Volume

28, No. 9 – September 2015 Volume

28, No. 9 – September 2015

Volume 28, No. 9

Editor: Stephen L. Seftenberg

Website:

www.CivilWarRoundTablePalmBeach.org

President’s Message

The Palm Beach County Round Table was founded on September 16, 1987.

Charter members were Robert Godwin, Rodney Dillon, Greg Parkinson, and

Dr. Joel Gordon. Thank you to everyone who has helped us get to this

anniversary. Without your assistance, no matter how large or small, the

Round Table would not be the viable and successful organization that it

is today. I would like to give special recognition to the Board for

their time and hard work.

Gerridine LaRovere, President

September 9, 2015 Meeting

Craig Freis brings actual Civil War Era newspapers and magazines.

Inquiring minds want to know the latest news on the war front, politics

and social events during the war years. You will have that opportunity

at the September meeting. Craig Freis has acquired actual copies of the

New York Times, New York Herald, Harpers, Frank Lesley Illustrated and

regional newspapers. Everyone will be given a topic and will search for

an article relating to it in the newspapers and magazines Craig has

brought to the meeting. Bring a magnifying glass. Sometimes the print is

small.

August 12, 2015 Meeting

Vinnie Ream, Girl Sculptress

Gerridine LaRovere brought little-known sculptress, Vinnie Ream, to

life:

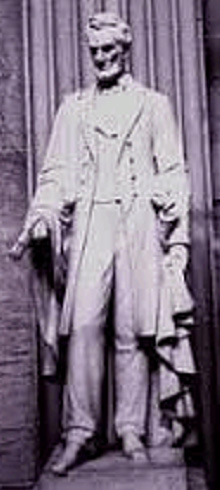

January 25, 1871–Despite the January freeze, a spectacular dedication

ceremony was about to take place in the Capitol Rotunda. Bundled in warm

clothing, eager citizens awaited the formal procession of dignitaries

about to enter the great ball. At precisely 7:30 PM officials began to

march into the building as scheduled. First, came Senators and

Representatives, followed by the Justices of the Supreme Court, and,

then, various military officials including General William T. Sherman,

and then other government officials and the families of the invited

guest. As the great Rotunda doors were thrown open, the crowd waiting

outside rushed in and tried to find the few remaining seats that were

available. Some considered themselves fortunate to find a place where

they could stand against the wall. The crush was so great that guards

were quickly forced to close the doors. Hundreds were unable to enter.

Throughout the ensuing ceremony the crowd outside would clamor at the

doors and pounding filled the hall "like roaring cannon."

Why

was everyone in Washington, DC, the city of statues, so excited about

this particular work? This was no ordinary dedication or ordinary

statue. Congress was about to unveil its very first commissioned

life-size statue of Abraham Lincoln. Tonight some of his oldest friends

would gather to pay tribute to his memory and pass judgement on the soon

to be unveiled work. Among the guest was Associate Justice David Davis

who rode the law circuit with Lincoln and helped him to become

president. Also in the audience was Vinnie Ream, the girl sculptress who

at the age of 18 became the first woman ever contracted by the United

States government to create a sculpture. Why

was everyone in Washington, DC, the city of statues, so excited about

this particular work? This was no ordinary dedication or ordinary

statue. Congress was about to unveil its very first commissioned

life-size statue of Abraham Lincoln. Tonight some of his oldest friends

would gather to pay tribute to his memory and pass judgement on the soon

to be unveiled work. Among the guest was Associate Justice David Davis

who rode the law circuit with Lincoln and helped him to become

president. Also in the audience was Vinnie Ream, the girl sculptress who

at the age of 18 became the first woman ever contracted by the United

States government to create a sculpture.

President Ulysses S. Grant and Vice President Schuyler Colfax were

seated on the speaker's platform. The Rotunda was brightly illuminated

with flags from floor to dome. The Marine band played dirges. Numerous

speeches were given by members of Congress eulogizing Lincoln. Finally,

Judge David Davis rose and stepped over to the statue covered in a silk

flag donated by weavers in Lyons, France. He raised the covering very

slowly by pulling on a gold cord disclosing the marble base with the

simple words ABRAHAM LINCOLN. Removing the rest of the veil, he

declared, “This is but a rough casket in which God lodged one of his

brightest jewels.”

After a momentary hush spontaneous applause broke out that echoed

through the Rotunda like a “clap of thunder,” said one witness. The

life-size statue of white marble was a resounding success. lt depicted a

solemn Lincoln. The President's head is bent slightly forward with his

eyes fixed on the viewer. His right leg is slightly bent and right arm

is extended. He is looking down at his right hand, which holds the

Emancipation Proclamation and his left is clutching his flowing cloak.

Senator Matt Carpenter took Vinnie's petite hand and escorted her to the

center of the platform. After another round of applause, everyone was

waiting for the fragile, youthful sculptor with the abundance of

Dora-like curls to speak. She only bowed and immediately sat down.

Later, Vinnie said that she was “too full of tears to speak. Cheers and

flowers greeted me indicating satisfaction with my work.”

Who was Vinnie Ream? To her supporters, she was a girl from the

Wisconsin wilderness, a “prairie Cinderella.” To her detractors, she was

a shameless flirt who used her feminine wiles and had a mediocre talent

at best. Let's take a look at Ginnie's interesting life so that you can

decide.

Lavinia Ellen Reams was born September 25, 1847 in a simple log cabin in

Madison, Wisconsin, then a fledgling frontier town. Ginnie lay claim to

being the first baby to be born in Madison. Her parents were Robert Lee

Ream and Lavinia MacDonald Ream. Robert was a surveyor and Wisconsin

Territory official. The Reams also operated a stage coach stop and used

their home as a hotel. Guest slept on the floor. Ginnie had limited

formal education. However, the Winnebago Indians taught her to paint and

draw. Due to her father’s surveying job they moved several times. In

1857 the family moved to western, Missouri and she attended the academy

section of Christian College in Columbia, Missouri. During this time

Ginnie studied art, literature and music. She wrote songs and even had

them published. She was introduced to James Rollins, a local lawyer and

politician, as an outstanding student. In 1861, the family was in Fort

Smith, Arkansas. Her brother, Robert, enlisted in the Confederate Army

while the rest of the family managed to work their way through

Confederate lines to Washington, D.C. Her father could only work part

time due to his arthritis. Realizing that finances were tight, in 1862

Vinnie appealed to political friends and obtained a job with the federal

government as a clerk in the dead letter office. She was the first woman

to do so and being just short of her fifteenth birthday, she lied about

her age. To help with the War effort she wrote letters for wounded

soldiers and sang at hospitals and churches. Vinnie later wrote that she

said to her mother, “I feel that I am to have some special work in the

world. I don't know what it is, but I must be ready when it comes.” She

soon found out what it would be.

Family friend, James Rollins was elected to the U.S. House of

Representatives from Missouri. In 1863, he took Vinnie to visit the

studio of sculptor Clark Mills to request a sculpture for Christian

College in Missouri. Mills was the most prominent sculptor of that time.

He created the statue of Andrew Jackson in Lafayette Square and George

Washington in Washington Square. While watching the artist, Vinnie

suddenly said, “I can do that.” Mills gave her some clay. Of this

transforming day she later said, “I felt at once that I, too, could

model and ... in a few hours I produced a medallion [of an Indian

chief].” Mills was impressed with her finished product. With Rollins’

help, Vinnie worked part time for Mills and her talent blossomed under

his tutelage. Soon she was earning enough money to quit the postal

office.

Vinnie

was renowned for her beauty and dark eyes. She was petite--barely five

feet, slender, with an abundance of long dark curls and a very winning

personality. At the age of 17 she understood the importance of building

not only her artistic talent but also her social portfolio. She

developed many personal connections with the powers that be. Mills'

studio was the perfect location for this. His studio was in one of the

wings of the Capitol building and was a popular spot for politicians.

There is little doubt that she was ambitious, but Victorian society

frowned on women who had a career. Therefore, she cultivated a sweet and

demure manner and had considerable charm. Vinnie

was renowned for her beauty and dark eyes. She was petite--barely five

feet, slender, with an abundance of long dark curls and a very winning

personality. At the age of 17 she understood the importance of building

not only her artistic talent but also her social portfolio. She

developed many personal connections with the powers that be. Mills'

studio was the perfect location for this. His studio was in one of the

wings of the Capitol building and was a popular spot for politicians.

There is little doubt that she was ambitious, but Victorian society

frowned on women who had a career. Therefore, she cultivated a sweet and

demure manner and had considerable charm.

She often saw President Lincoln on the streets in Washington and was

determined to sculpt him. At first Vinnie tried to portray him from

memory and pictures but was not pleased with the results. On her own she

approached James Rollins to help her secure sittings with Lincoln; he,

in turn, asked Illinois Senator Orville Browning to win over the

President. At first, Lincoln said that he would not sit for her, but

upon learning that she was a young, poor, ambitious girl, he agreed.

Vinnie said Lincoln sat for her for five months one half hour a day in

his White House office. That is probably an exaggeration. Mary Lincoln

disliked Vinnie, never acknowledged the possibility that the President

sat for Vinnie and told her, “Every friend that my husband knew was

familiar to me and your name was not on the list.” It is likely that he

sat for her a few times in order to make the detailed bust that she did

sculpt. That particular bust was not completed when Vinnie wrote on

April 14, 1865 "Came the great tragedy."

The Lincoln bust was slowly completed and praised by the parade of

people visiting Mills Studio in the Capitol building. This positive

response encouraged her to seek the $10,000 commission offered by

Congress for a full-length statue of Lincoln. Few commissions for a

sculpture had been awarded by the federal government. The country's best

artists competed including Clark Mills, Harriet Hosmer and Thomas

Crawford. Others may have applied but Vinnie campaigned. One of the

first things she did was write a letter to the U.S. House Committee for

Public Buildings and Grounds. Others were sent to work on her behalf. In

April, 1866, a remarkable petition arrived at the committee's office

stating, “The undersigned ... being personally acquainted with Miss

Vinnie Ream take great pleasure in endorsing her claims upon public

patronage.” lt was signed by President Andrew Johnson, his Cabinet, 31

Senators, 101 current and past Representatives and 31 other notables

such as General George A. Custer.

Not everyone was on the Vinnie bandwagon. Mrs. Jane Grey Swisshelm, a

vitriolic reporter with a Pittsburgh newspaper, began a smear campaign.

She wrote, “Ream is a young girl ... who has been studying art for a few

months, never made a statue, has some plaster busts on exhibition,

including her own minus clothing to the waist, has a pretty face ...

sees members at their lodgings.”

On July 26, 1866, the House passed the resolution to award her the

commission by a vote of 67 to 7 but she ran into trouble in the Senate.

With Vinnie looking on the great debate began. Senator Jacob Howard

questioned her artistic talents and said she only had a "peculiar talent

known commonly as lobbying." Calling a woman a lobbyist was considered a

vile slur. In the vernacular of the time, it meant a woman whose favors

politicians traded among themselves. Senator Charles Sumner sided with

Howard, stating, “She may make a statue but she cannot make one that you

will be justified in placing in this national Capitol.” Senator James

Nesmith got the floor and pointed out,” The Senator might have raised

the same objection to Mr. Lincoln, that he was not qualified for the

Presidency because his reading had not been as extensive as that of the

Senator or because he lived among rude and uncultivated society.”

Nesmith continued and alluded to Sumner's admiration for all things

European and noted bitterly, “If this young lady and the works which she

has produced had been brought to his notice by some near-sighted,

frog-eating Frenchman, with a pair of green spectacles on his nose, the

Senator would ... vote her $50,000.”

Sumner seriously underestimated Vinnie. On July 27, 1866, the Senate

voted 23 to 9 in her favor. Vinnie received a contract with Interior

Secretary Harlan for $10,000 (half payable on completion of the plaster

cast and the other half upon completion of the marble statue). Critics

asserted that her success had more to do with her charm and political

connections than her artistic ability. However, you need to be the judge

of that.

Since she had no studio of her own, Vinnie was assigned Room A in the

Capitol's basement. She worked with a live dove on her shoulder and

dressed like a "mature Botticelli cherub." Her studio became a popular

meeting place for congressmen, senators, cabinet officials, diplomats,

and journalists. Watching her work, a New York reporter noted her

beauty, “tiny pink fingers,” and "long raven lashes." She received

hundreds of written and verbal proposals of marriage. Vinnie asked Mrs.

Lincoln to borrow a suit that the President wore in order to get the

measurements and proportions correct. Mrs. Lincoln at first said, “No,”

but after many requests she relented and finally agreed to supply what

Vinnie needed. None of these distractions broke her concentration on the

work before her, but there were other interruptions.

As she worked on the plaster statue, Vinnie found herself in the middle

of a political firestorm. While she labored downstairs, the impeachment

crisis was brewing upstairs and almost stopped her work permanently.

This petite girl become the focus of another smear campaign. Many

Radical Republicans believed that Vinnie's studio was a pro-Johnson

strategy room and claimed that she persuaded Senator Edmond Ross,

R-Kansas, to cast his vote against impeachment. lt is somewhat murky as

to what she actually did, but the Republicans felt she had great

influence over Ross. Since Ross was a boarder at the Ream home and

Vinnie still lived there, the Radicals were certain that she was

influencing Ross’s vote. The night before the vote in the Senate, the

Republicans sent an emissary to the Ream home to determine how Ross was

going to vote. They sent Daniel Sickles because he had the reputation as

a “ladies man” and might charm the protective Vinnie into letting him

see Ross. Vinnie entertained Sickles for several hours by serving him

tea and singing. At times she whispered to someone (believed to be Ross)

behind closed doors. Sickles finally left at 4:00 AM, telling Vinnie,

“He is in your power and you choose to destroy him.” Ross cast the

decisive “not guilty” vote. He wrote his wife, “Millions of men are

cursing me today, but they will bless me tomorrow. But few knew of the

precipice upon which we all stood.” He was never reelected but years

later became the territorial governor of New Mexico.

Vinnie was stunned by the furor swirling around her. Once again she was

branded a “female lobbyist” by Republicans. The House voted to evict her

from the Capitol studio. Benjamin Butler demanded she be “cleared out”

and "if the statue ... be spoilt ... I shall be very glad of it.” Once

again Vinnie reached out to sympathetic politicians and reporters. A

Missouri newspaper leaped to her defense stating that if her studio were

to close the statue would “shrink and crack to pieces” into “a shattered

shapeless mass to be to be moistened by a young girl’s tears.” She

weathered the storm by a ringing endorsement signed by General Grant, 31

Senators, 104 Representatives, and even the floor leader of the

Impeachment, Senator Thaddeus Stevens, R-Pennsylvania. Vinnie kept her

studio along with a commission to make a bust of Senator Stevens.

The

life-size Lincoln plaster model was completed and inspected by Interior

Secretary Orville Browning, who thought that the statue “bears a

faithful resemblance to the original.” This was a great compliment to

Vinnie because Browning knew Lincoln for thirty years. The statue was

packed and shipped to Rome. As was the custom of the time, the statue

would be carved from a block of marble by skilled Italian craftsmen.

From the quarries in Carrara, Italy, she chose the purest white marble

for the statue. The

life-size Lincoln plaster model was completed and inspected by Interior

Secretary Orville Browning, who thought that the statue “bears a

faithful resemblance to the original.” This was a great compliment to

Vinnie because Browning knew Lincoln for thirty years. The statue was

packed and shipped to Rome. As was the custom of the time, the statue

would be carved from a block of marble by skilled Italian craftsmen.

From the quarries in Carrara, Italy, she chose the purest white marble

for the statue.

Vinnie studied in Paris and Rome but, once again, she did not neglect

the social and business aspects of a young American artist abroad. She

encouraged the artist community to visit her studio in Rome. From

December, 1869 to October, 1870, Vinnie's guest book had over 500

signatures. She continued working too. She created a life-size statue of

“Sappho” and did the “Spirit of the Carnival.” Many

people sat for her and she sculpted busts of Haulbach, Liszt, Cardinal

Antonelli, John Jay, and others. GPA Healy asked her to pose for him and

painted her portrait.

In late 1870, Vinnie returned to Washington for the unveiling of the

Lincoln statue and dedication in January 1871. Praise was almost

universal. Remarks in the newspapers included “boldly and powerfully

executed,” “extraordinary work for a child,” and “unfathomable

melancholy of the eyes.” To this day many critics feel that she captured

and conveyed Lincoln's burden of the war years. But within weeks the

tide began to turn. Many women reporters were highly critical of the

piece and called it “a frightful abortion” and “lifeless and soulless.”

Hiram Powers, a noted American sculptor, blasted the statue as a

“caricature” and Vinnie simply a “female lobbyist” with “no talent for

art.” Through the years the statue continued to be controversial. In

1873, Mark Twain intensely disliked the work and said that Lincoln's,

expression looked as if “he was finding fault with the washing.”

Whether pilloried or praised, Vinnie sought to be recognized as a

respected artist. This was a difficult task for a woman in the Victorian

Era. No matter how people felt about Vinnie, she became a celebrity.

Picture postcards of her and her artwork were sold in the Capitol and on

the street. Her studio and salon was at 235 Pennsylvania Avenue. By

staying in Washington, she was able to maintain her many connections and

always had visitors. During her career she sculpted Susan B. Anthony,

Henry Ward Beecher, Frederick Douglas, Horace Greeley, General George A.

Custer, General George McClellan, General Grant, General Fremont, and

Ezra Cornell. During this time Vinnie became the sole supporter of her

family.

In 1872, a Congressional resolution was introduced calling for a full

length statue of Admiral David Farragut. Vinnie was determined to get

the $20,000 commission. Artists had nine months to submit their models.

Immediately, Vinnie went to work on the model and her Washington

connections. She asked Mrs. Farragut, who became her champion, for the

names of the Admiral's friends and wrote each one asking for their

support. Twenty-four sculptors competed for the honor. By January 1873,

thirteen models were submitted. The only larger than life entries were

by Vinnie and Horatio Stone. The press reviewed the submissions of the

others with such comments as “Farragut looks like he was throwing a rope

to a trapeze performer,” and “a good deal of pedestal and precious

little Farragut.” President Grant called Vinnie's work “first rate.”

Admiral David Porter claimed that hers was “the only likeness in the

lot.”

General

Sherman, chairman of the committee considered the commission. was one of

Vinnie' s most ardent supporters. On Valentine's Day, 1873 Sherman

viewed all of the Farragut models and met Vinnie when she invited him to

her studio. Days later he wrote “the plaster model of Vinnie Ream struck

me decidedly as the best likeness and recalled the memory of the

Admiral's face and figure more perfectly than any other model.” Thus

began a four year relationship between Vinnie and Sherman. Their letters

were extremely flirtatious and often suggestive. He told Vinnie to write

him freely and often because "I destroy your letters. You must do the

same of mine for in the wrong hands suspicion would not stop short of

wrong--which we must not even think of." However, Vinnie did not dispose

of his letters. Sherman had more on his mind than the statue. He offered

to take Vinnie for a carriage ride so they could have "the back seat to

ourselves." On another occasion he took her handkerchief mistakenly but

used it as an excuse to see her. He told her how bored he was at his

office and wanted to come to her studio so she could sing to him. In

another letter Sherman wrote,"I often think of your studio and my

precious moments there and wonder if you miss me and who now has the

privilege of toying with your long tresses and comforting your imaginary

distresses." General

Sherman, chairman of the committee considered the commission. was one of

Vinnie' s most ardent supporters. On Valentine's Day, 1873 Sherman

viewed all of the Farragut models and met Vinnie when she invited him to

her studio. Days later he wrote “the plaster model of Vinnie Ream struck

me decidedly as the best likeness and recalled the memory of the

Admiral's face and figure more perfectly than any other model.” Thus

began a four year relationship between Vinnie and Sherman. Their letters

were extremely flirtatious and often suggestive. He told Vinnie to write

him freely and often because "I destroy your letters. You must do the

same of mine for in the wrong hands suspicion would not stop short of

wrong--which we must not even think of." However, Vinnie did not dispose

of his letters. Sherman had more on his mind than the statue. He offered

to take Vinnie for a carriage ride so they could have "the back seat to

ourselves." On another occasion he took her handkerchief mistakenly but

used it as an excuse to see her. He told her how bored he was at his

office and wanted to come to her studio so she could sing to him. In

another letter Sherman wrote,"I often think of your studio and my

precious moments there and wonder if you miss me and who now has the

privilege of toying with your long tresses and comforting your imaginary

distresses."

The committee for the Farragut commission did not vote until 1873.

Before the vote, Vinnie strongly urged Sherman to lobby the two senators

on the committee, Justin Morill of Vermont and Simon Cameron of

Pennsylvania. At first, he said he could not do that, but eventually he

did. Despite his efforts the committee rejected all models. The New York

Times rejoiced, "The nation ought to feel particularly gratified when it

reflects upon its narrow escape from another of Miss Ream's

eccentricities in bronze." Once again Congress took up the matter, in

February, 1874, and once again Vinnie worked behind the scenes by

getting recommendations. Congress shifted the responsibility for the

selection of the artist to Secretary of the Navy, George Robeson. He

resented all the pressure that was thrust upon him. When Robeson took a

vote, committee members Sherman and Mrs. Farragut chose Vinnie. The

frustrated Robeson relented and announced Vinnie as the winner.

By the spring of 1878, Vinnie completed her ten-foot model of the

Admiral. She depicted him on his 1862 bold attack on the forts

protecting New Orleans. In the summer of 1879 the statue would be cast

at the Washington Navy Yard. The statue and the four mortars on the

pedestal would be made from the bronze propeller of Farragut's flagship,

USS Hartford. The statue was dedicated on April 25,1881, the anniversary

of the day New Orleans surrendered. The ceremony took place in Farragut

Square in Washington, DC. Numerous military units marched up

Pennsylvania Avenue to the square. President and Mrs. Garfield attended

as well as many distinguished guests, including Mrs. Farragut. This was

President Garfield's first public address since his inauguration. John

Philip Sousa conducted the Marine Band. Amid a chorus of cheers, two of

Farragut's crew members hoisted the flag covering the work. Vinnie rose

to acknowledge the crowd's applause.

While working on the statue at the Washington Navy Yard, Vinnie met

wealthy Lieutenant Richard Hoxie of the Army Corps of Engineers, a West

Point friend of Farragut' s son. At the age of 31, Vinnie married Hoxie

in 1878. President Grant and most of the Senate attended the wedding and

Sherman even gave her away. The couple moved about the country as Hoxie

was transferred to new assignments. They had a son named Richard in

1883. Finally, they moved to 1632 K Street in Washington, D.C. near

Farragut Square and summered in Iowa City, Iowa. Hoxie asked Vinnie to

give up sculpting. Reportedly, Hoxie took her hand in his and said,

"These now belong to me. Your art work is ended . . . Now you must live,

not for the world, but for love and me." Vinnie said to an interviewer

that she gave up her career for love.

The moral attitudes of the Victorian Era frowned on wives working.

Vinnie became one of the most popular hostesses in the city. The Hoxie

home was a lively salon with guest that included congressmen, cabinet

members, military men and other dignitaries of the day. Vinnie often

played the harp and sang at gatherings. In 1887, Vinnie received a

letter from Sherman whose wife was ill. Hoxie also became ill at this

time. Sherman wrote "You have a sick husband and I a sick wife--I

sometimes think the Mormons are right and that a man should have the

right to change--tell Hoxie I will swap with him."

She

exhibited her works "America," "The West," and "Miriam,"

at the 1893 World Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Vinnie was diagnosed

with chronic kidney disease in 1903. Her husband and doctors thought

that she might recover more quickly if she were able to resume her

career. She began to sculpt as well as speaking to civic and women's

groups. She accepted a commission in 1906 to create a bronze statue of

the late Civil War governor of Iowa, Samuel J. Kirk, for Statuary Hall.

She was too weak to stand for long periods of time. Hoxie used his

engineering skills to design a "boatswain" chair that allowed her to sit

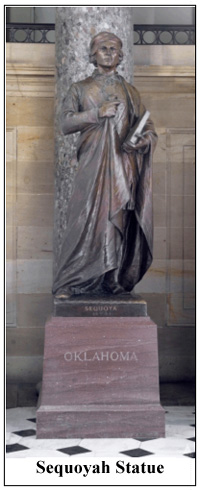

and work at all heights of the statue. In 1912, the state of Oklahoma

asked her to sculpt a statue of Sequoyah, the Cherokee leader who

developed a written alphabet for the Cherokee Nation, also to be placed

in Statuary Hall. The model was nearly finished but Vinnie collapsed.

She died on November 20,1914, at age 67. After Ream's death, her friend

and fellow sculptor George Zolnay cast her plaster model in bronze and

completed the monument. It was unveiled in 1917 -- the first

free-standing statue of a Native American to be placed in the National

Statuary Hall. She

exhibited her works "America," "The West," and "Miriam,"

at the 1893 World Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Vinnie was diagnosed

with chronic kidney disease in 1903. Her husband and doctors thought

that she might recover more quickly if she were able to resume her

career. She began to sculpt as well as speaking to civic and women's

groups. She accepted a commission in 1906 to create a bronze statue of

the late Civil War governor of Iowa, Samuel J. Kirk, for Statuary Hall.

She was too weak to stand for long periods of time. Hoxie used his

engineering skills to design a "boatswain" chair that allowed her to sit

and work at all heights of the statue. In 1912, the state of Oklahoma

asked her to sculpt a statue of Sequoyah, the Cherokee leader who

developed a written alphabet for the Cherokee Nation, also to be placed

in Statuary Hall. The model was nearly finished but Vinnie collapsed.

She died on November 20,1914, at age 67. After Ream's death, her friend

and fellow sculptor George Zolnay cast her plaster model in bronze and

completed the monument. It was unveiled in 1917 -- the first

free-standing statue of a Native American to be placed in the National

Statuary Hall.

Hoxie also asked Zolnay to sculpt a bronze bas-relief of his wife to

place on the grave site at Arlington National Cemetery. To crown the

memorial Hoxie had a bronze casting made of Vinnie's “Sappho,”

her favorite piece. The original “Sappho” is now in the

Smithsonian Institution. He wrote her epitaph “Vinnie Ream–Words That

Would Praise Thee are Impotent.” Vinita, Oklahoma was named in honor of

Vinnie Ream. Hoxie died in 1930 and was buried at Arlington with Vinnie.

There were times when Vinnie was concerned about the negative comments,

but she received great encouragement. Sherman once said to her,

“Lighting strikes at the tallest steeples.” Mrs. Farragut wrote, “Don't

be the least discouraged by adverse criticism, for it is impossible for

anyone to achieve greatness in any way without being a target to be shot

from a quiver of envy.”

Following a round of applause, our speaker answered many questions.

The following is part of a New York Times article, “The Lincoln Statue”

dated January 25, 1871: “Unveiling Miss Ream's Statue of the Late Mr.

Lincoln---Speeches by Prominent Members of Congress. Representative

Brooks of New York said, “It was appropriate that, in unveiling a statue

like this, a Democrat should be given an opportunity to express for

himself and associates their common interest both in the man and in the

monument ... He who acted so foremost a part as ... in that portion of

our history—the most exciting and most perilous, save that of our

revolutionary era–is entitled, not only to such a memorial as this, but

to have it placed here under the great dome of its Capitol. We have no

Parthenon, no Vatican, no Pinakothek [Munich museum] nor Westminster

Abbey, wherein to entomb our illustrious men or to erect statues to

their honor. Yet the time is coming, ... when this Rotunda, and the

surrounding halls and grounds, will be filled with pictures, paintings,

frescoes, statuary, bronzes, friezes, bas reliefs, and other monuments

of the world's memorable men. But the work here that we are unveiling is

the double memorial of not only a Chief Magistrate in the prime of life,

foully shot down, but the memorial of a women' s handiwork--a women's

plastic art. The Parthenon, the Vatican, the great museums of Paris,

London, and Berlin bring over to our eyes the works of some Phidias or

Praxiteles of antiquity, but they show us no marble monuments, busts or

statues the finger work of the fairer sex, while here in this Rotunda we

now see the equal rights of women, if not with the ballot, with the

pencil, to chisel, the artistic instruments, to perpetuate the human

form divine. Fortunate the man thus sculptured! ... for in a restored

Union ... he is thus forever consecrated to the Republic by his

martyrdom, immortalized among all mankind; fortunate, too, on being thus

handed down to posterity by a women's love of a noble art, one of the

few immortal names that were not born to die.

In the spirit of celebrating women artists, the following is from The

Philadelphia Inquirer, May 10, 2015:

A Poet, Up From Slavery

And mothers stood, with streaming eyes,

And saw their dearest children sold;

Unheeded rose their bitter cries,

While tyrants bartered them for gold.

And so began, “The Slave Auction,” a poem by one of America’s first

female African-American writers, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

(1825-1911). Born free in Baltimore, Harper was raised and educated by

her uncle, a teacher... Her formal education stopped at 14, but, working

as a maid in the home of a bookseller, she absorbed poetry and prose in

her off-hours. In 1850, she moved to Ohio. Her political and social

conscience was sharpened by a Maryland law forbidding free blacks from

entering the state without risking capture and sale into slavery.

Returning to Maryland impossible, she moved to New England. Her first

speech, Education and the Elevation of the Colored Race was so

successful the Maine Anti-Slavery Society hired her as a traveling

lecturer. Her writings expanded to the “intersections of all

oppression:” women’s rights, temperance and racial equality. In 1864,

she moved to Philadelphia. After the war, she continued to lecture

throughout the South. She is the author of Iola Leroy, or, Shadows

Uplifted, one of the first novels by an African-American woman.

Last changed: 08/30/15

Home

About News

Newsletters

Calendar

Memories

Links Join

|