impatient with the whole process, itching

to get back to work! Lincoln asked Letterman for a tour of the

hospitals, saying he wanted to see the wounded of both sides. The

President knelt beside the cot of a dying 18-year old rebel and had a

private 3-minute conversation. Letterman saw tears in Lincoln’s eyes and

heard him say, "When will this horrible war end?" The

morale of the wounded improved, which improved their chances of

surviving. Letterman himself did no cutting. Instead he was like a

symphony conductor. Letterman was extraordinarily energetic and

impatient. In October 1862, President Lincoln visited the Army. There is

a picture (right) of Lincoln and the generals, along with Letterman

(second from left), who looks impatient with the whole process, itching

to get back to work! Lincoln asked Letterman for a tour of the

hospitals, saying he wanted to see the wounded of both sides. The

President knelt beside the cot of a dying 18-year old rebel and had a

private 3-minute conversation. Letterman saw tears in Lincoln’s eyes and

heard him say, "When will this horrible war end?"

The Battle of Fredericksburg (December 11-15, 1862) (12,000

casualties) tested Letterman’s system to the "max." Within two days

after this disaster ended, Letterman’s team had installed pontoon

bridges across the Rappahannock River; ambulance convoys crossed and

re-crossed the river; and all casualties that could be moved had been

sent to hospitals in Washington, D. C. Letterman established a General

Hospital ("Camp Letterman") about a mile from the battle site and

temporary field hospitals wherever there was a source of water and

shelter. The buildings used included churches, farm buildings and

private homes. Sometimes the only shelter available was a piece of

canvas strung between two trees or poles.

As the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1-3, 1863) approached its end,

there were approximately 22,000 wounded from both the Union and

Confederate armies to deal with. To Letterman, once a man was wounded he

was no longer an "enemy." Medical supplies were running low and the

hardships of the wounded were equally matched with the exhaustion of the

doctors (both Union and Confederate). During the first days of the

battle, Gen. Meade had barred Letterman’s supply wagons from the

battlefield. Meade wanted ammunition and more ammunition, but after 48

hours, Meade relented. Letterman felt devastated by what he called "a

vast sea of misery." Camp Letterman was primitive by modern standards,

but was impressive to the soldiers. Each tent held forty folding cots

with mattresses and sheets--luxuries for soldiers who were used to lying

on hard ground since being wounded. In March of 1864, the system was

officially adopted for the U.S. Army by an Act of Congress.

With his work with the Army Medical Corps completed, and in October

1863, he married Mary Digges Lee, from a wealthy family in Maryland,

with whom he was to have two daughters. After serving a brief period as

Inspector of Hospitals, Letterman resigned from the army in December

1864. He and his family moved to San Francisco where he served as

coroner from 1867 to 1872, and published his memoirs, Medical

Recollections of the Army of the Potomac. In 1872, after the death

of his wife, Letterman became severely depressed. Several illnesses

followed and on March 15, he passed away. He and his wife are buried

side-by-side in Arlington National Cemetery where his gravestone honors

the man "who brought order and efficiency in to the Medical Service and

who was the originator of modern methods of medical organization in

armies."

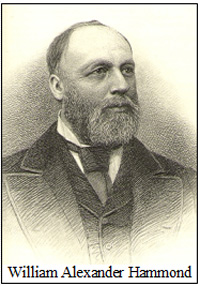

The

story of Civil War battlefield medicine would not be complete without

reference to William Alexander Hammond (1828-1900), then a 34-year old

Brigadier General and the 11th Surgeon General of the Army. Hammond

launched a number of reforms, including raising the requirements for

admission into the Army Medical Corps, weeding out incompetent

"sawbones," increasing the number of hospitals, improving record

keeping, transferring the responsibility for sanitary trains from

private companies to the government and paying close attention to

aeration. Gordon reminded us that to the amazement of old-line doctors,

casualties living outdoors in tents had a better survival record than

casualties packed into fetid barns. Hammond created Satterlee Hospital,

in Philadelphia (which had up to 4,500 beds in hundreds of tents).

Hammond proposed a permanent military medical corps, a permanent

hospital for the military, centralized issuance of medications and

personally oversaw the building of the wagons. He promoted Letterman and

supported his reforms. Efficiency increased, as Hammond promoted people

on the basis of competence, not rank or connections, and his initiatives

were positive and timely. He designed innovative hospitals, using a

wheel and spoke design: The operating rooms were in the center and each

spoke isolated contagious patients. Beds had to be placed a set distance

from each other. Walt Whitman chronicled his experiences in the

Washington, D. C., hospitals. The

story of Civil War battlefield medicine would not be complete without

reference to William Alexander Hammond (1828-1900), then a 34-year old

Brigadier General and the 11th Surgeon General of the Army. Hammond

launched a number of reforms, including raising the requirements for

admission into the Army Medical Corps, weeding out incompetent

"sawbones," increasing the number of hospitals, improving record

keeping, transferring the responsibility for sanitary trains from

private companies to the government and paying close attention to

aeration. Gordon reminded us that to the amazement of old-line doctors,

casualties living outdoors in tents had a better survival record than

casualties packed into fetid barns. Hammond created Satterlee Hospital,

in Philadelphia (which had up to 4,500 beds in hundreds of tents).

Hammond proposed a permanent military medical corps, a permanent

hospital for the military, centralized issuance of medications and

personally oversaw the building of the wagons. He promoted Letterman and

supported his reforms. Efficiency increased, as Hammond promoted people

on the basis of competence, not rank or connections, and his initiatives

were positive and timely. He designed innovative hospitals, using a

wheel and spoke design: The operating rooms were in the center and each

spoke isolated contagious patients. Beds had to be placed a set distance

from each other. Walt Whitman chronicled his experiences in the

Washington, D. C., hospitals.

Sadly, Hammond came a cropper in part due to his impatience with

incompetence. On 4 May 1863 Hammond banned the mercury compound calomel,

a purgative, from army supplies, as he believed it to be neither safe

nor effective (he was later proved correct). He thought it dangerous to

make an already debilitated patient vomit. A "Calomel Rebellion" ensued,

as many doctors saw the move as "infringing" on their liberty of

practice. Hammond's arrogant nature did not help him solve the problem,

and his relations with Secretary of War Stanton became strained. On

September 3, 1863 he was sent on a protracted "inspection tour" to the

South, effectively removing him from office. Joseph Barnes, a friend of

Stanton's and his personal physician, became acting Surgeon General.

Hammond demanded to be either reinstated or court-martialed. A

court-martial found him guilty of "irregularities" in the purchase of

medical furniture on the basis of "false data." Hammond was dismissed

from the Army on August 18, 1864. He went on to a varied and successful

career and is also buried in Arlington.

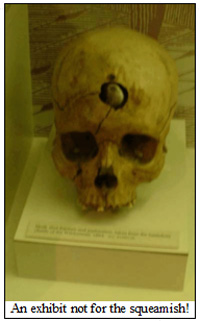

Gordon

said the Civil War was a turning point in the history of medicine.

Before, hospitals were referred to as "pest houses" and the sick and

injured were well-advised to insist on home care. Things changed slowly:

Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes once said, "All the drugs used by the armies

should be thrown into the ocean. Of course, all the fish would then

die!" In 1860, there was one Federal hospital, in Fort Leavenworth,

Kansas. In Washington, D. C., alone, 26 hospitals were set up! Hundreds

of hospitals sprouted up around the Confederacy. The five converging

railroads at Richmond, and the city’s proximity to the Eastern

battlefields, meant that Richmond, Virginia, became a booming hospital

center. No medical facility anywhere on the continent during the Civil

War equaled the fame of Chimborazo Hospital as one of the largest,

best-organized, and most sophisticated hospitals in the Confederacy. It

served as a convalescent hospital, treating wounded who had received

medical treatment elsewhere. During the war, it is estimated that 75,000

men were treated, of whom 5,000 to 7,000 died. From 1861 on, Dr. James

B. McCaw, a young resident of Richmond, ran the hospital (right), which

had its own dairy and vegetable garden and butchered its own beef. It

was built on top of a hill to escape some of Richmond’s summer heat. Gordon

said the Civil War was a turning point in the history of medicine.

Before, hospitals were referred to as "pest houses" and the sick and

injured were well-advised to insist on home care. Things changed slowly:

Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes once said, "All the drugs used by the armies

should be thrown into the ocean. Of course, all the fish would then

die!" In 1860, there was one Federal hospital, in Fort Leavenworth,

Kansas. In Washington, D. C., alone, 26 hospitals were set up! Hundreds

of hospitals sprouted up around the Confederacy. The five converging

railroads at Richmond, and the city’s proximity to the Eastern

battlefields, meant that Richmond, Virginia, became a booming hospital

center. No medical facility anywhere on the continent during the Civil

War equaled the fame of Chimborazo Hospital as one of the largest,

best-organized, and most sophisticated hospitals in the Confederacy. It

served as a convalescent hospital, treating wounded who had received

medical treatment elsewhere. During the war, it is estimated that 75,000

men were treated, of whom 5,000 to 7,000 died. From 1861 on, Dr. James

B. McCaw, a young resident of Richmond, ran the hospital (right), which

had its own dairy and vegetable garden and butchered its own beef. It

was built on top of a hill to escape some of Richmond’s summer heat.

Gordon is too humble to talk about his role in founding the National

Museum of Civil War Medicine, Frederick, Maryland, so your Editor took

the liberty of going to its website for the story:

"The creation of The National Museum of Civil War Medicine started as

the idea of Gordon E. Dammann, D.D.S., whose collection of medical

artifacts from the Civil War forms the core of the Museum’s holdings.

Dr. Dammann had begun collecting in 1971 and around 1990 felt that a

museum would be a good way to share his collection and the story of

Civil War medicine with the public. With the help of other doctors and

the support of the Governor of Maryland and the Mayor and Aldermen of

Frederick, what began as Gordon’s private collection of medical

artifacts from the Civil War has grown into an organization (that opened

its doors to the public on June 15, 1996) as vital and relevant as the

plan that Dr. Jonathan Letterman developed nearly 150 years ago while at

the Pry House on the Antietam battlefield. The legacy of the Letterman

Plan breathes life into the artifacts preserved and interpreted at the

Museum’s main site in Frederick, Maryland, and two satellite museums:

the Pry House Field Hospital Museum, Antietam, Maryland (next page), and

Clara Barton’s Missing Soldiers Office in Washington, D. C. The

Letterman Institute of Professional Development offers speakers and

seminars and the Museum also has a publishing center.

"Visitors

will find a unique center of Civil War history, guiding "Visitors

will find a unique center of Civil War history, guiding them through 150 years of medical history as well as Civil War camp

life, hospital life, African American life, the role of women and

children during the war, and many more aspects of American history

during the Civil War era. The Museum highlights the challenges faced by

Civil War doctors and surgeons and the resulting innovations that led to

the today’s modern military medical system. Our museum sites begin with

displays and artifacts highlighting general medicine in the 1800s

progressing into wartime medicine and civilian life. We look at the

faces of those who were treated and their caregivers. Reading their

stories and memories puts a human face on the medicine of the time. A

space in each museum is dedicated to Dr. Letterman, Medical Director of

the Army of the Potomac. His cohesive plan of triage, evacuation,

hospital and supply organization not only saved the lives of countless

Civil War soldiers, it continues to save lives on today’s battlefields

in Iraq, Afghanistan, and in civilian life wherever emergency medical

help is needed.

them through 150 years of medical history as well as Civil War camp

life, hospital life, African American life, the role of women and

children during the war, and many more aspects of American history

during the Civil War era. The Museum highlights the challenges faced by

Civil War doctors and surgeons and the resulting innovations that led to

the today’s modern military medical system. Our museum sites begin with

displays and artifacts highlighting general medicine in the 1800s

progressing into wartime medicine and civilian life. We look at the

faces of those who were treated and their caregivers. Reading their

stories and memories puts a human face on the medicine of the time. A

space in each museum is dedicated to Dr. Letterman, Medical Director of

the Army of the Potomac. His cohesive plan of triage, evacuation,

hospital and supply organization not only saved the lives of countless

Civil War soldiers, it continues to save lives on today’s battlefields

in Iraq, Afghanistan, and in civilian life wherever emergency medical

help is needed.

"The interactive experience that is the National Museum of Civil War

Medicine not only gives a snapshot of Civil War medicine, including

dentistry, veterinary medicine and medical evacuation, it allows

visitors to put faces and names to those who fought, were injured, the

surgeons and caregivers who tended them. The experience is a personal

one, engaging visitors in the stories of soldiers, surgeons, hospital

stewards, nurses and those who volunteered, as they gain an

understanding of the medical advances of the time. For some, a bit of

family history may be found as well."

Following an extended question-and-answer period, Dammann father and

son received a well-deserved round of applause.

[Editor’s addendum: The May 27, 2014, The New York Times

had a story on Andrew Carroll, an author and instructor at Chapman

University, Orange, California, who at his own expense, installs plaques

commemorating undeservedly overlooked people. One of his heroes was Dr.

Thomas Holmes, the "Father of American Embalming," who developed a more

efficient technique to preserve the remains of soldiers killed during

the Civil Wars, starting in 1861 when he embalmed the remains of Col.

Elmer Ellsworth, the first Union soldier killed in the war. His process

permitted the remains of thousands of soldiers to be sent home for

burial.]

[Free blurb for NMCWM: "Civil War Medicine…it’s not what you

think! Come learn the facts at the Twenty-second Annual Conference

on Civil War Medicine, Friday-Sunday, Oct. 3-5, 2014. The National

Museum of Civil War Medicine has assembled an impressive panel of

prominent historians, authors, and medical professionals speaking on a

wide variety of topics relating to Civil War medicine. Highlights of the

conference include eleven unique lectures on Friday, Saturday and

Sunday, and a special bus tour of the hospital and medical sites in

Kennesaw, GA. Back by popular demand is our Thursday evening

pre-conference program. Conference attire is casual. Period clothing is

welcome at the Saturday dinner. For further information, contact Tom

Frezza, PryHouse@civilwarmed.org, or call 301-695-1864, ext. 14."]

Last changed: 06/11/14

Home

About News

Newsletters

Calendar

Memories

Links Join

|