The President’s Message:

The first meeting of the Civil war Round

Table of the Palm Beaches officially was held on September 16, 1987.

The attendance sheet listed

Robert Godwin, Rodney Dillon, Dr. Joel Gordon, and Greg Parkinson.

Robert Godwin fulfilled his dream

of gathering together like individuals who wanted to discuss and study

the Civil War. I hope that Bob

Godwin is looking down at us and pleased that the Round Table will be

celebrating our twenty-ninth anniversary.

The Round Table meeting is canceled for Wednesday,

October

12, 2016.

This year Yom Kippur falls on the day of the Round Table meeting in

October. A suitable,

alternative date was not available at the Scottish Rite Hall.

Robert Krasner will be speaking

in November.

A very special thank you goes to the officers

and members who have served the Round Table through the years.

Your continued support helps to

make the Club even stronger.

Anyone who volunteers, even for the smallest task, adds to the success

of our organization. Your efforts

are always appreciated.

We will have some special books in the

raffle. The refreshments will be

cakes baked from Civil War recipes, one from the North and one from the

South.

Happy Anniversary, Round Table!

Gerridine LaRovere

September 14, 2016 Program:

The Round Table meeting on September 14, 2016

will be a panel discussion of what was going on in the world from 1845 -

1870. The panel will be made up of our members with each one

giving a 10 -15 summary of a particular country. Countries to

include Spain, England, Germany, Mexico, China, Russia, and France.

August 10, 2016 Program:

William

McEachern spoke on the topic

Robert E. Lee's Real

Plan at Gettysburg.

What was Robert E. Lee’s Plan for Gettysburg on July 3, 1863?

To answer this question, one has to try to ascertain what was in

the mind of Robert E. Lee during the three days of July of 1863.

How can one do this?

We shall review the Official Reports written by Lee himself, as well as

any other writings that Lee made dealing with this issue.

We shall review the battle itself to see if such a review can

provide clues as to what Lee’s real plan was.

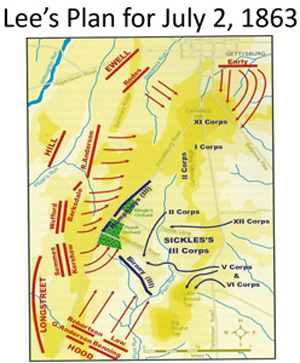

This will entail reviewing maps of the battle on all three days.

Next, we shall review letters, diaries, and reports of

Confederate officers who reported what they were told by Lee and what

they told Lee. Finally, we

shall review what Union officers and soldiers wrote about the battle. William

McEachern spoke on the topic

Robert E. Lee's Real

Plan at Gettysburg.

What was Robert E. Lee’s Plan for Gettysburg on July 3, 1863?

To answer this question, one has to try to ascertain what was in

the mind of Robert E. Lee during the three days of July of 1863.

How can one do this?

We shall review the Official Reports written by Lee himself, as well as

any other writings that Lee made dealing with this issue.

We shall review the battle itself to see if such a review can

provide clues as to what Lee’s real plan was.

This will entail reviewing maps of the battle on all three days.

Next, we shall review letters, diaries, and reports of

Confederate officers who reported what they were told by Lee and what

they told Lee. Finally, we

shall review what Union officers and soldiers wrote about the battle.

The traditional approach to Lee’s

plan may be summarized as follows: Lee tried the Union right flank on

the 1st, the Union right and left flanks on

the 2nd, and the Union center on the 3rd.

This analysis overlooks the fact that Robert E. Lee said that the

plan was unchanged from the 2nd to the 3rd.

How can an attack on the center be the same as an attack on the

left flank?

The traditional approach to Lee’s

plan basically holds that Lee took an opportunistic approach.

Lee’s Army stumbled into the Union Army on July 1, 1863.

Lee ordered Ewell to assault Cemetery Ridge, because it was their

and it was the logical follow-up to what had already happened in July 1st.

On July 2nd, 1863, Lee tried attacking the

other flank, as well as trying to attack the northern flank of the Union

army. On July 3rd, 1863, Lee attacked the center,

because, having tried both flanks, Lee thought the center must be weak.

The traditional analysis puts a

great deal of emphasis upon Little Round Top on the 2nd.

Thus, the traditional analysis argues that Lee recognized Little

Round Top as being the key geographical position and, therefore, had

Longstreet make his assault against it.

For the traditional analysis to be

correct, Lee’s official reports would have to have mentioned Little

Round Top in some way.

Unfortunately, Lee does not mention Little Round Top by name or in any

other way in any of his three reports.

On the other hand, Cemetery Ridge and Cemetery Hill figure quite

largely in Lee’s reports.

How can the traditional analysis be correct, if Lee does not recognize

Little Round Top as being the key?

Did Lee’s plan change?

Lee certainly did not think so.

Lee issued two Official Reports of the battle.

In each of these Official Reports, Lee wrote that his plan was

unchanged from the 2nd to the 3rd.

On July 31, 1863, Robert E. Lee wrote his first official report

concerning the Battle of Gettysburg.

Lee wrote: “These

partial successes determined me to continue the assault next day (NB:

the 3rd).

Pickett, with three of his brigades, joined Longstreet for the

following morning, and our batteries were moved forward to the positions

gained by him the day before.

The general plan of

attack was unchanged

excepting that one division and two

brigades of Hill's corps were ordered to support Longstreet.”

Further, months later, Lee forwarded

to Richmond his Official Report of the Battle of Gettysburg, dated

January __, 1864: “The result of this day's operations (NB: July 2nd, 1863)

induced the belief that, with proper concert of action, and with the

increased support that the positions gained on the (NB Confederate)

right would enable the artillery to render the assaulting columns, we

should ultimately succeed, and it was accordingly determined to continue

the attack.

The general plan was unchanged.

Of particular note is the fact that

Lee not only said on July 31, 1863 that the plan was unchanged, but also

he reiterated that statement six months later in the January __, 1864

Report. If Lee changed the

plan from a flank attack on the left on July 2nd 1863 to an attack on the center on

July 3rd, 1863, why didn’t he say so?

He certainly had plenty of time to think over his statement in

the intervening six months.

The fact that he did not do so emphasizes that fact that the plan was

the same. So, we have to

look under the hood and see what the point of the attacks on each day of

July were to see what the real plan was.

A superficial analysis will not suffice.

What was his plan, then?

The plan had at least four elements: 1) attack a salient; 2)

concentration of a large portion of Confederate forces upon a small

portion of the Union forces; 3) concentration at the commanding

geographical position held by the Union forces; and 4) gaining that

geographical position to destroy the Union Army and win the ‘war in a

day’.

I believe that Lee’s Plan was always

to assail the Union Army on Cemetery Hill and Ridge.

What supports this analysis?

On July 2nd, Lee wanted to take a certain

commanding position on the Union left.

“In front of General Longstreet the enemy held a position from

which, if he could be driven, it was thought our artillery could be used

to advantage in assailing the more elevated ground beyond, and thus

enable us to reach the crest of the ridge.

That officer was directed to endeavor to carry this position…”

This position is the Peach Orchard.

We know this because Porter Alexander identified it as such for

us.

“The enemy occupied a strong

position, with his right upon two commanding elevations adjacent to each

other, one southeast, and the other, known as Cemetery Hill, immediately

south of the town, which lay at its base.”

Interestingly enough, Cemetery Hill is the only terrain feature,

other than the Emmitsburg Road, which is mentioned in the Official

Reports of Ewell, Hill, and Longstreet.

Lee mentions the features of Cemetery Ridge and the Emmitsburg

Road. Note that he does not

mention Little Round Top by name and does not think it important.

If Little Round Top were the position that Lee sought to gain as

the most important position to defeat the Union Army, why doesn’t is

figure into his Official Reports.

Why Would Lee Target Cemetery Hill?

First, the road network converges at the north edge of Cemetery

Hill. Second, the height of

Cemetery Hill is only a few feet shorter than Culps Hill; it is taller

than Brenner’s Hill; it is much higher than Cemetery Ridge.

It was far clearer of trees and shrubbery in 1863, so it made an

ideal gun platform in all directions.

Third, on the other hand, it was, in essence, a salient, which is

a militarily weak position.

Fourth, it was the position to which the Union Army had fled on July 1,

1863. Fifth, the Union Army

holding Cemetery Hill threatened Lee’s ability to move forces around

from Seminary Ridge to east

of Cemetery Hill.

On July 1st, at around 5:00pm, Longstreet

reported that he found Lee on Seminary Ridge watching the enemy retreat

to Cemetery Hill. Longstreet

wrote, “He [Lee] pointed out their position to me.”

This is when Longstreet discussed with Lee Longstreet’s plan to

shift the battle south and to march around the Union’s left flank.

After Longstreet presented his plan, Lee disagreed, “No, the

enemy is there, and I am going to attack him there.”

At that time, while the Union retreat was going on, the only

place to which the word ‘there’ could apply was Cemetery Hill, because

it was the only position the Union occupied.

On the evening of July 1st, Lee met with Generals Ewell,

Early, and Rodes. During

this meeting Lee discussed the possibility of a direct, frontal assault

upon Cemetery Hill. Ewell

demurred saying, “Cemetery Hill and the rugged hills on the left of

it…would inevitably be [taken only] at very great loss.”

In response to this, Lee suggested then that Ewell’s corps be

brought to the west. Ewell

responded negatively to this suggestion and replied that Cemetery Hill

could be taken “…as soon as Longstreet had broken the lines of the

Federal left.” Ewell argued

that Cemetery Hill was assailable from the Confederate right.

To answer why Lee attacked July 2,

1863, we need to know more about what Lee knew at the time of planning

the attack. The first

question then is what reconnaissance was done.

At about 4:00 am on July 2nd, 1863, Lee sent Captain Samuel R.

Johnston, a topographical engineer of Lee’s staff, out on a

reconnaissance mission to investigate the Union left flank.

While there is uncertainty of how far east Captain Johnston got,

there is no doubt that he reached the Peach Orchard.

What Captain Johnson told Lee, whether it was accurate or not is

not the issue, is that there were no Union forces in the Peach Orchard,

or on Houck’s Ridge, Big Round Top, and Little Round Top.

Thus, Lee formulated his plans in the belief that there were

Union forces south of some point on Cemetery Ridge, as he and his

generals had observed the previous evening.

Here is what Lee

ordered: Longstreet was

ordered to take the ground to his front in order to gain an artillery

position, i.e. the Peach Orchard.

It is clear that Little Round Top was not part of the plan.

Under this order, Hill is to threaten the enemy’s center and to

cooperate with Longstreet’s attack.

If Longstreet was ordered to attack Little Round Top, then

Longstreet would be marching east away from Hill and, thereby,

stretching Hill further and further from the Union center.

In a letter to Longstreet written after the war, Hood wrote that

Longstreet ordered Hood three times to attack “… up the Emmitsburg

Road.” Going up the

Emmitsburg Road

does not go to Little Round Top, but

rather goes northeast towards Cemetery Hill.

Ewell

was ordered to take Cemetery Hill, the high ground on the Union right.

He was further instructed to make a simultaneous demonstration

upon the enemy's right, to be converted into a real attack should

opportunity offer. Ewell

was ordered to take Cemetery Hill, the high ground on the Union right.

He was further instructed to make a simultaneous demonstration

upon the enemy's right, to be converted into a real attack should

opportunity offer.

First major conclusion:

Lee’s plan for July 2, 1863 was not to attack Little Round Top,

but to find a way to attack Cemetery Hill.

Longstreet’s attack was to gain the Peach Orchard to be used as a

gun platform. Little Round

Top could not be that gun platform, for while it was de-forested on the

western side, it was not deforested on the north side.

Thus, artillery on Little Round Top could not bear down the axis

of the Union line stretching north.

Further, Little Round Top was so rugged that very few guns could

be brought to its summit.

So, even if Little Round Top were gained, it was not a very good gun

platform for what Lee wanted to do.

The Peach orchard on the other hand had room enough for multiple

batteries and did allow for firing in a converging fire manner upon

Cemetery Hill.

In my opinion, Lee was trying on

July 2nd, 1863 to replicate what he had done

time and time again: a division of his army in the face of the enemy

combined with a march to hit a flank of the enemy with the aim of

re-concentrating at the point of military importance.

Lee had used this tactic most recently at Chancellorsville.

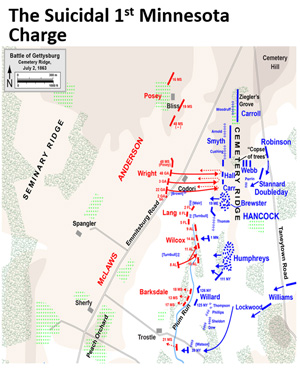

On Lee’s right he ordered Longstreet and Hill to utilize an “en

echelon” attack against the Union forces.

This one at a time attack along a diagonal had Hood’s brigades

going in first, followed by McLaws, and the Anderson.

It was very successful.

Of particular note was McLaws’ division of Longstreet’s corps

attack in the late afternoon on at least two sides of the Peach Orchard.

All Union resistance there collapsed.

At this time, Longstreet ordered Porter Alexander to bring

forward a full battalion of artillery-six batteries-to the Peach Orchard

as this was the plan to shell Union positions.

The entire Union left was caving in.

Humphreys, the Union officer in charge of this sector, looked at

his three disintegrating brigades and the entire Union line that was

evaporating under the Confederate charge and later wrote.

“For the moment, I thought the day was lost.”

Barksdale, obeying his original orders, wheeled his troops

northeast, parallel to the Emmitsburg Road, and ordered them to charge.

The 1st Minnesota held the Union line at a terrible cost.

Barksdale himself was killed at the apex of his advance.

Darkness, as well as Confederate exhaustion, finally ended the

day’s fight as the shaken, depleted Federal units on their heights took

stock. They had barely held

on against the full ferocity of the Rebels, on a day that decided the

fate of the nation.

The

situation was so crucial atop Cemetery Hill, that Major General Winfield

S. Hancock personally ordered Randall of the 13th Vermont to save the guns.

Randall answered Hancock’s plea to retake the guns with, “I can

and damn quick too, if you will let me.”

It is important to note that Hancock said that had he not ordered

this suicided attack, then the day “would have been lost’, not the day

“could have been lost.” The

situation was so crucial atop Cemetery Hill, that Major General Winfield

S. Hancock personally ordered Randall of the 13th Vermont to save the guns.

Randall answered Hancock’s plea to retake the guns with, “I can

and damn quick too, if you will let me.”

It is important to note that Hancock said that had he not ordered

this suicided attack, then the day “would have been lost’, not the day

“could have been lost.”

Note the timing of the Cemetery Hill

attacks on July 2nd, 1863.

Long after the attacks on Cemetery Ridge ended, Ewell gets his

troops into action. The same

troops that had just defended the Ridge make it back in time to defend

the Hill.

Just as twilight

was bringing an end to the fighting on the Union left, Confederate Gen.

Richard S. Ewell's assault on the opposite flank was about to commence.

A half an hour before sunset, the division of Gen. Edward

"Allegheny" Johnson began its long charge up the steep slopes of Culp's

Hill. Opposing Johnson's

4,700 Confederates, roughly 1,600 New Yorkers under Gen. George Sears

Greene were charged with holding the extreme right flank of the Union

Army and protecting its supply line, the Baltimore Pike.

Under the light of a full moon, Johnson's men made their assault,

only to run headlong into formidable breastworks erected by Greene's

troops. Gen. Maryland

Steuart's brigade managed to outflank the Yankees, who merely fell back

to another line or breastworks.

Increasing darkness led to great confusion as both sides tried to

blindly feed reinforcements into the fight.

The battle for Culp's Hill would resume at daylight.

In Lee’s two official

reports, Lee talks of the successes on July 2nd as a reason to go

forward on July 3rd.

In particular, Lee cites the capture of commanding position on

July 2nd as inducement to go

forward on July 3rd.

“…and with the

increased support that the positions gained on the right would enable

the artillery to render the assaulting columns, we should ultimately succeed…”

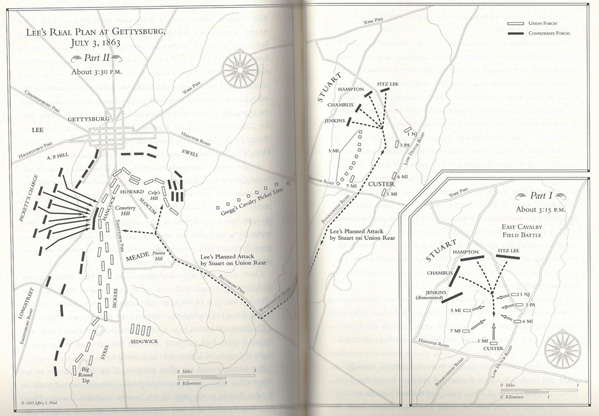

Stuart arrived at Gettysburg at

between noon and 1:00pm on the 2nd and immediately reported to Lee.

On the afternoon of July 2, 1863, Stuart rode off with a small

cadre of horseman when he heard the firefight between Fitz Lee’s

troopers and the 10th NY on Brinkerhoff Ridge.

Several commentators have stated that Lee gave no orders to

Stuart for July 3, 1863.

This statement is patently contradicted by Stuart’s official Report.

Lee wanted Stuart to guard Ewell’s left flank and attack the

Union rear when Ewell’s advance was successful.

Although

Stuart wrote that he intended to effect a surprise upon the Union Army,

this surprise was not affected.

“I moved this command and W. H. F. Lee's secretly through the

woods to a position, and hoped to effect a surprise upon the enemy's

rear, but Hampton's and Fitz.

Lee's brigades, which had been ordered to follow me,

unfortunately debouched into the open ground, disclosing the movement,

and causing a corresponding movement of a large force of the enemy's

cavalry.” Stuart’s Official

Report blames Hampton and Fitz Lee for spoiling the surprise.

Yet two things undermined this assertion.

First, Stuart did not disguise his movement, because it was seen

by Howard’s XI Corps of Cemetery Hill.

This movement alerted Pleasanton, who may have in turn alerted

Gregg according to Gregg’s Official Report, which has to be called into

question, because he barely mentions Custer and seems to say that all

the casualties on the 3rd came from his troopers, when in fact 86% of the casualties came from

Custer’s men. In addition,

when Stuart reached Cress Ridge at around noon, he had his artillery

unlimber and then it fired either 2 shots or four, depending upon the

source, for reasons unstated.

Did Stuart ruin his own surprise? Although

Stuart wrote that he intended to effect a surprise upon the Union Army,

this surprise was not affected.

“I moved this command and W. H. F. Lee's secretly through the

woods to a position, and hoped to effect a surprise upon the enemy's

rear, but Hampton's and Fitz.

Lee's brigades, which had been ordered to follow me,

unfortunately debouched into the open ground, disclosing the movement,

and causing a corresponding movement of a large force of the enemy's

cavalry.” Stuart’s Official

Report blames Hampton and Fitz Lee for spoiling the surprise.

Yet two things undermined this assertion.

First, Stuart did not disguise his movement, because it was seen

by Howard’s XI Corps of Cemetery Hill.

This movement alerted Pleasanton, who may have in turn alerted

Gregg according to Gregg’s Official Report, which has to be called into

question, because he barely mentions Custer and seems to say that all

the casualties on the 3rd came from his troopers, when in fact 86% of the casualties came from

Custer’s men. In addition,

when Stuart reached Cress Ridge at around noon, he had his artillery

unlimber and then it fired either 2 shots or four, depending upon the

source, for reasons unstated.

Did Stuart ruin his own surprise?

Stuart was in the right place at the right time, if the

Confederates achieved a break through on Cemetery Ridge to isolate and

destroy Cemetery Hill.

On July 3rd, Stuart and his men engaged in a

bloody battle with Union cavalry forces.

General George A. Custer of David Gregg’s command fought at what

has become known as East Cavalry Field.

The battle began with a cavalry charge from the Confederate

forces, which was countered by the 7th Michigan.

The two forces engaged in intense point-blank fighting along the

fences of Rummel Farm. In

effort to turn the tides in his favor, Stuart sent a second charge led

by Wade Hampton, during which Hampton received multiple slashes to his

face at the hands of Union sabers.

Eventually, Union forces were able to surround the Confederates

on three sides, forcing Stuart to withdraw due in no small measure to

the Spencer repeating rifle.

But the Union men were in no condition to pursue them further as they

were still outnumbered. The

withdrawal at East Cavalry Field brought an end to Stuart’s troubled

ride to Gettysburg.

This was certainly Custer’s finest

hour. He had been ordered to

leave this area, but he recognized its importance.

He stayed behind, disobeying orders, until he met Gregg and

convinced him it was necessary that he, Custer, should remain.

During the battle, Custer charge superior numbers of Confederates

and drove them back.

This takes us to the fateful day of

July 3, 1863. Lee believes,

as I have explained, that he was successful on the 2nd.

The plan continued to be to take Cemetery Hill.

His failure on the 3rd was due to a number of factors.

First, there was a lack of co-operation and concentration of

forces. Next was Ewell being

taken out of equation by spoiler attack by Union on morning of July 3rd.

This was followed by Custer’s victory over Stuart.

There was no 2nd wave not supporting Pickett’s

Charge. And finally, the

artillery did not support Pickett’s flanks nor did it take out the Union

artillery. General George

Pickett had a few choice words for the day:

“The Yankees had something to do with it.”

Last changed: 08/24/16

Home

About News

Newsletters

Calendar

Memories

Links Join

|