The President’s Message:

Thank you to Robert

Franke for his donation of Civil War artwork, bonds, and currency.

Most of the collection has sold and the proceeds are now in our

treasury. I appreciated all

the assistance George and Morag Nimburg gave me at the Toy Soldier Sale

this weekend where many of the things were sold.

One picture will be in the raffle in February as well as a $30.00

gift card to Publix which was graciously donated by Doug Mogle.

A series of sketches

by well-known artist, B. Horton, are still available. They are numbered

and signed by the artist. The subjects include Robert Rodes, Longstreet,

Richard Taylor, Stonewall Jackson, Jeb Stuart, Benjamin Cheatham, Kirby

Smith, Joseph E. Johnston, A.P. Hill, P.G.T. Beauregard, and Nathan

Bedford Forest. If you would like to see this artistic, please call me

561/967-8911 or e-mail honeybell7@aol.com.

Please remember to

sign up on the Forage Sheet for refreshments. Every member is asked to

bring a refreshment once a year to a meeting.

Please pay your dues.

Gerridine LaRovere

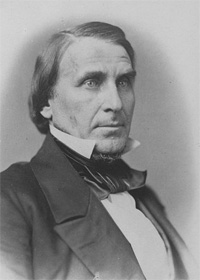

February 8, 2017 Program:

Our speaker is David Meisky who will present Confederate money.

A history graduate of George Mason University, Mr. Meisky retired

from the Fairfax County, Public Library. He has re-enacted for a number

of years and started appearing as “Extra Billy” Smith in the spring of

2008, after a good deal of study. He has also performed a first-person

portrayal of Captain David Meade, a Confederate army paymaster, which

allowed him to display and discuss his collection of period money. As an

infantry private, he has served for a number of years with the Fairfax

Rifles, Company D of the 17th Virginia Infantry Regiment.

January 11, 2017 Program:

Joseph Rose gave us an alternative view of Ulysses S. Grant in a talk

entitled

Grant Under Fire .

This is the same title of his over 800-page book of the same

name. This article was

taken directly from Joe’s speaking notes.

This accounts for the use of the first person.

This is a highly unpopular subject.

I’ll offer an

overview of Grant’s career in the American Civil War, highlighting

controversies which, when thoroughly investigated,

demonstrate how deficiencies in Grant’s generalship and in his character

detracted from the Union war effort.

Further, his unreliability as a writer detracts from the war’s

historiography. .

This is the same title of his over 800-page book of the same

name. This article was

taken directly from Joe’s speaking notes.

This accounts for the use of the first person.

This is a highly unpopular subject.

I’ll offer an

overview of Grant’s career in the American Civil War, highlighting

controversies which, when thoroughly investigated,

demonstrate how deficiencies in Grant’s generalship and in his character

detracted from the Union war effort.

Further, his unreliability as a writer detracts from the war’s

historiography.

Chronology:

As both a general and president Ulysses Grant had a tremendous impact on

the United States in war and in peace.

Many of his intentions and actions were indeed praiseworthy.

He was brave, persistent, and aggressive.

He had an extraordinary life.

The late Brian Pohanka once stated, however, “A lot of folks like

their Civil War history cut and dried, with a predictable cast of

characters–they like to cheer the hero and hiss the villain.

The curtain falls, and they say, ‘Very good, just as I remember

the play.’” Most of

history’s myths and mistakes about Grant are in his favor, and his

supporters have insisted, for over 150 years, that Grant’s writings are

truthful, and that he “won” the war.

But the devil is in the detail.

Washburne:

It is said: “Opportunity makes the man.” Grant had left the regular U.S.

army seven years earlier under a cloud of alcohol.

But the Civil War restarted his military career… through

politics. His congressman,

Elihu Washburne and other influential Illinoisans introduced Grant to

Governor Richard Yates, who finally made Grant colonel of an Illinois

regiment. In his second

inaugural address, Grant denied the importance of this political

support: “I did not ask for place or position, and was entirely without

influence or the acquaintance of persons of influence.”

He was doubly wrong.

During his tour around the world, he erroneously proclaimed: “When the

rebellion came I returned to the service because it was a duty.

I had no thought of rank.”

Actually, the former captain had refused anything he thought

inferior to a colonelcy and considered baking bread instead of fighting.

Before engaging in a single battle, Grant was promoted to

brigadier-general in the volunteer army at Washburne’s behest.

He ranked high on the official list, due to his previous service

in the regular army.

Luckily

assigned to Major-General John Frémont’s Western department, Grant was

only ranked by John Pope as a brigadier.

In

the Army of the Potomac, ten new brigadiers and several major-generals

would have ranked him. Washburne:

It is said: “Opportunity makes the man.” Grant had left the regular U.S.

army seven years earlier under a cloud of alcohol.

But the Civil War restarted his military career… through

politics. His congressman,

Elihu Washburne and other influential Illinoisans introduced Grant to

Governor Richard Yates, who finally made Grant colonel of an Illinois

regiment. In his second

inaugural address, Grant denied the importance of this political

support: “I did not ask for place or position, and was entirely without

influence or the acquaintance of persons of influence.”

He was doubly wrong.

During his tour around the world, he erroneously proclaimed: “When the

rebellion came I returned to the service because it was a duty.

I had no thought of rank.”

Actually, the former captain had refused anything he thought

inferior to a colonelcy and considered baking bread instead of fighting.

Before engaging in a single battle, Grant was promoted to

brigadier-general in the volunteer army at Washburne’s behest.

He ranked high on the official list, due to his previous service

in the regular army.

Luckily

assigned to Major-General John Frémont’s Western department, Grant was

only ranked by John Pope as a brigadier.

In

the Army of the Potomac, ten new brigadiers and several major-generals

would have ranked him.

John Aaron Rawlins:

For his new staff, Grant’s two aides-de-camp were inferior, drinking

men. But, Grant made no

mistake in choosing John Aaron Rawlins as assistant adjutant-general.

Among a host of accolades earned during the war, Grant and his

friends thought Rawlins was “absolutely indispensable,” “invaluable,”

one of the war’s “most admirable characters.”

“No one appreciated [him] more highly than” Grant.

Grant’s success was due to Rawlins’ “brains and good sense.”

“Rawlins was more necessary to Grant than Grant to Rawlins,” “Without

him Grant would not have been the same man,” “Rawlins is infinitely

Grant’s Superior.” And “without Rawlins there would have been no Grant.”

How did Grant reward Rawlins?

By almost entirely excluding the completely loyal, self-effacing

subordinate from his

Memoirs.

And Grant’s biographers also downplay Rawlins’ importance, even

adding insult to injury.

Geoffrey Perret declared that Rawlins “was a man incapable of loyalty.”

Even more obtusely, Bruce Catton protested that, “with a defender

like Rawlins, Grant had no need of any enemies.”

Grant likewise ignored his essential advocates Charles Dana and Elihu

Washburne in his

Memoirs,

while he turned the generally supportive

Henry Halleck into an adversary.

USS Tyler and USS St. Louis (later renamed the Baron de Kalb):

Another major component of Grant’s western successes was the Union’s

immensely powerful fleet of transports and gunboats.

These vessels were focused at the hugely

strategic riverport of Cairo, IL.

Here naval assets helped Grant obtain his all-important second

star early in the war.

Steam-driven transports moved and supplied his army and bases, while the

growing flotilla of woodenclads and ironclads overpowered enemy forts

and interrupted lines of communication.

Throughout the conflict, the Confederates could hardly compete

with the Union’s naval superiority, in coastal operations, through the

blockade, or on the western rivers.

Grant often did not reveal his reputed common sense or keen grasp of

strategy. Before being

assigned to Cairo he bemoaned, “I should like to be sent to Western

Virginia, but my lot seems to be cast in this part of the world.”

From Cairo, he wanted to descend the Mississippi although

ascending the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers was practical.

One reason: Any gunboat that became disabled while attacking a

fort downriver could drift down into the enemy’s hands, but in an

upriver attack it would float back to safety.

Paducah:

The first major incident of the war where Grant’s

Memoirs

are taken as literal truth, in spite of the evidence, is the occupation

of Paducah, KY. In early

September 1861, Confederate general Leonidas Polk breached Kentucky’s

self-proclaimed neutrality by occupying Columbus, where artillery

emplaced on the Mississippi’s bluffs could stop traffic heading

downriver. Well, if Polk

was foolish for doing this (and almost

everyone says so), then Frémont and Grant were foolish,

because they also wanted to do it.

Polk just beat them to it.

One of Frémont’s spies made it to Cairo and convinced Grant to

occupy Paducah ahead of the enemy.

The traditional story credits Grant with telegraphing Frémont for

permission, but setting off

before getting it. Although

the

Official Records

indicated that Grant received Frémont’s reply, historians apparently

overlook this. And none

seem to use Grant’s own lengthy, unsubmitted, report in the Library of

Congress. It states that

Grant received Frémont’s orders with authorization to occupy the town,

if possible, and that “I replied”

the same day. It’s a small

affair, but it’s proof of one in a long line of exaggerations and

untruths that pepper his

Memoirs.

Henry Halleck & Charles F.

Smith:

A West Pointer, Brigadier-General Charles F. Smith, came from the East

to take command at Paducah.

The authorities in Washington later removed department commander Frémont

and soon replaced him with Henry Halleck,

another

West Pointer, who was prejudiced against so-called “political generals.”

Grant wrote his wife on September 22nd

that “I would like to have the honor of commanding the Army that makes

the advance down the river, but unless I am able to do it soon cannot

expect it. There are too

many Generals who rank me that have commands inferior to mine for me to

retain it.”

Belmont:

Although he had distinct orders not to, Grant challenged the

Confederates in battle.

Escorted by two woodenclads, five transports took five regiments from

around Cairo downstream to a point opposite from the Confederate

stronghold of Columbus. The

one rebel regiment encamped at Belmont on the west bank was soon

reinforced by four more under Gideon Pillow.

Each side had a six-gun battery.

Although evenly matched, Grant’s infantry, helped by superior

artillery, pushed the Confederates back to their camp and overran it.

But Grant lost control of his men, while the enemy got away.

The Confederates took advantage of this interval by sending more

men across the Mississippi.

Now, Grant was forced to cut his way out and get back to the boats.

The retreat turned into a rout and the rear of the column

suffered severely. But with

the gunboats providing protection, the transports cut their hawsers and

steamed off just before enough Confederates arrived to annihilate the

federals. Grant escaped

with two Confederate cannon, and he had inflicted somewhat more

casualties than he suffered.

But he also left his wounded, many weapons, and much equipment on

the battlefield.

Grant informed headquarters that the “victory was complete.”

He told his wife and his father that it was “most complete.”

But his actions afterward belied such claims.

He pulled back a column in Missouri that was to have joined him.

In 1864, Grant compiled an expanded report of the battle.

It amounted to a forgery.

It was backdated to November 17, 1861, ten days after the

original, it had an anachronistic heading and addressee,

and Lieutenant-General Grant signed it “Brigadier-General Grant.”

He further added two outright fabrications in an attempt to

justify his insubordination in attacking.

Thomas A. Scott said

“It appears strange that officers, having an eye to the interests of the

Government, could in such a manner countenance, much less certify to,

such injustice,”

Cairo:

Over and over, his biographers stated that Grant was not personally

corrupt. But, back in Cairo

two ringleaders led a regime of fraud.

Grant’s assistant quartermaster, Reuben Hatch, brother of one of

the Illinois politicians who helped secure Grant’s colonelcy, and George

Washington Graham, Grant’s commodore of river boats clearly were

corrupt. This encompassed

bread, lumber, cordwood, shingles, ice, coal, oats, hay, and, river

boats. Grant admitted “the

great abuses,” but supposedly wanted to investigate further, while he

stalled Hatch’s court martial.

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton sent an eminent committee, which

verified the “gross fraud.” Assistant Secretary of War Scott did also

and, after examining the books, thought it strange that army officers

would certify such corruption.

He noted that William Kountz came to replace Graham and look into

the boat and coal contracts.

“In a very short time his explorations appeared to trouble the

Commanding Officer [Grant] who placed him under arrest.” Graham was

reinstated.

And Grant’s delays in prosecuting Reuben Hatch apparently gave Illinois

politicians enough time to convince President Lincoln to handpick an

auditing committee: Charles

Dana (who became a strong Grant supporter), George Boutwell (Grant’s

future Secretary of the Treasury), and Stephen Cullom (John Rawlins’

classmate and good friend).

The author of

The Sultana

Tragedy: America's Greatest Maritime Disaster,

wrote, “It is not surprising that Lincoln’s hand-picked

commission acquitted Hatch of all blame.” The committee implicitly

exculpated Graham and Grant’s administration at Cairo, as well.

Reuben Hatch later returned to Grant’s staff as Chief

Quartermaster and Grant glowingly endorsed a recommendation to Lincoln

for Hatch’s promotion, saying he was wrongfully accused, “without a

fault being committed by himself” and a “full investigation has entirely

exonerated him.” Later,

Grant pushed him as master of water transportation at New Orleans.

But when Hatch got a job in 1865 as a quartermaster along the

Mississippi, he overloaded the transport

Sultana

with recently

freed Union prisoners. The

boat exploded and the sixteen hundred to eighteen hundred victims

approximated the federal death-toll at Shiloh.

Grant’s favoritism had its costs, sometimes monetary, sometimes

human. Andrew Foote has

said: “I strongly objected to open on Fort Donelson when we did as by

waiting three days, as I wanted to do, we could have brought four mortar

boats, and shelled out the Fort and troops, with the saving of hundreds

of valuable lives.”

Fort

Henry:

Grant tried, in his

Memoirs,

to make Henry Halleck appear unsupportive of a movement up the Tennessee

and Cumberland Rivers.

Actually, both of them and naval officer Andrew Foote favored such a

plan. Although Grant

initially “preferred” to assault Fort Donelson on the Cumberland, he

yielded to Foote, who proposed attacking Fort Henry first.

A small armada steamed up the Tennessee in early February 1862.

While planning the combined attack, Foote advised that the

infantry start before the gunboats.

Grant refused. So,

by the time that Foote’s four ironclads, backed up with three

woodenclads, had shelled Fort Henry into submission, the infantry was

still a long way off. This

allowed almost the whole garrison to escape to nearby Donelson.

Ironically, many authors credit Grant alone for a victory won by

the navy. Fort

Henry:

Grant tried, in his

Memoirs,

to make Henry Halleck appear unsupportive of a movement up the Tennessee

and Cumberland Rivers.

Actually, both of them and naval officer Andrew Foote favored such a

plan. Although Grant

initially “preferred” to assault Fort Donelson on the Cumberland, he

yielded to Foote, who proposed attacking Fort Henry first.

A small armada steamed up the Tennessee in early February 1862.

While planning the combined attack, Foote advised that the

infantry start before the gunboats.

Grant refused. So,

by the time that Foote’s four ironclads, backed up with three

woodenclads, had shelled Fort Henry into submission, the infantry was

still a long way off. This

allowed almost the whole garrison to escape to nearby Donelson.

Ironically, many authors credit Grant alone for a victory won by

the navy.

Ft. Donelson:

Although he did not know how many troops were at Fort Donelson or who

commanded them, Grant aggressively led his army over to the Cumberland,

where he almost surrounded the fort.

Hoping for a repeat of Fort Henry, Grant unwisely pushed a more

cautious Foote into a premature naval attack.

It failed, as Confederate artillery knocked out several

ironclads.

I really wish we knew what Grant was doing when he went to visit the

wounded Andrew Foote early the next morning.

He was off the field and out of touch for about six hours.

Grant left no orders in his absence, except for his three

divisions to maintain their positions, and apparently didn’t empower his

staff to act in his stead.

Knowing that they had to break out or surrender, and having backpedaled

on an attack the day before when they had a much greater chance, the

Confederates assaulted McClernand’s open right flank early in the

morning. Without support

and running out of ammunition, McClernand’s division was driven back.

His requests for reinforcement went unheeded at headquarters, and

Grant was gone. Before McClernand’s division completely shattered, Lew

Wallace insubordinately sent him a brigade.

That was insufficient.

Again, Wallace acted against orders bringing artillery and most

of his remaining men to stop the enemy, and he did.

Instead of escaping when they had the chance, the Confederates

returned to their entrenchments.

After noon, Grant finally arrived on the battlefield and ordered

attacks on both flanks. The

Confederates, penned up and with truly incompetent commanders,

surrendered the next day.

It was a great victory and Halleck congratulated both Grant and Foote,

and he pushed for Grant’s promotion to major-general of volunteers, thus

placing Grant very high up the army rankings.

In most narratives, Andrew Foote doesn’t share in the credit for

this victory.

Soon after the battle, Halleck became annoyed at Grant for three things.

His relatively undisciplined army was plundering Fort Donelson,

while many captured Confederates escaped by merely walking through the

lines. Grant left his army

and cruised up the Cumberland River to visit newly captured Nashville

and see Don Carlos Buell, commander of the Union department to the east

of Halleck’s. Lastly, he

didn’t provide Halleck with reports of his army’s strength.

On top of everything, there were indications he had been drinking

again.

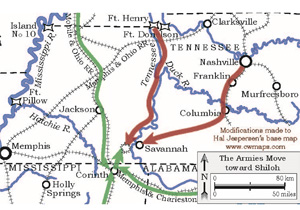

Shiloh:

Because of this, Halleck placed

Charles Smith in charge of the expedition heading south up the Tennessee

River, even though John McClernand was the next ranking officer.

But Halleck was not Grant’s jealous tormentor, as many historians

suppose, and he soon put Grant back in command.

Grant started out well enough, concentrating all but one of his

divisions around Pittsburg Landing and Shiloh Church.

The Confederates, meanwhile, were gathering strength under Albert

Sidney Johnston at Corinth twenty miles away… one good day’s march.

Grant wanted to advance, but was restrained by Halleck, who now

also commanded Buell, who was ordered to join Grant for a unified

advance. Staying in a

mansion at Savannah, ten miles downriver and on the opposite bank, Grant

neglected his army and ignored proper precautions, especially as he

believed that the Confederates him about two to one.

He stopped sending out spies, scouts, or patrols; he didn’t place

cavalry vedettes in front of the camp; he placed the newest, least

experienced divisions at the front (or he let who was in

de facto command do it); he didn’t emplace

artillery, he switched his artillery and his cavalry among the

divisions; he transferred some commanders for personal reasons; and he

didn’t entrench or construct entanglements or clear fields of fire.

Albert Sidney

Johnston:

Consequently, his army was surprised

and seriously unprepared when Albert Johnston’s Confederates attacked on

April 6th.

Only brigade commander Colonel Everett Peabody’s insubordinate

decision to send out a patrol early that morning prevented a total

surprise. The first day’s

battle nearly

ended up being a catastrophe and

Peabody’s action, by itself, may have saved Grant’s army.

Before battle: Grant, on the other hand, committed

mistake after mistake, as the battle began.

He was still residing at Savannah, on the day before battle, when

he postponed meeting General Buell, the supposed reason for being away

from his army. And he

refused to forward Buell’s advance division, under William Nelson, to

Pittsburg Landing, as he said it couldn’t march through the swamps along

the east bank of the Tennessee.

When Grant heard cannon-fire sometime after 7:00 the next

morning, he ordered Nelson to march through

those swamps.

Grant said that Nelson could easily find a guide, but none was

located until noon. After

merely notifying Buell that a battle had begun, Grant hurried upriver on

his flagship

Tigress.

Going upstream: His next mistake came at Crump’s

Landing almost halfway to the battlefield.

Tigress stopped long enough for Grant to

confirm that the battle was at Pittsburg Landing, but he only directed

Lew Wallace to be ready to march in any direction.

Further along, a steamboat came down with news of the battle.

Grant ignored the opportunity to send it further downriver to

alert Lew Wallace and Buell that their troops would be needed.

Upon reaching Pittsburg Landing around nine o’clock, Grant rode

up the bluff and met William Wallace, another of his division

commanders. Although Grant

claimed that he immediately sent

Tigress back with instructions for Lew

Wallace to march to Pittsburg Landing, that can hardly be true.

His messenger, going downstream on

Tigress, did not reach Lew Wallace until

11:30. Grant probably didn’t

give his orders until around 10:00 o’clock.

Again, he ignored the opportunity to have the boat continue to

Savannah to inform Buell and bring up some of his men.

Grant seemed willing to jeopardize the battle by keeping Buell

out of it. The orders Lew

Wallace received directed him to the right of the army flank (not to

Pittsburg Landing), and Wallace’s Division, after a half-hour lunch, set

out on the Shunpike, a route that they had corduroyed and bridged.

By the time that they had reached the bridge one of Grant’s staff

arrived and informed Wallace that Sherman had been driven back and they

would be behind enemy lines if they kept going.

So, Wallace backtracked to the river road to the battlefield.

His division arrived around sunset, and Grant turned him into a

scapegoat once the country had heard the news about the army’s surprise

and near

defeat.

Shiloh battlefield: Grant’s

Memoirs allege that, “During the whole of Sunday I was continuously engaged in

passing from one part of the field to another, giving directions to

division commanders.” This, also, is untrue. Stephen Hurlbut complained

that Grant gave him no orders.

Sherman repeatedly recalled how Grant gave him no orders.

Grant didn’t even see John McClernand.

Grant’s dealings with William Wallace are unknown, as

Wallace was mortally wounded, but

none of Wallace’s three brigadiers indicated any orders from Grant.

In the Hornet’s Nest, Benjamin Prentiss was ordered to hold at

all hazards. That seems the

extent of Grant’s continuously giving directions to division commanders;

except for one time more. Shiloh battlefield: Grant’s

Memoirs allege that, “During the whole of Sunday I was continuously engaged in

passing from one part of the field to another, giving directions to

division commanders.” This, also, is untrue. Stephen Hurlbut complained

that Grant gave him no orders.

Sherman repeatedly recalled how Grant gave him no orders.

Grant didn’t even see John McClernand.

Grant’s dealings with William Wallace are unknown, as

Wallace was mortally wounded, but

none of Wallace’s three brigadiers indicated any orders from Grant.

In the Hornet’s Nest, Benjamin Prentiss was ordered to hold at

all hazards. That seems the

extent of Grant’s continuously giving directions to division commanders;

except for one time more.

Grant’s

Memoirs blamed Prentiss for not falling

back during “one of the backward moves” leaving his flanks exposed which

“enabled the enemy to capture him with about 2,200 of his officers and

men.” But there were no coordinated backward moves, and Prentiss had

been ordered to hold fast.

Even worse, by 4:00 pm the Confederates had enveloped both ends of the

Hornets’ Nest and the Union supporting divisions on both flanks were

heading toward the rear.

Prentiss, in a speech that Grant’s

Memoirs

vouched for as correct, remarked

that “Grant knows that I communicated to him at 4 o’clock at the

landing, and tried to get re-enforcements, and received orders to hold

on. I held.” So, Grant, not

Prentiss, was responsible for allowing the Confederates to capture these

troops. And Grant didn’t

bother to note that, if Prentiss had been culpable for not retreating in

time, so was his friend William Wallace.

Except negatively, General Grant seemingly had little impact at

the brigade and division levels on the first day of the battle, nor did

he have much on the second day.

Pushed back towards the river, Grant

was reinforced by Lew Wallace and joined by three of Buell’s divisions.

The next day, the two armies drove the Confederates off the field

and in retreat back to Corinth.

Although authorized to do so, Grant never took command over Buell

and his army.

Afterward, Grant claimed victory

and, “As to the talk of a surprise here, nothing could be more false.

If the enemy had sent us word when and where they would attack

us, we could not have been better prepared.” Although all of the Union

division commanders performed well, Grant showed his favoritism by

showering praise on William Sherman, who was likewise responsible for

both the surprise and the lack of preparations.

[Ed. note:

At this point Mr. Rose describes Vicksburg in some detail and

other side stories to illustrate his premise.

Space does not allow me to reproduce it here.]

Chattanooga:

Chattanooga, Tennessee, has been

called a natural amphitheater.

From the perspective of the Army of the Cumberland defending the

city, Missionary Ridge stretches on the east, with a roughly 45-degree

slope up to the crest, some three hundred feet high.

To the west, Lookout Mountain looms over twelve hundred feet

above the railroad, road, and river routes into Chattanooga from

Union-held areas.

Bragg’s Army of Tennessee occupied

both of these heights and breastworks lined the foot of the ridge and

curved over toward Lookout With the river and the rugged Cumberland

Plateau behind them, and only one tenuous route for supplies, the Union

troops were in a precarious position.

Before Grant reached town, Rosecrans and William (Baldy) Smith

planned operations to open up a new route for supplies, the “cracker

line,” and it was put on foot by General Thomas the very evening he was

promoted. Grant concurred

upon his arrival days later.

Directed by Thomas, Smith,

and Joseph Hooker, who was sent from

the East with the small 11th and 12th Corps to prevent catastrophe, it

worked to perfection. Troops

silently floated down the river a pontoon bridge was laid at Brown’s

Ferry and Hooker came in from the west. But disliking these four

officers, Grant seized their laurels: “I issued orders for opening the

route to Bridgeport,” and “in five days from my

arrival in Chattanooga the way was

open.”

Sherman and four divisions of Grant’s old

Army of the Tennessee marched from northern Mississippi to be part of

the upcoming battle. Grant’s

plan gave Sherman the starring role, put Thomas in support, and tried to

keep Hooker

out of the fight.

That didn’t happen when Sherman’s trailing division

couldn’t cross at Brown’s Ferry.

So, Thomas told Hooker that he could attempt to take the slope of

Lookout Mountain. On

November 24th, Hooker did so in spectacular

fashion—the Battle Above the Clouds, but “there was no such battle,”

Grant insisted; “It is all poetry.” Usually, a commander praised his

successful subordinates, but not Grant.

Not if he didn’t like you.

Meanwhile, Sherman muffed his surprise crossing upstream.

He started late, didn’t dash to the ridge as planned, and he

stopped too soon. Grant still commended Sherman’s efforts.

Although Hooker was now in position

to join the attack against Missionary Ridge, Grant sent him to the top

of now-abandoned Lookout Mountain, seemingly willing to jeopardize the

battle by keeping Hooker out of it, but Thomas ordered Hooker forward.

On the 25th, Sherman performed even worse than

before. Although Grant gave

him all the troops he wanted and more, Sherman utterly failed to dent

the enemy defenses with his piece-meal attacks.

To help his friend win the battle, not knowing that Sherman was

stopping for the day, Grant foolishly ordered a demonstration by some of

Thomas’ divisions to take the rifle-pits at the base of Missionary

Ridge, which would put them in an untenable situation under the guns on

the crest. Thomas delayed

for an hour, and when Grant forced the issue, the men went forward.

But from this indefensible position they kept going, up the

ridge, scattering the defenders, and winning a glorious victory, with

help from Hooker who did great work flanking the enemy on the right.

Grant and his biographers claim that he meant to ascend the

ridge, just in two steps.

But the evidence leaves no doubt that he merely wanted a demonstration

in Sherman’s favor.

Reporter Sylvanus Cadwallader, in

his later manuscript, was maybe the only person on Orchard Knob who

echoed Grant’s version. But,

in an article written that very evening for the

Chicago Times, which historians

seem to know about: “Division

commanders were especially instructed to make no attempt to ascend,” but

when the officers couldn’t restrain the men, “whole regiments began to

dash up the slope of the ridge, in positive disobedience to orders.”

In the charge up Missionary Ridge,

Grant displayed his lack of tactical ability, his gross favoritism, and

his unreliability as an historian in one stroke.

He lionized Sherman and Sheridan, at the expense of Hooker,

Granger, and Thomas.

Overland campaign:

The rest of the war amply confirmed

these deficiencies in Grant’s generalship and in his character.

During the Overland campaign his blatant favoritism in giving

protégés Phil Sheridan and James Wilson cavalry commands backfired.

And there was no need to do this.

Five times, Grant maneuvered. Five times his movements failed.

He failed to get through the Wilderness to open country; he

failed to reach Spotsylvania first; he failed to get over the North Anna

safely; he failed to get his army to Cold Harbor before the enemy could

fortify; and he failed to move on Petersburg with his entire force to

ensure that town’s capture.

Five times Grant went to battle— at

the Wilderness; Spotsylvania; North Anna; Cold Harbor; and Petersburg,

and didn’t come close to beating Robert E. Lee, despite having an almost

two-to-one advantage in manpower, with better artillery, better cavalry,

and much better logistical support. He lost the next two battles in a

row, as well: at Jerusalem Plank Road and the Crater. Over and over

Grant ordered frontal assaults, in terrible terrain, against

fortifications, all along the line, impetuously, and with little

planning. He wore out and

used up the Army of the Potomac.

In the end, the Confederacy died of exhaustion far more than from

Grant’s strategy or tactics.

Last changed: 01/26/17

Home

About News

Newsletters

Calendar

Memories

Links Join

|