Volume

26, No. 10 – October 2013 Volume

26, No. 10 – October 2013

Volume 26, No. 10

Editor: Stephen L. Seftenberg

Website:

www.CivilWarRoundTablePalmBeach.org

President's Message

On Wednesday, November 6, 2013 at 11 AM, in the World Performing Arts

Center of Lynn University, an old friend of the Round Table, Robert

Watson, will discuss the many faces of Lincoln and the 150th anniversary

of the Emancipation Proclamation and the Gettysburg Address. This is a

free event.

October 9, 2013 Program

The speaker for this meeting will be Richard Adams. His subject will

be: West Point Class of 1861. This is the subject of his

book: The Parting. This book is a research-based story

about a true “band of brothers,” the West Point Class of 1861 (numbering

fifty, and a microcosm of the nation) on the eve of the Civil War and

experiencing their last year at the Academy. As the country unravels and

another is formed, best friends are forced to make choices that will pit

them against each other in war. With few exceptions, the story

characters are real and their deeds part of recorded history.

September 11, 2013 Program

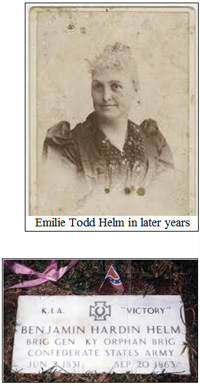

Janell Bloodworth: "Emilie Todd Helm, Abraham

Lincoln’s Confederate Sister-in-Law"

Janell quoted liberally from Maggie MacLean’s Civil War Women Blog:

Emilie Todd Helm, Mary Todd Lincoln’s half-sister, was invited to the

White House in 1863, after the death of her husband, Confederate General

Benjamin Hardin Helm, in the Battle of Chickamauga.

Emilie

was born November 11, 1836, to Robert Smith Todd and Elizabeth Humphreys

Todd of Lexington, Kentucky. She was born into a wealthy family with

exceptional advantages in both education and culture, which was afforded

to few ladies of her time. Emilie was 18 years younger than Mary. Robert

Todd was a prominent Lexington banker and patriarch of a growing brood.

He had seven children with his first wife, Eliza Ann Parker, on of whom

was Mary Todd Lincoln. Emilie was part of his "second family," the eight

children whom he fathered with Elizabeth. Most of the children from

Robert Todd’s second marriage sided with the Confederacy. In 1846, when

Emilie was ten, Mary arrived in Lexington with her husband, Abraham

Lincoln, an Illinois lawyer and rising member of the Whig party. Lincoln

has just been elected to Congress and they were on their way to

Washington, DC. Little Emilie was scared of Lincoln at first, a towering

figure in a long coat and black fur cap. As the adults chatted, Emilie

hid behind her mother’s skirts. Lincoln saw her, smiled and swept her up

into his arms, "So this is little sister!" From that day on, he called

her Little Sister. Emilie was considered the prettiest Todd

sister. She was petite, with raven-black hair and appealingly large

eyes. Emilie’s beauty, poise and charm made her the ideal Southern

belle. Emilie

was born November 11, 1836, to Robert Smith Todd and Elizabeth Humphreys

Todd of Lexington, Kentucky. She was born into a wealthy family with

exceptional advantages in both education and culture, which was afforded

to few ladies of her time. Emilie was 18 years younger than Mary. Robert

Todd was a prominent Lexington banker and patriarch of a growing brood.

He had seven children with his first wife, Eliza Ann Parker, on of whom

was Mary Todd Lincoln. Emilie was part of his "second family," the eight

children whom he fathered with Elizabeth. Most of the children from

Robert Todd’s second marriage sided with the Confederacy. In 1846, when

Emilie was ten, Mary arrived in Lexington with her husband, Abraham

Lincoln, an Illinois lawyer and rising member of the Whig party. Lincoln

has just been elected to Congress and they were on their way to

Washington, DC. Little Emilie was scared of Lincoln at first, a towering

figure in a long coat and black fur cap. As the adults chatted, Emilie

hid behind her mother’s skirts. Lincoln saw her, smiled and swept her up

into his arms, "So this is little sister!" From that day on, he called

her Little Sister. Emilie was considered the prettiest Todd

sister. She was petite, with raven-black hair and appealingly large

eyes. Emilie’s beauty, poise and charm made her the ideal Southern

belle.

Benjamin Hardin Helm was born June 2, 1831, in Elizabethtown,

Kentucky, the son of Lucinda Barbour Hardin and John Lane Helm, two-term Governor of Kentucky.

Benjamin was the first of 12 children. He attended the Kentucky Military

Institute and the U. S. Military Academy at West Point, New York,

graduating ninth in a class of 42 cadets in 1851. Hardin was appointed

Brevet Second Lieutenant in the 2nd U. S. Dragoons, but resigned his

commission the following year due to illness, after serving at a cavalry

school at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and at Fort Lincoln, Texas. Helm then

studied law, first at the University of Louisville, where he graduated

in 1853 and later at Harvard. He practiced law in Elizabethtown, was

elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives in 1855, and became

States’ Attorney for the Third District of Kentucky. In 1860, he became

an Assistant Inspector General in the Kentucky State Guard.

Barbour Hardin and John Lane Helm, two-term Governor of Kentucky.

Benjamin was the first of 12 children. He attended the Kentucky Military

Institute and the U. S. Military Academy at West Point, New York,

graduating ninth in a class of 42 cadets in 1851. Hardin was appointed

Brevet Second Lieutenant in the 2nd U. S. Dragoons, but resigned his

commission the following year due to illness, after serving at a cavalry

school at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and at Fort Lincoln, Texas. Helm then

studied law, first at the University of Louisville, where he graduated

in 1853 and later at Harvard. He practiced law in Elizabethtown, was

elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives in 1855, and became

States’ Attorney for the Third District of Kentucky. In 1860, he became

an Assistant Inspector General in the Kentucky State Guard.

Emilie married Benjamin in 1856. They had three children: Katherine

(1857-1937), who never married, became a well-known artist who painted

many portraits of the family and of notable personalities. She painted

six portraits of Mary Todd Lincoln, one of which now hangs in the White

House. She also wrote, The True Story of Mary, Wife of Abraham.

Elodie (1859-1953), married Waller Lewis but had no children. Benjamin

Hardin Helm, Jr. (1862-1946) never married. When the Helms visited the

Lincolns in the late 1850s, Lincoln took a liking to the younger man,

whom he called "Ben," despite their deep political differences. When the

Southern states seceded, Kentucky tried to stay remained neutral: Even

though it was a slave state and Southern in culture, it also had strong

Unionist sentiment, thanks to the nationalist traditions of famous

Kentuckians like Henry Clay. Some joined the South and some stayed with

the Union.

President Lincoln offered Helm an officer’s commission in the Union

army, but Helm declined. Instead he returned to Kentucky and helped

recruit the 1st Kentucky Cavalry Regiment, CSA. Helm was commissioned a

colonel on October 19, 1861. Under Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner, he

occupied Bowling Green, Kentucky. Promoted to Brigadier General March

14, 1862, and was posted to Vicksburg, under Maj. Gen. John C.

Breckinridge, who led an expedition to Baton Rouge. Helm missed the

battle because of injuries from a fall off his horse. Four of Emilie’s

and Mary’s brothers fought for the Confederacy: David Todd, George

Rogers Clark Todd (a skilled surgeon and the only son of Robert Todd to

side with the South), Samuel Todd (killed at Shiloh April 1862) and

Alexander Todd (served as an aide to Helm; killed by friendly fire

August 1862).

Emilie followed her husband as the war progressed. In Chattanooga,

she organized better care for wounded soldiers. In early 1863, Helm was

put in command of the First Kentucky Brigade, which was nicknamed the

"Orphan Brigade," probably because the soldiers could not return to

their union-held homes during the war. On September 20, 1863, Helm was

mortally wounded leading a futile charge against strong Union

entrenchments in the Battle of Chickamauga. Helm asked the doctor if

there was any hope and was told there was none. As the sounds of battle

faded, he roused himself to ask the outcome. On being told that the army

had triumphed, he uttered, in a pained whisper, "Victory." Helm’s

passing was felt not only throughout Kentucky and the South, but sadness

also settled over the White House. Lincoln was deeply moved and told a

member of his cabinet that he felt like David in the Bible when he

learned his son, Absalom, had been killed. Abraham and Mary went into

private mourning, knowing "that a single tear shed for a dead enemy

would bring torrents of scorn and bitter abuse on both of them."

Emilie accepted an offer to visit the Lincolns in late 1863. She

passed through the Union lines in December 1863, accompanied by her

daughter, Katherine, despite Emilie’s refusal to attest to her loyalty

to the Union while temporarily detained in Fort Monroe, Virginia. Emilie

noted in her diary,

"Mr. Lincoln and my sister met me with the warmest affection, we

were all too grief-stricken at first for speech. I have lost my

husband, they have lost their fine little son, Willie. Mary and I

have lost three brothers in the Confederate service. We could only

embrace each other in silence and tears. Our tears gathered silently

and fell unheeded as with choking voices we tried to talk of

immaterial things."

There were lighter moments as well. Emilie’s daughter, Katherine, and

the Lincolns’ son, Tad, argued over whether the President was Abraham

Lincoln or Jefferson Davis. The Lincolns had a special fondness for

Emilie. While in Washington, however, she kept a very low profile.

Nevertheless, she was labeled "the Rebel in the White House," and

her stay caused a furor in the Northern press. When Gen. Daniel Sickles

baited Emilie by saying, "We have whipped the rebels at Chattanooga and

I hear the scoundrels ran like scared rabbits," Emilie responded, "It

was the example you set for them at Bull Run and Manassas." When Sickles

protested Emilie’s presence in the White House, Lincoln responded,

"General Sickles, my wife and I are in the habit of choosing our own

guests. We do not need from friends either advice or assistance in the

matter." Emilie soon left. Using the word, Confederate, which he

rarely wrote or spoke, Lincoln wrote the following pass (omitting

mention that Emilie had not taken an oath of loyalty to the Union):

"To whom it may concern: It is my wish that Mrs. Emilie T. Helm

(widow of the late General B. H. Helm, who fell in the Confederate

service), now returning to Kentucky, may have protection of person

and property, except as to slaves, of which I say nothing." A.

Lincoln.

Emilie found Lexington under Federal martial law and very hostile to

those who would not take an oath of loyalty to the Union. Shortly

thereafter, Emilie wrote to Lincoln, asking him to send clothing to

Confederate prisoners at Camp Douglas, outside Chicago. She concluded

the letter, "I hope am not intruding too much upon your kindness and

will try not to overstep the limits that I should keep." Later, when

Emilie sought permission to travel into the Confederacy to sell some

cotton, Lincoln declined. He had already gone out on a limb by giving

her an amnesty paper without her taking a loyalty oath. In August 1864,

he wrote the following order to the Union military commander in

Kentucky:

"Last December, Mrs. Emily T. Helm, half-sister to Mrs. Lincoln,

and widow of the rebel General Ben Hardin Helm, stopped here on her

way from Georgia to Kentucky, and I gave her a paper, as I remember,

to protect her against the mere fact of her being General Helm’s

widow. I hear a rumor today that you recently sought to arrest here,

but was prevented by her presenting the paper from me. I do not

intend to protect her against the consequences of disloyal words or

acts. It is hereby revoked, pro tanto. Deal with her for

current conduct just as you would with any other."

A. Lincoln

That did not stop Emilie from again requesting a pass to sell her

cotton in November 1864:

I have been a quiet citizen and request only the right which

humanity and justice always gives to widows and orphans. I also

would remind you that your minie bullets have made us what we are."

After this insult, the Lincolns never communicated with Emilie or saw

her again.

Emilie never remarried and wore mourning clothes for the rest of her

life. After the war, she and her children moved first to Elizabethtown, Kentucky, then to Madison,

Indiana and finally, in 1912 to a house in Lexington, Kentucky,

purchased by her son, where she gave piano lessons. She was active in

the local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and took

part in many military reunions. She was named, "Mother of the Orphan

Brigade," by the Regiment’s former soldiers.

children moved first to Elizabethtown, Kentucky, then to Madison,

Indiana and finally, in 1912 to a house in Lexington, Kentucky,

purchased by her son, where she gave piano lessons. She was active in

the local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and took

part in many military reunions. She was named, "Mother of the Orphan

Brigade," by the Regiment’s former soldiers.

She became close to her nephew, Robert Todd Lincoln, who, in 1881,

helped her obtain appointment as Postmistress of Elizabethtown,

Kentucky. She served in that position until 1895. As a kindness to her

nephew, she and her daughters, Katherine and Elodie, unveiled a statute

of President Lincoln in the town square of Hodgenville, Kentucky,

Abraham Lincoln’s birthplace. Emilie died February 20, 1930, at the age

of 93, and was buried in the Todd plot in Lexington.

On September 17, 1884, Helm’s remains were exhumed from his

battleground grave in Georgia, escorted by soldiers from both the Orphan

Brigade and the First Kentucky Cavalry and reburied in the family

cemetery in Elizabethtown, Kentucky, alongside his father’s grave. His

grave stone is pictured at above, with "VICTORY," marking his final

words.

Last changed: 10/03/13

Home

About News

Newsletters

Calendar

Memories

Links Join

|