Volume

28, No. 1 – January 2015

Volume 28, No. 1

Editor: Stephen L. Seftenberg

Website:

www.CivilWarRoundTablePalmBeach.org

The President’s Message

Dues are due. Elections will be held in

January. If you wish to run for any office or serve on the Board or any

committee, please call me (561 967-8911) or e-mail me

(honeybell7@aol.com).

Gerridine LaRovere, President

January 14, 2015 Program

Steven Stanley, Map Designer for the Civil War Trust,

lives in Gettysburg and is a graphic artist specializing in historical

map design and battlefield photography. His maps, considered among

the best in historical cartography, have been a longtime staple of the

Trust and have helped raised millions of dollars for the Trust through

their preservation appeals and interpretation projects. He is

co-author with J. D. Peatruzzi of three books: The Complete Gettysburg

Guide, The New Gettysburg Campaign Handbook, and The Gettysburg Campaign

in Numbers and Losses. Stanley and Petruzzi are working on a

similar trilogy for Antietam. Stanley, James Kessler, and Wayne

Motts are also working on Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg: A Guide to

the Most Famous Attack in American History. Stanley will talk

about the history of Civil War mapping and then go into how he creates

Civil War maps for books, the Hallowed Ground magazine and the

Trust.

December 10, 2014 Program:

Robert Macomber, The Global Civil War

Mr. Macomber, here for his 12th Holiday visit, started by stating

that there have been innumerable civil wars in history, but few have

been "international" wars. He cited the English Civil War in the 16th

century, the French Civil War in the 17th century, the Spanish Civil

Wars in the early 19th century, and the American Civil War in the 19th

century. The legacy of our Civil War exists around the world today.

In the American Revolution, the American rebels wanted to bring the

war to the British, but were obviously unable to match British naval

power head on. So we resorted to "guerre de course" or commerce

raiding, a kind of guerrilla war of attrition at sea aimed at British

commerce. Few countries depended upon international commerce to the

extent the British did. John Paul Jones is the "face" of this war, but

the American rebels sent raiders all over the globe. The same strategy

was employed in the War of 1812. In both these wars, the raiders’ top

target was: oil! Whale oil provided lubrication and illumination. To

illustrate how persistent a policy, once adopted, can be, until 1890,

the U. S. Navy, faced with the fact of British primacy at sea, followed

guerre de course as official policy and built ocean raiders!

When the war started in 1861, the U. S. Navy had 65 ships in

commission – one-third were out of service being repaired, one-third

were in transit and one-third were actually in service. Only 12 ships

were on active duty in home waters and 5 were in two overseas squadrons. Suddenly, the North was faced with the reverse of the situation America

faced in the two wars with Britain. The effectiveness of the

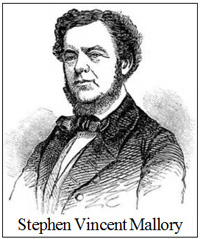

Confederacy’s policy of guerre de course is all due to two men: Stephen Mallory (1812-1873), the Confederate Secretary of the Navy and

Judah P. Benjamin (1811- 1884). the Confederate Secretary of State. Born

in Trinidad, Mallory’s father moved to Key West, Florida, but then died,

leaving his widow to raise two boys. Mallory became well-known as an

admiralty lawyer. Elected to the U. S. Senate in 1851 when the

"establishment" Democrats had a falling out with David Yulee, Mallory

worked his way up the Senate ladder. As Chair of the U. S. Senate Naval

Affairs Committee, in 1853, his committee added 6 new screw frigates to

the fleet – considered the best frigates in the world. In 1857, his

committee added 12 new sloops-of-war. which entered the navy beginning

in 1858. Without these vessels, the plight of the U. S. Navy in 1861

would have been even more parlous. When the war started in 1861, the U. S. Navy had 65 ships in

commission – one-third were out of service being repaired, one-third

were in transit and one-third were actually in service. Only 12 ships

were on active duty in home waters and 5 were in two overseas squadrons. Suddenly, the North was faced with the reverse of the situation America

faced in the two wars with Britain. The effectiveness of the

Confederacy’s policy of guerre de course is all due to two men: Stephen Mallory (1812-1873), the Confederate Secretary of the Navy and

Judah P. Benjamin (1811- 1884). the Confederate Secretary of State. Born

in Trinidad, Mallory’s father moved to Key West, Florida, but then died,

leaving his widow to raise two boys. Mallory became well-known as an

admiralty lawyer. Elected to the U. S. Senate in 1851 when the

"establishment" Democrats had a falling out with David Yulee, Mallory

worked his way up the Senate ladder. As Chair of the U. S. Senate Naval

Affairs Committee, in 1853, his committee added 6 new screw frigates to

the fleet – considered the best frigates in the world. In 1857, his

committee added 12 new sloops-of-war. which entered the navy beginning

in 1858. Without these vessels, the plight of the U. S. Navy in 1861

would have been even more parlous.

When Florida seceded, Mallory joined the fledgling Confederacy. President Jefferson Davis appointed him Secretary of the Navy in March

1861. Mallory knew the South would never be able to go "ship-to-ship"

against the U.S. Navy, so he adopted a naval strategy (supplementing the

strategy used against England in the American Revolution and the War of

1812) based on the following strategies:

(1) Deploying sea-going commerce raiders to disrupt Union

merchant shipping and divert Union warships from the blockade to

chase the raiders.

(2) Running the Union blockade using a combination of private

shipping and specially-constructed blockade-running ships operated

by the Confederate Navy.

(3) Fighting on the rivers to keep the Confederacy from being

split in two and severing its supply lines from West of the

Mississippi.

(4) Adopting and deploying emerging naval technologies

(ironclads, submersibles, and torpedoes) to attempt to keep southern

harbors, especially Norfolk, Wilmington, Charleston, Mobile ,and New

Orleans, open and maintain the flow of supplies through the

blockade.

Macomber’s talk focused on the first two of these strategies.

Initially, the Confederates tried commerce raiding by issuing "Letters

of Marque" to allow private parties to act as raiders on behalf of the

Confederate government. Due to international treaty and an inadequate

response from private ship owners, the Confederate Navy soon took over

purchasing sea-going ships to prey on Union commerce shipping and whale

hunting. These would be regular, commissioned war ships. While some of

these had great success (notably the CSS Alabama., CSS Florida,

and CSS Shenandoah), they failed to even partially disable

Union maritime commerce, although they did contribute to the eventual

demise of the U.S. merchant marine industry because of the inflation in

insurance costs. They were only partially successful at diverting Union

Navy ships off the blockade to try to hunt them down and capture them.

Blockade running was also initially entrusted to private parties, but

the private runners ultimately failed to deliver the war material needed

by the Confederacy to prosecute the war. The demand for luxury goods

(and the willingness of the Confederate aristocracy to pay whatever

price was demanded) made it more lucrative for private runners to carry

cargo to meet this demand, despite government requirements that they

carry a certain percentage of military cargo. Eventually, the

Confederate Navy chose to construct and crew its own blockade runners in

order to supply arms and equipment to the armies of the Confederacy.

Mallory embraced the use of ironclad ships as a means of going up

against the overwhelming firepower of the big frigates and sloops of the

Union Navy. The use of submersible vessels (the "Davids" and CSS

Hunley) did not achieve widespread success, and the use of

torpedoes, while effective in the latter stages of the war (in terms of

both real results and their psychological impact), failed to stem the

Northern tide.

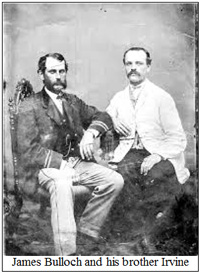

In pursuit of building a navy from scratch, Mallory sent a very

talented man, James Bulloch (1825-1901), to England and to use

Confederate cotton to purchase ocean raiders and blockade runners. Bulloch had served in the United States Navy for 15 years before

resigning his commission to join a private shipping company in 1854. When the war started, Bulloch wanted to be an ocean raider himself. After all, ocean raiders had "fun" blowing stuff up, burning things down,

and making money off prizes without killing many people in the process. Instead, he became a Confederate secret agent and their "most dangerous

man" in Europe according to the Northern State Department officials. In pursuit of building a navy from scratch, Mallory sent a very

talented man, James Bulloch (1825-1901), to England and to use

Confederate cotton to purchase ocean raiders and blockade runners. Bulloch had served in the United States Navy for 15 years before

resigning his commission to join a private shipping company in 1854. When the war started, Bulloch wanted to be an ocean raider himself. After all, ocean raiders had "fun" blowing stuff up, burning things down,

and making money off prizes without killing many people in the process. Instead, he became a Confederate secret agent and their "most dangerous

man" in Europe according to the Northern State Department officials.

Less than two months after the attack on Fort Sumter, Bulloch

established a base of operations in Liverpool. Britain was officially

“neutral” in the conflict between North and South, but private and

public sentiment favored the Confederacy. Britain was also willing to

buy all the cotton that could be smuggled past the Union blockade, which

provided the South with its only real source of hard currency. Bulloch

arranged for the construction and secret purchase of the commerce

raiders CSS Alabama and CSS Florida as well as many of the blockade

runners that acted as the Confederacy's commercial lifeline. James’s

brother, Irvine Bulloch, would serve and fight on CSS Alabama. James

also purchased a large quantity of ordnance and naval supplies, bought a

steamship SS Fingal, renamed it CSS Atlanta, filled it with this

material, and captained it to America. Bulloch returned to England

and was involved in constructing and acquiring a number of other

warships and blockade runners for the Confederacy, including purchasing

Sea

King, which was renamed CSS Shenandoah. Bulloch instructed Captain

James Iredell Waddell (1824-1886) to sail CSS Shenandoah “into the seas

and among the islands frequented by the great American whaling fleet, a

source of abundant wealth to our enemies and a nursery for their seamen.

It is hoped that you may be able to greatly damage and disperse that

fleet.” CSS Shenandoah fired the last shots of the war on June 28, 1865

during a raid on American whalers in the Bering Sea. More about this

later in Macomber’s talk.

Gideon Welles, the Northern Secretary of the Navy, faced a terrible

job. Europe favored the South for two reasons: (1) to keep cotton

flowing to its mills and (2) to undermine America’s rise as a world

power. No wonder he and his naval officers were not enthusiastic about

General-in-Chief Winfield Scott’s “Anaconda Plan.” After all, how was the

U. S. Navy, with only 65 ships, to cover over 5,000 miles of coast line? For the first two years of the war, the Northern blockade was extremely

porous. However, the North energetically built up the U. S. Navy. By the

end of the war there were 632 U. S. Naval vessels afloat. Americans have

built huge navies virtually from scratch three times in our history:

Civil War, World War I, and World War II. Before Fort Sumter, the Navy

had been kept on short rations because Congress did not trust it – in

England, the aristocratic Navy had encroached on Parliament’s powers. The first American admiral wasn’t appointed until 1862 and even then as

an “acting” Rear Admiral. The U. S. Navy also had to develop fleet

tactics from scratch. Macomber said he religiously avoids “taking sides”

between North and South, but that he clearly prefers Mallory, who was

personable and humorous, to Welles, who was neither.

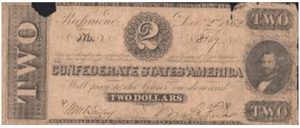

Macomber then turned to Judah P. Benjamin, one of his favorite guys and,

incidentally, one of the few living people to have their portrait on a

Confederate Two Dollar Bill! Benjamin spoke several languages, could

“schmooze” everybody. In 1861 he persuaded England and France to

recognize the Confederacy as a “legitimate belligerent,” which meant

that the South’s ocean raiders would not be treated as pirates and

“enemies of all nations.” England and, to a lesser degree France, made

lots of money off the Civil War. Britain allowed nearly all the ocean

raiders and blockade runners to be build in British shipyards in blatant

violation of its “neutrality.” The design of the ocean raiders was

“state of the art” and they were armed with Armstrong rifled cannon,

placed in both pivots, and broadsides. The South sent its “best and

brightest” officers to command these vessels. Macomber next introduced

us to two of the best and the brightest: Macomber then turned to Judah P. Benjamin, one of his favorite guys and,

incidentally, one of the few living people to have their portrait on a

Confederate Two Dollar Bill! Benjamin spoke several languages, could

“schmooze” everybody. In 1861 he persuaded England and France to

recognize the Confederacy as a “legitimate belligerent,” which meant

that the South’s ocean raiders would not be treated as pirates and

“enemies of all nations.” England and, to a lesser degree France, made

lots of money off the Civil War. Britain allowed nearly all the ocean

raiders and blockade runners to be build in British shipyards in blatant

violation of its “neutrality.” The design of the ocean raiders was

“state of the art” and they were armed with Armstrong rifled cannon,

placed in both pivots, and broadsides. The South sent its “best and

brightest” officers to command these vessels. Macomber next introduced

us to two of the best and the brightest:

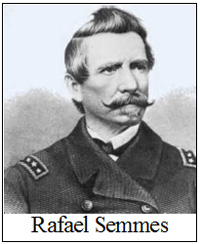

Raphael Semmes (1809-1877) was an officer in the United States Navy

from 1826 to 1860 and in the Confederate States Navy from 1860 to 1865. He was captain of the famous commerce raider CSS Alabama, Between August

1862 and June 1864, he took a record 86 prizes in the Caribbean Sea, North Atlantic, South Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans. Welles

sent many “flying squadrons” in futile effort to destroy or capture him. Welles, seriously embarrassed by this, wanted Semmes hung as a pirate. Finally, Semmes is trapped in Cherbourg, France and

CSS Alabama is sunk.

[Editor’s note: The effort begun in 1990's to salvage the wreck is a

complicated tale of international cooperation beyond the scope of this

report.] Semmes escaped and returned to the South and was promoted to

Rear Admiral. He also served briefly as a Brigadier General in the

Confederate Army. Admiral/General Semmes is the only North American to

have the distinction of holding both ranks simultaneously. Raphael Semmes (1809-1877) was an officer in the United States Navy

from 1826 to 1860 and in the Confederate States Navy from 1860 to 1865. He was captain of the famous commerce raider CSS Alabama, Between August

1862 and June 1864, he took a record 86 prizes in the Caribbean Sea, North Atlantic, South Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans. Welles

sent many “flying squadrons” in futile effort to destroy or capture him. Welles, seriously embarrassed by this, wanted Semmes hung as a pirate. Finally, Semmes is trapped in Cherbourg, France and

CSS Alabama is sunk.

[Editor’s note: The effort begun in 1990's to salvage the wreck is a

complicated tale of international cooperation beyond the scope of this

report.] Semmes escaped and returned to the South and was promoted to

Rear Admiral. He also served briefly as a Brigadier General in the

Confederate Army. Admiral/General Semmes is the only North American to

have the distinction of holding both ranks simultaneously.

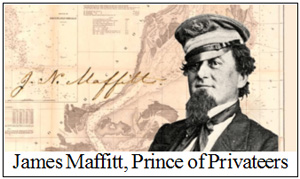

James Newland Maffitt (1819-1886), in command of

CSS Florida, set out

in January 16, 1863 and spent 6 months off North and South America and

in the West Indies, with calls at neutral ports, all the while making

captures and eluding the Northern squadrons pursuing him. It was during

this period that he acquired the nickname "Prince of Privateers" (which

was somewhat inaccurate, since he was a naval officer and not an actual

privateer.) After yielding command of CSS Florida due to ill health, at

the end of the war he commanded CSS Owl, a successful blockade runner. Instead of surrendering his ship, he took it to England. After the war

he commanded an English merchant steamer and a warship on the rebels’

side in the Cuban Ten Years War. James Newland Maffitt (1819-1886), in command of

CSS Florida, set out

in January 16, 1863 and spent 6 months off North and South America and

in the West Indies, with calls at neutral ports, all the while making

captures and eluding the Northern squadrons pursuing him. It was during

this period that he acquired the nickname "Prince of Privateers" (which

was somewhat inaccurate, since he was a naval officer and not an actual

privateer.) After yielding command of CSS Florida due to ill health, at

the end of the war he commanded CSS Owl, a successful blockade runner. Instead of surrendering his ship, he took it to England. After the war

he commanded an English merchant steamer and a warship on the rebels’

side in the Cuban Ten Years War.

Macomber then introduced us to Charles William Read (1840-1890),

class of 1860, U.S. Naval Academy. Read exhibited bravado and leadership

from the beginning of the war. He participated in the attack on the

Union blockading squadron at Head of the Passes on the Mississippi

River. When the commander of CSS McRae was wounded, Read took command of

the ship. Read then served as executive officer of CSS Arkansas during

its fight with over 30 Northern ships blockading the Mississippi River

near Vicksburg, Mississippi and served as its acting commander in her

final battle assaulting Baton Rouge, Louisiana. After the sinking of

Arkansas, Read was assigned to the CSS Florida. When Maffitt captured the

USS Clarence in Brazilian waters, Read persuaded him not to sell it but

to put him in command so he could raid the East Coast from Norfolk,

Virginia to Portland, Maine. Imagine a 23-year old ensign commanding 16

sailors and armed with one 6-pound boat howitzer and 2 “Quaker” fake

guns, planning to sail into the biggest naval base in the US and raise

havoc. Sailing North from Brazilian waters, Maffitt targets New York

City. Outside the harbor, he destroys two merchant ships. Meanwhile, by

sheer coincidence, Read in CSS Clarence is sailing along the north coast

of Long Island.

Their efforts were not planned but were brilliantly successful,

causing pandemonium among shipping circles with consequences with us

today. Besieged by complaints from insurance companies, shipping line

owners, the fishing industry, and chambers of commerce, Welles has the US

Navy desperately searching for CSS Florida but cannot find her because

Maffitt had sailed her to Bermuda to refit and refuel. Insurance rates

are skyrocketing and the merchant fleet is staying in port. According to

the New York Chamber of Commerce, by mid-1863, 150 vessels and 150 tons

worth $12 million have been captured by Confederate raiders world wide. Rather than remaining idle, merchants ships are being registered under

foreign flags or sold to British owners. Before the Civil War, the

American merchant marine had been the largest in the world. That ended

permanently in 1863!

During this raid, Lieutenant Read captured or destroyed 22 U.S.

vessels. The Northern Navy thought the raid involved a whole fleet

of Confederate ships, because, if a captured vessel was bigger or faster

or better armed, Read transferred his crew and supplies, first to CSS Tacony and finally to

CSS Archer, and would then sink his old vessel. Moreover, Read’s raid came at a fortuitous time – in New York, the draft

riots were on and blacks were being lynched; Gen. Robert E. Lee had

invaded the North and the Northern generals had lost track of him –

perhaps his target was Washington, D. C. or even New York! All of this

was sheer coincidence, but the Northern mercantile interests smelled a

real threat.

Read and his crew were captured off Portland, Maine, while attempting

to take USRC Caleb Cushing, not by the U.S. Navy, but by the local

militia. Those troops commandeered the unarmed Forest City, manhandled a gun aboard,

and took off after Read. Read, who cannot fire back for lack of powder, finally surrenders. The militia saved Read and his men from a mob who

wanted to lynch them as pirates. Read was held at Fort Warren,

Massachusetts, until he was exchanged on October 18, 1864, for a U. S.

Naval officer.

Read’s contribution to history exceeds any possible expectation. Northern maritime commerce was completely disrupted even after he was

captured because the North believed other Confederate raiders were still

at large. Insurance rates continued to escalate. The U. S. merchant

marine lost only 22 ships but shrank by 40% and has never recovered.

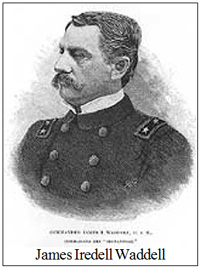

Macomber’s final vignette was of James Iredell Waddell (1824-1886),

who commanded CSS Shenandoah. Waddell, not knowing the South had

surrendered and the war was over, continued to harass the Northern

whaling fleet until September 1865, when he sailed toward Fort Alcatraz

to refit and refuel. On the way he stopped a British whaler who showed

him a newspaper saying the war is over. If he and his crew did not

surrender immediately they would truly be deemed to be pirates. Waddell

huddled with his men and all decided not to surrender in California but

to sail 9,000 miles back to Liverpool. They could not stop at any ports

on the way and subsisted on fish and rainwater, arriving in Liverpool on

November 7, 1865. Waddell refused to take a harbor pilot on board and

instead dropped anchor next to a British frigate. He “decommissioned”

his ship and then surrendered to the Lord Mayor of Liverpool. A big

legal too-do followed, with the American Ambassador demanding they be

arrested and tried as pirates. Instead a British court held that as

“legitimate belligerents” they could not be arrested. Shenandoah was

eventually sold to a British firm. Macomber’s final vignette was of James Iredell Waddell (1824-1886),

who commanded CSS Shenandoah. Waddell, not knowing the South had

surrendered and the war was over, continued to harass the Northern

whaling fleet until September 1865, when he sailed toward Fort Alcatraz

to refit and refuel. On the way he stopped a British whaler who showed

him a newspaper saying the war is over. If he and his crew did not

surrender immediately they would truly be deemed to be pirates. Waddell

huddled with his men and all decided not to surrender in California but

to sail 9,000 miles back to Liverpool. They could not stop at any ports

on the way and subsisted on fish and rainwater, arriving in Liverpool on

November 7, 1865. Waddell refused to take a harbor pilot on board and

instead dropped anchor next to a British frigate. He “decommissioned”

his ship and then surrendered to the Lord Mayor of Liverpool. A big

legal too-do followed, with the American Ambassador demanding they be

arrested and tried as pirates. Instead a British court held that as

“legitimate belligerents” they could not be arrested. Shenandoah was

eventually sold to a British firm.

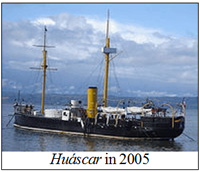

Macomber pointed out that Confederate crews were an international lot

– Brits, French, Australians, Brazilians, and sometimes even Union

sailors serving on ships captured by the ocean raiders. Today,

Confederate graves are tended in Brazil and Australia by the United

Daughters of the Confederacy. Only one Civil War era vessel still

exists, Huáscar, restored and maintained as a memorial to the Peruvian

and Chilean Navies in Talcahuano Naval Base, Chile. Macomber pointed out that Confederate crews were an international lot

– Brits, French, Australians, Brazilians, and sometimes even Union

sailors serving on ships captured by the ocean raiders. Today,

Confederate graves are tended in Brazil and Australia by the United

Daughters of the Confederacy. Only one Civil War era vessel still

exists, Huáscar, restored and maintained as a memorial to the Peruvian

and Chilean Navies in Talcahuano Naval Base, Chile.

James Bulloch, the Confederate purchasing agent in Britain, had

another interesting effect on American history. His sister, Martha

“Mittie” Bulloch, a real Southern belle, married Theodore Roosevelt,

Sr., father of Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., who disliked being called

“Teddy.” Scarlet O’Hara of Gone With the Wind fame is reputed to have

been modeled on Mittie. After TR’s father died, TR spent lots of time

with his uncle, James Bulloch, who taught him about naval strategy,

especially in the War of 1812. This inspired TR to write The Naval War

of 1812 , published when he was only 24. TR also studied Captain Mahan’s

The Influence of Sea Power on History. It is no accident that TR, as

Assistant Secretary of the Navy, implemented updated strategy and fleet

tactics and fostered a modern navy that replaced the British Navy as the

world’s dominant sea power. Nor is it an accident that TR’s cousin,

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, also served in the same post. James Bulloch, the Confederate purchasing agent in Britain, had

another interesting effect on American history. His sister, Martha

“Mittie” Bulloch, a real Southern belle, married Theodore Roosevelt,

Sr., father of Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., who disliked being called

“Teddy.” Scarlet O’Hara of Gone With the Wind fame is reputed to have

been modeled on Mittie. After TR’s father died, TR spent lots of time

with his uncle, James Bulloch, who taught him about naval strategy,

especially in the War of 1812. This inspired TR to write The Naval War

of 1812 , published when he was only 24. TR also studied Captain Mahan’s

The Influence of Sea Power on History. It is no accident that TR, as

Assistant Secretary of the Navy, implemented updated strategy and fleet

tactics and fostered a modern navy that replaced the British Navy as the

world’s dominant sea power. Nor is it an accident that TR’s cousin,

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, also served in the same post.

Macomber closed his fascinating talk with an exploration of the

problems facing the Confederate ocean raids once they captured a

merchant or whaling ship. For example, when CSS Alabama, took a

prize off the coast of Vietnam, there was no port and no admiralty court

to award prize money, Semmes burned the prize ship. An

alternative would be to put the captured seamen on board the prize,

"parole" the ship, have its captain sign a "bond" on behalf of the

owners and order him to sail to a port that had a court where the ship’s

owners were supposed to pay off the bond to the Confederates States of America.

Macomber doubted that many of these bonds were actually paid off.

The audience gave Robert Macomber a well-earned round of applause for

an entertaining talk.

Last changed: 01/08/15

Home

About News

Newsletters

Calendar

Memories

Links Join

|