Volume

28, No. 8 – August 2015

Volume 28, No. 8

Editor: Stephen L. Seftenberg

Website:

www.CivilWarRoundTablePalmBeach.org

President’s Message

At the July meeting several people asked me why we were not discussing

current events. The purpose of the Round Table is the study and

discussion of the Civil War, the years prior and immediately thereafter.

It is not appropriate for the Round Table to offer an opinion on any

recent political issues.

Due to space limitations,

the printed version of the newsletter could not contain this paragraph. Two items: one good, one

bad. First the good: Our

favorite holiday speaker, Robert Macomber, will speak to us on

Wednesday, December 9 at 7 PM.

He will also give a talk at the Four Arts on Tuesday, December 8,

2015 (the day before our meeting), beginning at 5:30 PM. At both

meetings, he will assuredly discuss his newest book, “Assassin’s Honor.”

Then the bad news: I got a letter from Mary Barnt, editor of the Peace

River Civil War Roundtable that her roundtable has ceased to exist. We

are fortunate in maintaining interest, with an inviting speakers,

website and newsletter, with over 40 attendees at the July meeting.

But we always need new blood to grow let alone survive. Bring a

friend to the next meeting!

Gerridine LaRovere, President

August 12, 2015

Meeting

Lavinia (“Ellie”) Ream (9/23/1847 -

11/20/1914)

Our President says, “I read a brief article about

Vinnie Ream in a Civil War magazine and found her fascinating. She is

not a well-known name; but the more research I did, the more captivating

she became. Vinnie was petite, astute, well-connected, confident, and

artistically talented. Her friends and acquaintances were a compendium

of many Civil War personalities. Benjamin Butler, “the Beast of New

Orleans,” despised her, but General William Tecumseh Sherman was

enamored of her. While married, Sherman corresponded with her for four

years. Were the letters intimate or just flowery Victorian prose? At the

age of 18 she was the first women to receive a federal commission to

make a life-size statue of the slain President Lincoln. Was Vinnie

responsible for influencing the single vote by which President Andrew

Johnson escaped conviction in the Senate? Was she a talented, dedicated

artist with good political connections or just a wily self-promoter? See

you in August, and you be the judge.

July 8, 2015 Meeting

“The Smallest Tadpole in the Dirty Pool of Secession” – Florida in the

Civil War

Eliot Kleinberg, born in

South Florida, has spent nearly four decades as a reporter, including

more than a quarter-century at The Palm Beach Post in West Palm Beach.

He has written 10 books, all focusing on Florida, including "Black

Cloud," on the great 1928 Okeechobee Hurricane; two "Weird Florida"

books; and "Palm Beach Past" and "Wicked Palm Beach," both collections

of items from his weekly local history column in the Post. His tenth,

“Peace River,” is a historical novel based at the end of the Civil War.

The son of longtime prominent South Florida journalist Howard Kleinberg,

he is a University of Florida graduate,

a member of the Florida, South Florida and Palm Beach County

Historical Societies. He and his wife are the parents of two adult sons

and live in suburban Boca Raton. Eliot Kleinberg, born in

South Florida, has spent nearly four decades as a reporter, including

more than a quarter-century at The Palm Beach Post in West Palm Beach.

He has written 10 books, all focusing on Florida, including "Black

Cloud," on the great 1928 Okeechobee Hurricane; two "Weird Florida"

books; and "Palm Beach Past" and "Wicked Palm Beach," both collections

of items from his weekly local history column in the Post. His tenth,

“Peace River,” is a historical novel based at the end of the Civil War.

The son of longtime prominent South Florida journalist Howard Kleinberg,

he is a University of Florida graduate,

a member of the Florida, South Florida and Palm Beach County

Historical Societies. He and his wife are the parents of two adult sons

and live in suburban Boca Raton.

Eliot started out by

stating that the “average” resident of Palm Beach County knows nothing

about the history of Florida in the Civil War and that he sees one of

his missions in life being to bring the fascinating story to the public

(currently, with his January 8, 2015 column in the Neighborhood Post

section down to his June 11, 2015 column).

Eliot then debunked the factoid that Florida was so named because

the sailors saw flowers on the beach. In reality, the discovery came

during the Festival of Flowers in Spain.

What were the real

motives for secession? For

the “average” Floridian, it may have been to protect my land from Damn

Yankee invaders, but for the ruling class, it was clearly to protect

slavery. The “Declarations

of Secession” adopted by the various states usually were silent on the

reasons, but the underlying cause was clearly spelled out in the

“Declaration of Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession

of South Carolina from the Federal Union,” dated December 24, 1860:

The specific issues stated were the refusal of some states to

enforce the Fugitive Slave Act and clauses in the U.S. Constitution

protecting slavery and the federal government's perceived role in

attempting to abolish slavery. “...while these problems had existed for

twenty-five years, the situation had recently become unacceptable due to

the election of a President who was planning to outlaw slavery... [and

the] ... increasing hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding States

to the Institution of Slavery.”

Not all slave holders

favored secession. On January 7, 1861, the secession convention voted

that Florida should legally resign from the United States. When the

secession ordinance was read on the east portico of the capitol building

before a cheering crowd, former territorial governor Richard Keith Call

(10/24/1792 - 9/14/1862), one of the founding fathers of Florida statehood

and one of the state’s largest slave-holders, angrily cried that the

delegates had “opened the gates of Hell, from which shall flow the

curses of the damned which shall sink you to perdition!”

The Civil War almost

started at Fort Pickens, on Santa Rosa Island. On January 10, 1861, the

same day Capt. Anderson consolidated his forces in Fort Sumter, South

Carolina, Lt. Adam J. Slemmer consolidated the men in the 5 forts

bordering Pensacola Bay in Fort Pickens and refused to surrender it. The

Confederates, under Braxton Bragg, planned to attack on April 12, 1861,

but balked when they learned that Fort Sumter had been bombarded and

captured, triggering war and allowing Fort Pickens to be resupplied and

reinforced and remain in Union hands. The Civil War almost

started at Fort Pickens, on Santa Rosa Island. On January 10, 1861, the

same day Capt. Anderson consolidated his forces in Fort Sumter, South

Carolina, Lt. Adam J. Slemmer consolidated the men in the 5 forts

bordering Pensacola Bay in Fort Pickens and refused to surrender it. The

Confederates, under Braxton Bragg, planned to attack on April 12, 1861,

but balked when they learned that Fort Sumter had been bombarded and

captured, triggering war and allowing Fort Pickens to be resupplied and

reinforced and remain in Union hands.

Despite secession fever,

there were many pockets of Union loyalists. The sparse population meant

that the biggest battles took place in Virginia and along the

Mississippi River and most of the eligible white men in Florida went

North or West to fight. Of the 70,679 white citizens listed in the 1860

census, Florida sent over 15,000 men and boys to fight for the

Confederacy, of whom over 5,000 died (both statistically the heaviest

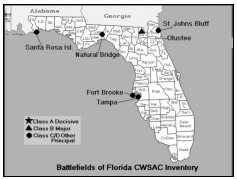

contribution by any state). However, there were celebrated battles North

of Palm Beach – Santa Rosa Island (10/9/1861), Tampa (6/30-7/1/1862),

St. John’s Bluff (10/1-10/3/1862, Fort Brooke (10/16-18/1863) and the

two most celebrated battles, Olustee (2/20/1864), and finally Natural

Bridge (03/06/65). More about the last two battles later.

One incident in our area

was the not-so-bloody Battle of the Jupiter Lighthouse. Confederate blockade-runners familiar with the waters didn't need the light

(which used a Fresnel lens) and didn't want it revealing them to

Union patrols. Assistant keeper August Oswald Lang, a German immigrant

and a proud citizen of the Confederate States of America, ordered his

boss to surrender the lighting mechanism. Keeper J. F. Papy, loyal to

his federal paycheck, said no, but was convinced otherwise. The rebels

hid the key components of the beacon, and it was recovered after the war

and is still in place in the lighthouse.

blockade-runners familiar with the waters didn't need the light

(which used a Fresnel lens) and didn't want it revealing them to

Union patrols. Assistant keeper August Oswald Lang, a German immigrant

and a proud citizen of the Confederate States of America, ordered his

boss to surrender the lighting mechanism. Keeper J. F. Papy, loyal to

his federal paycheck, said no, but was convinced otherwise. The rebels

hid the key components of the beacon, and it was recovered after the war

and is still in place in the lighthouse.

Eliot pointed out that

with the capture of Vicksburg, on the Mississippi River, Century Village

would not exist! Why? When

it surrendered, the railroad to Texas, which had been the “Rebel

Warehouse,” the source of beef, pork, salt, turpentine and soldiers, was

cut and the Confederates turned to Florida as a replacement.

President Lincoln, facing

a tough reelection campaign in 1864, saw Florida as the weakest of the

Southern states. He asked

his generals to work up a plan to capture Tallahassee.

The result? The Battle of Olustee (2/20/1864), viewed by the

South as a “rout,” was the second bloodiest battle in the war, measured

by the percentage of killed and wounded to total engaged. (Note:

In the aftermath there is substantial evidence that Confederate militia

men killed Union black soldiers who were wounded or attempting to

surrender.)

It is also the scene of large annual Reenactments (February 13-14,

2016). The last major battle in Florida was the Battle of Natural Bridge

(March 6, 1865). Union

forces, attacking from the West, were met by a hastily-gathered force

consisting of Seminole War veterans (the “Gadsden Grays”) and military

cadets from the Florida Military and Collegiate Institute that would

later become Florida State University, hated rivals of Eliot’s alma

mater, University of Florida. The result was another smashing

Confederate victory that meant that Tallahassee was the only Southern

capital never to fall to a Northern army during the war.

By the end of the

fighting, Florida was flat on its back.

One final casualty was its governor, John Milton, who committed

suicide rather than surrender.

For some time there would be no effective government in the parts

of the state that had been controlled by the Confederacy. The war would

end in ignominy and flight – Some, Judah P. Benjamin (who had been

Confederate Attorney General, Secretary of War and Secretary of State,

and John C. Breckinridge (who had been Vice President of the United

States under Buchanan, a U. S. Senator for 9 months, a Brigadier General in the Confederate Army and finally for one month, Confederate Secretary

of War) both escaped to England. President Jefferson Davis almost made

it to Florida, being captured near Irwinville, Georgia.

Dr. Samuel Mudd 12/20/1833-1/10/1883), who treated John Wilkes

Booth after Booth broke his leg jumping from Lincoln’s box seat, was

sentenced to life imprisonment in Fort Jefferson, in the Dry Tortugas 70

miles West of Key West. When

Mudd tried to escape he was shifted from the hospital to the carpentry

shop, where he wore leg irons while working there.

In 1867, Mudd saved many lives in a Yellow Fever epidemic.

President Andrew Johnson pardoned Mudd on February 18, 1869, but

efforts to expunge his conviction continue to this day.

Two Presidents, Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, have expressed

their belief that Mudd was innocent of any crime. Fort Jefferson is now

a tourist attraction, but has a blank military history. By the time it

was finished, its 420 cannons were obsolete and could not reach enemy

ships whose own cannons had the fort in their range.

in the Confederate Army and finally for one month, Confederate Secretary

of War) both escaped to England. President Jefferson Davis almost made

it to Florida, being captured near Irwinville, Georgia.

Dr. Samuel Mudd 12/20/1833-1/10/1883), who treated John Wilkes

Booth after Booth broke his leg jumping from Lincoln’s box seat, was

sentenced to life imprisonment in Fort Jefferson, in the Dry Tortugas 70

miles West of Key West. When

Mudd tried to escape he was shifted from the hospital to the carpentry

shop, where he wore leg irons while working there.

In 1867, Mudd saved many lives in a Yellow Fever epidemic.

President Andrew Johnson pardoned Mudd on February 18, 1869, but

efforts to expunge his conviction continue to this day.

Two Presidents, Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, have expressed

their belief that Mudd was innocent of any crime. Fort Jefferson is now

a tourist attraction, but has a blank military history. By the time it

was finished, its 420 cannons were obsolete and could not reach enemy

ships whose own cannons had the fort in their range.

The Civil War was a

calamity for Florida, as it was for the Confederate states.

However, a bright spot was that many Northern soldiers posted

there during Reconstruction were attracted to snow-free living.

Florida passed a law encouraging the building of railroads from

the North to foster tourism. Henry Flagler, induced by the grant of

2,000 acres of land, laid 300 miles of track to the “American Riviera,”

leading to the first “Boom.” Eliot sees Florida’s history as a moving

“jump rope” – booms (1880s, 1920, post-World War II) followed by bust.

The population tells the story: 1940 (2 million), 1950 (3

million), 1970 (7 million) and 2015 (20 million).

In conclusion, Eliot

reiterated his conclusion that the Civil War was a catastrophic

disaster. To continue to argue over its “cause” is a useless waste.

We should honor the dead and the maimed on both sides, including

the many wives, widows and children on the home front who also suffered

greatly. The greatest

“thing” to remember about the Civil War is the fact that we fought it.

It should not be romanticized and should not include revisionist history

for political purposes. For whatever reasons it was fought, the South

“lost” the war, and should have “gotten over it” by now.

After his rousing talk,

Eliot Kleinberg answered questions and received equally rousing

applause.

[Editor’s comment: The

day of Eliot’s talk, author Peter Manseau wrote an article in The New

York Times entitled, “The Many Images of Jefferson Davis,” in which he

says, “Among Southerners, the abuse [Davis] endured – at the hands of

both wags like Barnum and his jailers at Virginia’s Fort Monroe – took

on a life of its own. His suffering became the passion play of the Lost

Cause, the nearly religious cult of grievance that convinced subsequent

generations of the Union’s intent not only to defeat the Confederacy but

to emasculate it. . . . Recent debates over relics of the Confederacy –

in South Carolina, the United States Capitol, and elsewhere – only

underscore how successful 150 years of revisionism can be.”

Last changed: 07/28/15

Home

About News

Newsletters

Calendar

Memories

Links Join

|