|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"We owe the formation of the Palm Beach County Round Table to President Robert Godwin. After many years as an avid historian, Bob obtained information on how to organize a local Civil War Round Table. From a subscription list provided by the Civil War Times Illustrated, the Club began to meet on a regular basis with Robert Godwin, Dr. Joel Gordon, Steve Carr and Rodney Dillon in attendance. We created an official constitution and by-laws that established a formal organization with the annual election of officers and a dues structure. Membership growth has been steady and prospects for the future seem favorable." |

Our Round Table could not have grown into the successful organization that it is today without the help of its members. I would like to thank everyone who has attended the meetings, given a presentation, brought refreshments, set up our website and edited Haversacks and Saddlebags. Your continued support will help make the Club even stronger. A very special thanks to the officers and committee chairs who have graciously served the Round Table through the years. Keep up the good work! Happy Anniversary, Round Table! Gerridine LaRovere

September 10, 2014 Program

Robert Krasner will clear up misconceptions about "The Confederate Medal of Honor:" Although the Confederate States of America created their own version of the United States Medal of Honor in October 1862, authorizing President Davis to bestow medals to officers and badges to privates and non-commissioned officers for courage and good conduct. Krasner will describe the democratic manner in which the medals and badges were to be awarded. Due to the shortage of metal, no Confederate Medals of Honor were minted during the Civil War. Instead, in October 1863, the "Roll of Honor" was created to list those officers, non-commissioned officers, and privates deserving of medals and badges, intending to award them at a later date, which never came. In 1900 the United Daughters of the Confederacy introduced their semi-official "Southern Cross of Honor," commonly mistaken as the Confederate "Medal of Honor," to be awarded by the UDC to ex-Confederate soldiers who were members of the United Confederate Veterans in recognition of their devotion to the Southern cause.

August 13, 2014 Program

Janell Bloodworth presented three mini-programs: "The Civil War’s Dirty Laundry," "Lottie Moon – Ambrose Burnside’s Wild and Willful Girlfriend," and "The Most Beloved Song of the Civil War."

The Civil War’s Dirty Laundry

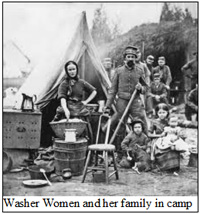

Civil

Was company laundresses continued an army tradition established in 1802.

Thousands served but were scarcely noted in the written records of the

Civil War. Each Union company was allowed four laundresses (one for each

25 soldiers), who served at the pleasure of the company captain and who

received housing, daily rations and the services of the surgeons.

Usually, the laundress was married or related to a soldier in the

company. A laundress’ tent was set apart from the men’s tents, on "Suds

Row." While not "soldiers," laundresses were expected to follow a

semblance of army discipline and were subject to army justice. At least

one was court-martialed for using "disrespectful language." Her sentence

of dismissal was later reversed. Another was accused of trying to murder

her soldier husband with an axe. She said it was only a tin cup, but was

nevertheless drummed out of the regiment and her husband had to take his

dirty clothes elsewhere. A laundress named Hannah O’Neil was "written

up" by Captain Charles P. Adams, of Company H of the 1st Minnesota

Volunteer Infantry, when she burned her tent. Adams refused to replace

Hannah’s tent, so she tore the tent into pieces. Hannah also complained

of inadequate rations. In his report, Adams said Hannah got more rations

than she was entitled to, and accused her of excessive drinking. We

don’t know the end of this story. Union Army Regulations barred "women

of bad character" from the camps, but most laundresses seemed

respectable enough. One private suggested that some of the laundresses

"make lots of money nature’s way."

Civil

Was company laundresses continued an army tradition established in 1802.

Thousands served but were scarcely noted in the written records of the

Civil War. Each Union company was allowed four laundresses (one for each

25 soldiers), who served at the pleasure of the company captain and who

received housing, daily rations and the services of the surgeons.

Usually, the laundress was married or related to a soldier in the

company. A laundress’ tent was set apart from the men’s tents, on "Suds

Row." While not "soldiers," laundresses were expected to follow a

semblance of army discipline and were subject to army justice. At least

one was court-martialed for using "disrespectful language." Her sentence

of dismissal was later reversed. Another was accused of trying to murder

her soldier husband with an axe. She said it was only a tin cup, but was

nevertheless drummed out of the regiment and her husband had to take his

dirty clothes elsewhere. A laundress named Hannah O’Neil was "written

up" by Captain Charles P. Adams, of Company H of the 1st Minnesota

Volunteer Infantry, when she burned her tent. Adams refused to replace

Hannah’s tent, so she tore the tent into pieces. Hannah also complained

of inadequate rations. In his report, Adams said Hannah got more rations

than she was entitled to, and accused her of excessive drinking. We

don’t know the end of this story. Union Army Regulations barred "women

of bad character" from the camps, but most laundresses seemed

respectable enough. One private suggested that some of the laundresses

"make lots of money nature’s way."

Wherever the company went, the laundresses went too, sharing potential hardships and danger. Some officers grumbled about having to transport the laundresses and their equipment, considering them an unnecessary hindrance. One officer wrote, "Transportation of all the laundresses’ paraphernalia, children, dogs, beds, cribs, tables, tubs, buckets, boards and Lord knows what not, amounts to a tremendous item of care and expense. Laundresses, along with hospital nurses, or officers’ servants were specifically exempted from Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s infamous 1862 Special Field Order No 11 banning "all cotton speculators, Jews, and all other vagabonds with no honest means of support, to leave the district . . ." When the Union Army was planning to invade Florida in 1864, it was to travel light, leaving all excess baggage, and its commander, Maj. Gen. Quincy Adams Gilmore, ordered that no females are to accompany or follow the troops "except regularly appointed laundresses, who will be allowed to accompany the baggage of their respective commands."

Life on the road was no pleasure excursion. A laundress needed lots of equipment and supplies: she had to have at least two 25-gallon oak tanks weighing about 35 pounds each empty, plus "buckets, boilers, laundry sticks, scrubboards, soap crates, starch, bluing, ropes, fire grates and basic household items." For her work she usually charged each customer 50 cents a month, but some men did their own wash, some could not afford the cost and some "who wore a garment until it fell apart before giving the vermin a parole and throwing the article away." Considering the labor involved, it’s a wonder that women actively sought the job, but they did. The Federal Military Handbook decreed that a "council of administration" was to set the prices for washing, considering the current prices charged by local civilian laundries and how many officers used their services (who were often charged 2 1/2 times what the soldiers paid). Between her $5 to $7 a month and her husband’s $13 a month, a married couple could do reasonably well. A psychological benefit was that she could stay with her husband rather than endure a long and perhaps permanent separation. The irregularity of visits from the army paymaster, led to "charging" for laundry services, which required that written records be kept by the laundresses, some of whom were illiterate and some of whom took advantage of their "monopoly" to run up bills.

Laundresses provided less tangible services to the men – she often brought along home remedies, often helped the surgeon with his duties, made a home for her husband, and provided other soldiers with hospitality and a welcome reminder of their own homes. On general concluded that having laundresses in camp "tended to make the men more cheerful and comfortable." For many boys in blue the washer woman was a reminder that there was a world beyond the war, where men lived in peace with friends and family. [Adapted from Vickie Wendel, Washer Women, Civil War Times Illustrated (August 1999).

Lottie Moon – Ambrose Burnside’s Wild and Willful Girlfriend

Cynthia

Charlotte "Lottie" Moon was a beauty – dark and petite, with thick brown

hair and eyes that were, appropriately, both gray and blue – whose

beguiling ways attracted many a suitor. She was a wit, a charmer, a

sparkling conversationalist – and always a prankster. An alarming talent

was her ability to throw her jaw out of joint with a cracking sound

while feigning extreme agony. She would put these talents to use as one

of the Confederacy’s most daring and unorthodox spies. Born August 10,

1829, in Danville, Virginia. In 1834, her father, Robert S. Moon, a

descendant of British earls and early settlers of Virginia, decided to

move to Oxford, Ohio, so he could free his slaves. A good shot and

bareback rider, Lottie enjoyed shocking her prim neighbors. A short

stint in Oxford College for Women did not tame her. She accepted Ambrose

Burnside’s proposal but at the altar, when asked if she would love,

cherish and obey him, she said, "No sir-ee Bob I won’t," and fled the

church. All together, she became engaged 12 times, but married James

Clark, who became a brilliant judge. The marriage was not without drama:

Amidst rumors that she would repeat the Burnside fiasco, she challenged

John R. Bond, editor of the Urbana, Ohio, Citizen, "If you get

here before I marry Jim, I’ll marry you." Clark foiled any foolishness

on January 30, 1849, by showing her a small revolver and whispering,

"There will be a wedding tonight or a funeral tomorrow." The first 10

years were tranquil. Lottie bore two sons, first Peter, who died in

infancy, then Frank.

Cynthia

Charlotte "Lottie" Moon was a beauty – dark and petite, with thick brown

hair and eyes that were, appropriately, both gray and blue – whose

beguiling ways attracted many a suitor. She was a wit, a charmer, a

sparkling conversationalist – and always a prankster. An alarming talent

was her ability to throw her jaw out of joint with a cracking sound

while feigning extreme agony. She would put these talents to use as one

of the Confederacy’s most daring and unorthodox spies. Born August 10,

1829, in Danville, Virginia. In 1834, her father, Robert S. Moon, a

descendant of British earls and early settlers of Virginia, decided to

move to Oxford, Ohio, so he could free his slaves. A good shot and

bareback rider, Lottie enjoyed shocking her prim neighbors. A short

stint in Oxford College for Women did not tame her. She accepted Ambrose

Burnside’s proposal but at the altar, when asked if she would love,

cherish and obey him, she said, "No sir-ee Bob I won’t," and fled the

church. All together, she became engaged 12 times, but married James

Clark, who became a brilliant judge. The marriage was not without drama:

Amidst rumors that she would repeat the Burnside fiasco, she challenged

John R. Bond, editor of the Urbana, Ohio, Citizen, "If you get

here before I marry Jim, I’ll marry you." Clark foiled any foolishness

on January 30, 1849, by showing her a small revolver and whispering,

"There will be a wedding tonight or a funeral tomorrow." The first 10

years were tranquil. Lottie bore two sons, first Peter, who died in

infancy, then Frank.

As

war approached, the couple believed in the right of secession and became

the "brains" of the Copperhead movement and supporters of Cong. Clement

L. Vallandigham. Lottie believed "both the planters of the South and the

factories of the North profited from the labor of the slave and the land

of the Indian." Her brothers joined the Confederate Army and Navy. She

took medical supplies across the Ohio river and later campaigned for

improvements in the wretched conditions in Northern prisoner-of-war

prisons. In the summer of 1862, she volunteered to take a message from

one Confederate general to another, which involved crossing from

Cincinnati to Kentucky. She first put on a shabby old shawl and

pretended to be an Irish washerwoman and then conned some Irish troops

into hiding her on a troop transport bound for Lexington, Kentucky.

Eventually she met one C. S. A. Col. Thomas Scott and ordered him to

take her dispatches to Gen. Kirby Smith at once. On her return home, she

overheard a rumor that an order for the arrest of a Southern female spy

had been issued; undaunted she sat on the train from Lexington across

from a noted Kentucky Unionist, pretended to be returning from visiting

"her poor darlin’ husband a-dying" in a Lexington hospital, and,

expressed her fears that she would be "mistaken" for "that spy," and

ended up under his protection across the Ohio River.

As

war approached, the couple believed in the right of secession and became

the "brains" of the Copperhead movement and supporters of Cong. Clement

L. Vallandigham. Lottie believed "both the planters of the South and the

factories of the North profited from the labor of the slave and the land

of the Indian." Her brothers joined the Confederate Army and Navy. She

took medical supplies across the Ohio river and later campaigned for

improvements in the wretched conditions in Northern prisoner-of-war

prisons. In the summer of 1862, she volunteered to take a message from

one Confederate general to another, which involved crossing from

Cincinnati to Kentucky. She first put on a shabby old shawl and

pretended to be an Irish washerwoman and then conned some Irish troops

into hiding her on a troop transport bound for Lexington, Kentucky.

Eventually she met one C. S. A. Col. Thomas Scott and ordered him to

take her dispatches to Gen. Kirby Smith at once. On her return home, she

overheard a rumor that an order for the arrest of a Southern female spy

had been issued; undaunted she sat on the train from Lexington across

from a noted Kentucky Unionist, pretended to be returning from visiting

"her poor darlin’ husband a-dying" in a Lexington hospital, and,

expressed her fears that she would be "mistaken" for "that spy," and

ended up under his protection across the Ohio River.

Her next assignment took her to Canada to pick up a dispatch from the Confederate Knights of the Golden Circle, outlining a possible union between the South and North West against New England and the Federal Government to President Davis. En route, in Washington, D. C., she earned Secretary of War Stanton’s help by pretending to be an English invalid on her way to Warm Springs, Virginia. Stanton even arranged to have her join President Lincoln’s party on its way to Gen. McClellan’s headquarters in Fredericksburg and gave her a pass through the Union lines. When Stanton learned of Lottie’s trick, he offered a $10,000 reward for her capture, dead or alive. Lincoln frequently joked that Stanton’s "sweet babe-like sleep was broken, all a-cause of one woman." One her way North from Richmond, she met a suspicious Union General, F. J. Milroy, who tested her story of being en route to Hot Springs, Arkansas, for relief of her rheumatism by having her examined by his surgeon. During this examination, Lottie popped her jaw with accompanying grinding and cracking noises, and fooled the surgeon. When Lottie reached Cincinnati, she heard that two Southern female spies had been captured and a third was being sought.

She took her act to the General commanding the Army of the Ohio, Ambrose Burnside! Over the 15 years since she had last seen Burnside, Lottie had gained weight, but Burnside immediately recognized her, saying "You have forgotten me, but I have not forgotten the many happy hours I once spent with you in Oxford," and ordered her arrest and trial, a trial that could end with the death penalty. And the other two female Southern spies? None other than Lottie’s sister, Virginia, and mother, Cynthia! [who were in Memphis in 1862 making bandages for the troops when they heard that supplies and messages were needed to be smuggled into Ohio and took on the job. Under suspicion, they were stopped on the train north, but Ginny managed to swallow the secret papers. She could not, however, get rid of the "forty bottles of morphine, seven pounds of opium, and a quantity of camphor" that she had stitched into her clothing and quilts. These were medicinal supplies needed by the Confederate troops. After three months’ spent in comfort, the three women were quietly released. Though "free," all three women were constantly watched and their usefulness to the Confederate cause was ended.

After

the war, Judge Clark and Lottie moved to New York City, where she became

a correspondent for the New York World and was sent to France as

a war correspondent. She also wrote a popular book about the Civil War

under the pen name of Charles M. Clay. The author’s unusual grasp of

politics and economics convinced the public (and Jefferson Davis) that

the author was a man. Lottie finally met an adversary she could not

defeat, dying November 20, 1895, at age 66, in her son’s home in

Philadelphia. After the war, Ginny ended up in Hollywood, appearing in

two movies, "Robin Hood", and "The Spanish Dancer." She later moved to

Greenwich Village, where she died in 1925, at age 81. [Adapted from

Thomas O. And Marlene March, The Ballad of Lottie Moon, in Civil

War, the Magazine of the Civil War Society, December 1989]

After

the war, Judge Clark and Lottie moved to New York City, where she became

a correspondent for the New York World and was sent to France as

a war correspondent. She also wrote a popular book about the Civil War

under the pen name of Charles M. Clay. The author’s unusual grasp of

politics and economics convinced the public (and Jefferson Davis) that

the author was a man. Lottie finally met an adversary she could not

defeat, dying November 20, 1895, at age 66, in her son’s home in

Philadelphia. After the war, Ginny ended up in Hollywood, appearing in

two movies, "Robin Hood", and "The Spanish Dancer." She later moved to

Greenwich Village, where she died in 1925, at age 81. [Adapted from

Thomas O. And Marlene March, The Ballad of Lottie Moon, in Civil

War, the Magazine of the Civil War Society, December 1989]

The Most Beloved Song of the Civil War

December, 1862, after the bloody Battle of Fredericksburg, about

100,000 Federal soldiers and 70,000 Confederate soldiers were camped on

opposite sides of the Rappahannock River. Both sides were still licking

their wounds and planning to revive hostilities. At twilight, the

regimental bands on each side began to play. At times, they competed in

"battles of the bands," trying to drown each other o ut

with patriotic music. At other times, they would take turns. Toward the

end, the music became more poignant and tender. On this night, the

Federal band played the Civil War’s favorite tune and every regimental

band in both armies soon joined in playing "Home Sweet Home." The

soothing notes sent the heartfelt words of the beloved song running

through men’s minds and everyone ceased what they were doing; there

wasn’t a sound except for the music:

ut

with patriotic music. At other times, they would take turns. Toward the

end, the music became more poignant and tender. On this night, the

Federal band played the Civil War’s favorite tune and every regimental

band in both armies soon joined in playing "Home Sweet Home." The

soothing notes sent the heartfelt words of the beloved song running

through men’s minds and everyone ceased what they were doing; there

wasn’t a sound except for the music:

"Mid Pleasures and palaces though we may roam,

Be it ever so humble there’s no place like home!

A charm from the skies seems to hallow us there,

Which, seek through the world, is ne’er met with elsewhere:

Home! Home! sweet, sweet Home!

There’s no place like Home!

There’s no place like Home!"

At the music ended, in the words of Private Frank Mixson, of the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, "Everyone went crazy." Both sides began cheering, jumping up and down and throwing their hats in the air. Had there not been a river between them, reflected Mixson, the two armies would have met face to face, shaken hands, and ended the war on the spot! Fredericksburg wasn’t the only time "Home, Sweet Home" made Billy Yank and Johnny Reb forget they were enemies. Abraham and Mary Lincoln, mourning the loss of their beloved son, Willie, were comforted when the Italian songstress, Adelina Patti, sang it for them in the White House.

On December 31, 1862, on the eve of the Battle of Stones River, a similar scene took place. On May 10, 1864, at Spotsylvania, after the usual contest, when the Confederate band launched into the familiar strains of "Home, Sweet Home," both sides cheered loudly, creating a din never heard before in the hills around Spotsylvania. In the summer of 1864, near Winchester, the pickets agreed not to shoot so the exhausted soldiers could sleep in peace. First the Confederates and then the Federals sang the usual songs. After a while, the sentries on both sides lined up to sing "Home, Sweet Home" and went happily to sleep.

Some Federal officers forbade paying the song, fearing it would make men so homesick they would desert or become too demoralized to fight. The song really had the opposite effect: in reminding them of their loved ones, the song reinforced the basic, personal stake each soldier had in fighting for his side. In that sense, the song had a deeper meaning than a more overtly patriotic song, that appealed to general rather than personal feelings. The urge to protect one’s home and family is more primitive and therefore more immediate

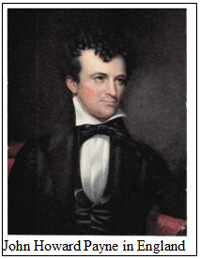

It

is ironic that the words and music to this quintessentially American

song came from an opera, Clari, or The Maid of Milan,

which debuted in London on May 8, 1823! The music was by Henry Bishop

(1786-1855), the most famous English composer of his day, and the lyrics

were by an expatriate American, John Howard Payne (1791-1852), a scion

of an illustrious American family – One cousin was Dolly Payne Madison,

another was Robert Trent Paine, a signer of the Declaration of

Independence. Despite this, Payne was often destitute and lived abroad.

Music critics find the inspiration for Payne’s immortal song in his

longing for his early years with his family in Easthampton, Long Island.

Was this the home he wrote about years later? An actor, at 18, he was

billed as "The American Juvenile Wonder." After his father died and his

career on stage foundered, in 1812 he sailed for England, where he was

initially jailed as a "foreign enemy." Still not successful on stage, he

turned to writing and adapting plays. An English theater manager brought

him a play and convinced him to convert it to an opera. The script

conveyed his sadness that having roamed "mid pleasures and palaces, be

it ever so humble, there was no place like home." The same manager then

convinced Henry Bishop to set Payne’s words to music. The song was a

hit, selling 300,000 copies in its first year. The publisher made

$10,000 profit from the song, but Payne got only $250 and no royalties.

His name did not even appear on the song sheet! Disillusioned, Payne

went back to America, worked as a journalist and fell in love with Maria

Mayo, a beautiful Virginia belle. Sadly, she preferred Winfield S.

Scott. Payne never recovered but was still a celebrity: in 1850, while

performing in Washington, D. C., before President Fillmore, Henry Clay

and Daniel Webster, Jenny Lind sang "Home, Sweet Home" directly to

Payne. When the song ended, Webster, with tears in his eyes, bowed to

Payne. Others followed, giving Payne the greatest ovation in his life.

President Tyler appointed him as Minister to Tunis in1852, where he died

and was buried, forgotten. In 1883, his body was exhumed and arrived in

New York, as a 65-piece band played his famous song. He was buried with

full honors in Oakhill Cemetery, outside Washington, D. C., on June 9,

1883. The author of the Civil War’s most beloved song had finally come

home to rest. [Adapted from Ernest L. Abel, John Howard Payne’s

haunting ‘Home, Sweet Home," was the Civil War Soldier’s favorite song,

in America’s Civil War, May 1996]

It

is ironic that the words and music to this quintessentially American

song came from an opera, Clari, or The Maid of Milan,

which debuted in London on May 8, 1823! The music was by Henry Bishop

(1786-1855), the most famous English composer of his day, and the lyrics

were by an expatriate American, John Howard Payne (1791-1852), a scion

of an illustrious American family – One cousin was Dolly Payne Madison,

another was Robert Trent Paine, a signer of the Declaration of

Independence. Despite this, Payne was often destitute and lived abroad.

Music critics find the inspiration for Payne’s immortal song in his

longing for his early years with his family in Easthampton, Long Island.

Was this the home he wrote about years later? An actor, at 18, he was

billed as "The American Juvenile Wonder." After his father died and his

career on stage foundered, in 1812 he sailed for England, where he was

initially jailed as a "foreign enemy." Still not successful on stage, he

turned to writing and adapting plays. An English theater manager brought

him a play and convinced him to convert it to an opera. The script

conveyed his sadness that having roamed "mid pleasures and palaces, be

it ever so humble, there was no place like home." The same manager then

convinced Henry Bishop to set Payne’s words to music. The song was a

hit, selling 300,000 copies in its first year. The publisher made

$10,000 profit from the song, but Payne got only $250 and no royalties.

His name did not even appear on the song sheet! Disillusioned, Payne

went back to America, worked as a journalist and fell in love with Maria

Mayo, a beautiful Virginia belle. Sadly, she preferred Winfield S.

Scott. Payne never recovered but was still a celebrity: in 1850, while

performing in Washington, D. C., before President Fillmore, Henry Clay

and Daniel Webster, Jenny Lind sang "Home, Sweet Home" directly to

Payne. When the song ended, Webster, with tears in his eyes, bowed to

Payne. Others followed, giving Payne the greatest ovation in his life.

President Tyler appointed him as Minister to Tunis in1852, where he died

and was buried, forgotten. In 1883, his body was exhumed and arrived in

New York, as a 65-piece band played his famous song. He was buried with

full honors in Oakhill Cemetery, outside Washington, D. C., on June 9,

1883. The author of the Civil War’s most beloved song had finally come

home to rest. [Adapted from Ernest L. Abel, John Howard Payne’s

haunting ‘Home, Sweet Home," was the Civil War Soldier’s favorite song,

in America’s Civil War, May 1996]

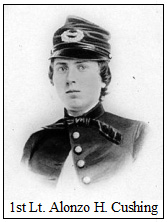

ABC

News: It has taken more than 150 years, but a heroic Union Army officer

who died at the Battle of Gettysburg is being awarded the nation's

highest military honor by President Barack Obama. First Lieutenant

Alonzo H. Cushing, 22, was killed in action on July 3, 1863, the

battle's third and final day. His death occurred defending against

Pickett's Charge, an ultimately futile Confederate advance. Cushing

served as commanding officer of Battery A, 4th United States Artillery

Brigade, 2nd Corps, Army of the Potomac. During the battle, Cushing's

battery took a severe pounding from the Confederate artillery, and

Cushing was wounded in the stomach and right shoulder Despite his

injuries, Cushing refused to leave the battlefield, commanding his men

and defending his position on Cemetery Ridge against the charging

opposition. Cushing's efforts helped the Union Army to fight off the

Confederate attack – with the South forced to retreat, sustaining

massive losses. The South would never advance that far north again, a

flash-point in the Union's victory.

ABC

News: It has taken more than 150 years, but a heroic Union Army officer

who died at the Battle of Gettysburg is being awarded the nation's

highest military honor by President Barack Obama. First Lieutenant

Alonzo H. Cushing, 22, was killed in action on July 3, 1863, the

battle's third and final day. His death occurred defending against

Pickett's Charge, an ultimately futile Confederate advance. Cushing

served as commanding officer of Battery A, 4th United States Artillery

Brigade, 2nd Corps, Army of the Potomac. During the battle, Cushing's

battery took a severe pounding from the Confederate artillery, and

Cushing was wounded in the stomach and right shoulder Despite his

injuries, Cushing refused to leave the battlefield, commanding his men

and defending his position on Cemetery Ridge against the charging

opposition. Cushing's efforts helped the Union Army to fight off the

Confederate attack – with the South forced to retreat, sustaining

massive losses. The South would never advance that far north again, a

flash-point in the Union's victory.

From the Waukesha Freeman (Wisconsin) in 1911: "The Confederate cannon sent volleys over the heads of their advancing troops into the Union lines. Cushing and his neighbors replied with never ceasing spirit, in spite of a constant rain of shot and shell, with horses and men falling all around." "Cushing was shot several times but kept on firing. He served his last round of canister, was struck in the mouth by a bullet and fell dead." Despite a marker erected to Cushing on Cemetery Ridge and a monument near his birthplace, the Medal of Honor eluded him. Descendants and Civil War buffs took up the cause in recent decades. Congress granted a special exemption last December for Cushing to receive the award posthumously since recommendations normally have to be made within two years of the act of heroism and the medal awarded within three years. Cushing has endured a longer wait than any of the 3,468 recipients to receive the Medal of Honor. His Medal of Honor will be awarded on Sept. 15.

Last changed: 09/04/14