The President’s Message:

Mark your calendars and save the date on

September 13th the Round Table will be celebrating our 30th

Anniversary. This is a tremendous achievement and every member

should be proud.

There will be an extra special raffle.

Please bring any Civil War memorabilia that you are willing to donate

including books, paintings, artwork, newspaper, etc.

Please bring any friends or guests to our

celebration.

Gerridine LaRovere

August 9, 2017 Program:

LTC (Ret.) Harold Knudsen is an

Illinois native. His career

spans twenty five years of active duty Army service, and includes seven

resident career artillery, command and staff Army schools and colleges.

He has many years of tactical experience in the integration of

fire support into maneuver plans and fire control computation for cannon

units. He spent nine years

in Germany training tactics offensive armored warfare, as well as

peace-keeping and counter-insurgency training.

A combat veteran of Desert Storm, he performed extensive

artillery fire planning and execution in support of the US breakthrough

of the Iraqi line and penetration into Iraq.

He has also served in the Iraq Campaign.

His years of staff work at the Corps, Army, and Pentagon levels

give him a strong understanding of army operations from the lowest to

highest levels. His book:

General James Longstreet the

Confederacy’s Most Modern General, draws heavily from 20th Century

Army doctrine, field training, staff planning, command, and combat

experience.

July

12, 2017 Program:

Our

speaker was Josh Liller. He

is the collections management at the

Jupiter Inlet

Lighthouse and Museum

. Supervision of

archives staff, interns, volunteers, and visitors.

Duties include cataloging, data entry, organization, inventory,

research, lectures/presentations, visitor tours, and generating content

for social media and newsletters.

Research includes answering staff and visitor questions,

conducting oral history interviews, and expanding collection content and

knowledge. Our

speaker was Josh Liller. He

is the collections management at the

Jupiter Inlet

Lighthouse and Museum

. Supervision of

archives staff, interns, volunteers, and visitors.

Duties include cataloging, data entry, organization, inventory,

research, lectures/presentations, visitor tours, and generating content

for social media and newsletters.

Research includes answering staff and visitor questions,

conducting oral history interviews, and expanding collection content and

knowledge.

Congress created the US Lighthouse Establishment (USLHE) with the 9th act of their first

session in 1789 and placed it in the Department of Treasury.

The USLHE was responsible for all Aids to Navigation, not only

the operation and maintenance of lighthouses and lightships, but also

beacons (lighted and unlighted), range lights, channel markers, buoys,

and fog signals. For more

than half a century the USLHE lacked good, dedicated management.

Congress finally created a temporary Lighthouse Board in 1851 to

deliver a detailed report about the state of US lighthouses.

A year later, the Board delivered an extensive report to

Congress, nearly 800 pages in length.

Congress made the Board a permanent organization to manage the

USLHE.

The permanent

Lighthouse Board consisted of the Secretary of the Treasury, several

Army engineer officers, several Navy officers, and several civilian

scientists. It included a

Chairman, Naval Secretary, and Engineering Secretary.

The Board overhauled the USLHE from top to bottom, including

better regulation, instruction,

and inspection of lighthouse keepers.

They created a District system that divided the Atlantic, Gulf,

and Pacific Coasts plus the Great Lakes and Mississippi River system,

into manageable areas. Each

district had an Engineer and an Inspector.

The Engineer, normally an Army officer from the Corps of

Engineers or Topographic Engineers, selected the sites for new

lighthouses, designed new and renovated existing lighthouses and other

light station structures, and supervised construction or designated a

project supervisor.

Inspectors, usually a Navy officer, made quarterly inspections of each

light station, investigated complaints, and generally handled personnel

and supply issues.

Given the small size

of the antebellum US military and West Point's vital role in training

engineers, it should come as no surprise that many prominent Civil War

officers served as District Engineers or Inspectors and/or members of

the Lighthouse Board prior to the Civil War.

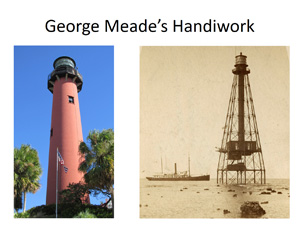

George

Meade is probably both the best-known example and arguably the most

significant. His Civil War

activities need no explanation.

Between 1852 and 1856 he served as District Engineer for the 4th

(NJ and Delaware Bay) and 7th (Florida) Districts, and also for about a

year as 5th District Engineer (VA & NC).

In Palm Beach County, he is well remembered for selecting the

site for and creating the initial design of Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse.

He also created the original designs for Absecon, Barnegat, and

Cape May Lighthouses in New Jersey; designed improvements for the Cape

Henlopen Lighthouse that used to stand on the west side of the mouth of

Delaware Bay; improved the Cape Florida Lighthouse; supervised

construction of the Carysfort Reef Lighthouse off Key Largo; designed

Sombrero Key Lighthouse off Marathon; designed and supervised the

construction of Sand Key and Northwest Passage Lighthouses near Key

West; and designed Cedar Keys Lighthouse on the Florida Gulf Coast.

He also invented the Meade Illuminating Apparatus, an improved

oil lamp for lighthouses that came to be widely used.

Meade's successor, William F. Raynolds, improved the designs for

Jupiter, Absecon, Barnegat, and Cape May and served for a short time on

the Army of the Potomac's staff. George

Meade is probably both the best-known example and arguably the most

significant. His Civil War

activities need no explanation.

Between 1852 and 1856 he served as District Engineer for the 4th

(NJ and Delaware Bay) and 7th (Florida) Districts, and also for about a

year as 5th District Engineer (VA & NC).

In Palm Beach County, he is well remembered for selecting the

site for and creating the initial design of Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse.

He also created the original designs for Absecon, Barnegat, and

Cape May Lighthouses in New Jersey; designed improvements for the Cape

Henlopen Lighthouse that used to stand on the west side of the mouth of

Delaware Bay; improved the Cape Florida Lighthouse; supervised

construction of the Carysfort Reef Lighthouse off Key Largo; designed

Sombrero Key Lighthouse off Marathon; designed and supervised the

construction of Sand Key and Northwest Passage Lighthouses near Key

West; and designed Cedar Keys Lighthouse on the Florida Gulf Coast.

He also invented the Meade Illuminating Apparatus, an improved

oil lamp for lighthouses that came to be widely used.

Meade's successor, William F. Raynolds, improved the designs for

Jupiter, Absecon, Barnegat, and Cape May and served for a short time on

the Army of the Potomac's staff.

Other notable Union

generals with prewar lighthouse experience: William F. "Baldy" Smith (11th District Engineer

1856-1859 and Board Engineer Secretary 1859-1861), William B. Franklin

(Engineer Secretary 1857-1859, 1st District Engineer

1852-1860, and 2nd District Engineer

1856-1860), Henry Halleck (Engineer and Inspector of the 12th District

in California 1852-1854), William Rosecrans (3rd District Engineer

1852-1853), John G. Parke (Engineer Secretary 1856-1857), and John Pope

(11th District Engineer 1860-1861).

On the Confederate

side, William Henry Chase (W.H.C.) Whiting served as 6th District

Engineer and in "special duty" (defacto Assistant Engineer) in the 5th

District from 1856-1861. His

most prominent project was the design and construction of the Cape

Lookout Lighthouse. During

the war, he is best known for engineering Fort Fisher near Wilmington.

Naval officers were

also involved. Samuel DuPont

is best remembered as commander of the South Atlantic Blockade Squadron

during the first half of the war, but from 1852 to 1857 he was a key

member of the Lighthouse Board.

Raphael Semmes was the 8th District Inspector (Gulf Coast)

1857-1858 then Lighthouse Board Naval Secretary until his resignation on

the eve of the war. Semmes served briefly as the head of the Confederate

Bureau of Lighthouses, but quickly sought a more active role.

He famously commanded the commerce raiders CSS Sumter and CSS

Alabama.

Semmes was the only active member of the Lighthouse Board to join the

Confederacy. William

Shubrick, the Lighthouse Board Chairman from 1862 to 1871 (except for a

few months in 1859), was born in South Carolina, but had served in the

US Navy since 1806 and his allegiance was firmly with his country over

his home state.

Seceding states were

quick to disable their lighthouses, in some cases even before the firing

on Fort Sumter. North

Carolina's governor ordered the extinguishing of lighthouses even before

his state had formally seceded.

Of 367 lighthouses, lightships, and lighted beacons active in the

United States on January 1, 1861, 177 of those light stations were

located in the seceding states (from Texas to Virginia).

164 of these were disabled, damage, or destroyed.

The lighthouses of the Florida Keys and a few in Virginia (the

Eastern Shore, Fortress Monroe, and near Washington) were the only

exceptions. In should be

noted that every one of these were Federal property - they were owned,

operated, maintained, and (with only a couple exceptions) build by the

Federal government not the states.

Many had been built in the decade preceding the war and thus were

nearly brand new at the time of their destruction.

Particularly

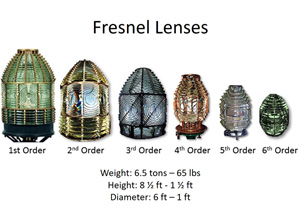

affected by the war were Fresnel lenses.

Ranging from massive 1st order lenses in major landfall

lighthouses to small 6th order lenses in harbor and range lights,

Fresnel lens had been invented by Augustin Fresnel, a French physicist

and engineer, only a few decades earlier and were eventually used

throughout the world. Every

Fresnel lens in America in 1861 had been manufactured in France and

nearly all were installed in the decade prior to the war at great

expense to the Federal government.

At the time, each 1st order lenses cost the equivalent quarter

million dollars in today's money (and would cost roughly $7 million to

replicate today). Of the 164

lights, nearly every one of them had their Fresnel lens removed.

The expensive and fragile lenses were mostly removed by people in

too much of a hurry and not properly trained in their handling, packing,

and care. As a result, the

lenses had to be repaired, usually requiring shipment back to the

manufacturer in France. Many

major lighthouses had to temporarily use a smaller lens until their

normal lens could be repaired or replaced. Particularly

affected by the war were Fresnel lenses.

Ranging from massive 1st order lenses in major landfall

lighthouses to small 6th order lenses in harbor and range lights,

Fresnel lens had been invented by Augustin Fresnel, a French physicist

and engineer, only a few decades earlier and were eventually used

throughout the world. Every

Fresnel lens in America in 1861 had been manufactured in France and

nearly all were installed in the decade prior to the war at great

expense to the Federal government.

At the time, each 1st order lenses cost the equivalent quarter

million dollars in today's money (and would cost roughly $7 million to

replicate today). Of the 164

lights, nearly every one of them had their Fresnel lens removed.

The expensive and fragile lenses were mostly removed by people in

too much of a hurry and not properly trained in their handling, packing,

and care. As a result, the

lenses had to be repaired, usually requiring shipment back to the

manufacturer in France. Many

major lighthouses had to temporarily use a smaller lens until their

normal lens could be repaired or replaced.

In Virginia,

Confederates raided some of the Eastern Shore and Chesapeake Bay lights

that had remained active or were restored early in the war.

An 1863 raid destroyed the original Cape Charles Lighthouse and

wrecked the construction site for a new tower being built there.

Construction resumed and was successfully completed in 1864, but

necessitated a company of Union soldiers on guard duty.

A raid on Blackistone Island Light in 1864 broke the lens and

lamps; the lighthouse itself only survived because the keeper's wife was

in labor in the house. The

light was repaired and a gunboat was assigned to guard the island to

prevent the raiders' return.

In North Carolina,

Gov. Ellis ordered the state's lighthouses to be darkened before the

state had formally seceded.

The most important of these was Cape Hatteras which guarded the

dangerous Diamond Shoals. Burnside's expedition to capture the Outer

Banks in early 1862 aimed at stopping Confederate commerce raiders and

closing off Confederate ports to blockade runners, but also had the

important goal of enabling the lighthouse to be relit.

(Note this is not the same Cape Hatteras Lighthouse that stands

today.) Confederates

unsuccessfully attempted to blow up the Cape Lookout Lighthouse in 1864,

but only succeeded to taking out part of the staircase.

The Bogue Bank Rear Range Light, which helped guide ships into

Morehead City and Beaufort, was torn down by Confederates at Fort Macon

to give the fort a clear field of fire.

In South Carolina, Gov. Pickens not only disabled all of the lighthouses

in the state, but also seized the lightships, and lighthouse tenders

based out of Charleston. In

Dec 1861, Confederates blew up the Charleston Lighthouse on Morris

Island, one of the few remaining from colonial times.

A small lighthouse on one of Fort Sumter's bastions served as a

range light before the war and was reduced to rubble during the war

along with most of the rest of the fort.

When the Union Navy captured the islands east of Charleston early

in the war, they found the lighthouses there badly damaged by

Confederates; Cape Romain's lantern and lens were described as

"ruthlessly destroyed" and at the small Bull's Bay Lighthouse they found

"everything recklessly broken, down to the oil cans."

The Hunting Island Lighthouse near Port Royal was also blown up.

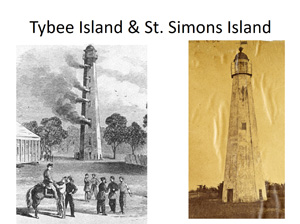

In Georgia,

retreating Confederates set a fire that badly damaged the Tybee Island

Lighthouse near Savannah and blew up the St. Simons Island Lighthouse near Brunswick.

The small Cockspur Island Lighthouse was in the life of fire for

the Union's devastating bombardment of Fort Pulaski, but fortunately was

not hit.

Savannah and blew up the St. Simons Island Lighthouse near Brunswick.

The small Cockspur Island Lighthouse was in the life of fire for

the Union's devastating bombardment of Fort Pulaski, but fortunately was

not hit.

In Florida, the Union

Navy had to keep gunboats guarding the Florida Reef lights.

The war delayed the construction of a new brick-and-iron tower at

Cape Canaveral. It was not

built until 1868. The new

lighthouse’s iron plates were manufactured by Robert Parrott's West

Point Foundry that also made Parrott Rifled Artillery.

At Jupiter, assistant keeper Augustus Oswald Lang gathered

several Indian River residents to chase off the head keeper and disable

the light. Contrary to

longstanding stories, Jupiter's Fresnel lens was almost certainly left

in the lighthouse during the war, but the lamps, fuel, and other

supplies were hidden along the Indian River.

Lang and his compatriots also visited the Cape Florida Lighthouse

on Key Biscayne where they not only took supplies, but also smashed part

of the Fresnel lens. Both

Jupiter and Cape Florida were repaired in 1866. Egmont Key Lighthouse in

the mouth of Tampa Bay served as a refuge for Southern Unionists and

runaway slaves, and a supply depot for the Union Navy.

In the Florida Panhandle, Confederates established a gun battery

at St. Marks Lighthouse near Tallahassee.

The Union Navy twice bombarded the battery and lighthouse; after

the Confederates withdrew, the Navy burned the lighthouse's wooden

staircase so the tower could not be used as a lookout station.

In early 1865, the Union Army landed at the lighthouse and

advanced on Tallahassee, but was turned back at the Battle of Natural

Bridge. Someone tried

unsuccessfully to blow up the lighthouse near the end of the war; it

remains unclear whether the Union or Confederates were to blame.

Pensacola Lighthouse was struck by several cannonballs fired by Fort

Pickens during a fierce artillery battle in 1861.

Fortunately, the damage was no serious.

In Alabama, the Union

captured Sand Island Lighthouse at the entrance to Mobile Bay.

In addition to relighting it as an aid to navigation, they used

it to spy on nearby Fort Morgan. Lt. John W. Glenn led a raid from the

fort in Jan 1863 that burned the lighthouse stairs.

Glenn returned the next month to finishing the job, blowing the

tower to pieces with 75 lbs. of gunpowder.

He wrote of the lighthouse's destruction to the Chief Engineer of

the Confederate District of the Gulf, Danville Ledbetter.

Ledbetter's reaction is unknown, but it must have been

bittersweet news: he had designed the lighthouse less than a decade

earlier. The Mobile Point

Lighthouse at Fort Morgan was several damaged by gunfire from Farragut's

fleet during the Battle of Mobile Bay.

In Mississippi, several lighthouses were burned, including Ship Island.

The island was occupied by the Union Navy as a blockade station

and the lighthouse was rebuilt.

Legend claims the iron Biloxi Lighthouse was painted black in

mourning after Lincoln's assassination, but this is a myth.

In Louisiana, each of

the three main Mississippi River Delta passes had a major lighthouse.

The Union Navy was able to get 2 of the 3 Fresnel lenses before

the Confederates could. The

small lighthouses on Lake Pontchartrain remained active until Farragut's

attack. One Louisiana

lighthouse keeper was murdered during the war shortly after his

lighthouse was relit by the Union; he was the only lighthouse keeper to

die on duty because of the war.

The Sabine Pass Lighthouse in the southwest corner of the state

was used frequently by both sides as an observation post.

On at least two occasions, small skirmishes broke out when one

side arrived while the other was still present.

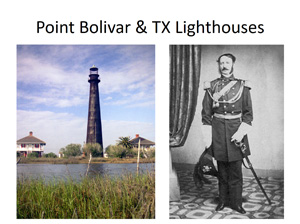

In Texas, the

original Bolivar Point Lighthouse was disassembled for its iron.

A new iron lighthouse was built after the war and it withstood

the devastating Galveston Hurricane of 1905.

When the flamboyant General John Magruder was reassigned to

Texas, he set out denying the lighthouses in that state to the Union.

Attempts were made to blow up six of them, with mixed success. In Texas, the

original Bolivar Point Lighthouse was disassembled for its iron.

A new iron lighthouse was built after the war and it withstood

the devastating Galveston Hurricane of 1905.

When the flamboyant General John Magruder was reassigned to

Texas, he set out denying the lighthouses in that state to the Union.

Attempts were made to blow up six of them, with mixed success.

During and after the war, Lighthouse Board worked hard to restore

lighthouses. At times, they

struggled to get sufficient funding from Congress for the work, but - in

the words of Chairman Shubrick - the Board "endeavored to make [funding]

go as far as possible."

During the war, any recaptured light that could be safely restored was.

Afterwards they began to prioritize those lights most important

to commerce. By May 1866 - a

year after the war ended - they had managed to get 69 of 164 disabled

light stations back in service.

All light stations in Florida were restored by 1872; the last

restored light station in the entire south was probably Hunting Island,

South Carolina where a new tower was finished in 1875 (still standing

today).

Talented Army engineers continued to worth on lighthouses after the war

and some were Union veterans.

Charles Henry Davis is best remembered for winning the Naval

Battle of Memphis, but after that he served for several years on the

Lighthouse Board and as Chief of the Bureau of Navigation.

James C. Duane was the Army of the Potomac's Chief Engineer

during the last year of the war and subsequently served several decades

as a Lighthouse District Engineer in New England.

Orville Babcock served on U. S. Grant's staff, as his postwar

Chief of Staff, and as personal secretary to President Grant.

When Grant left office, Babcock resumed engineering work and

designed the Ponce Inlet Lighthouse near Daytona Beach.

Tragically, he drowned when a boat bringing him ashore to

supervise construction overturned.

Orlando M. Poe was Sherman's Chief Engineer during 1864 and 1865.

After the war, he served as the Lighthouse Board Engineer

Secretary and as District Engineer in the Great Lakes.

He designed the Spectacle Reef Lighthouse in the Straits of

Mackinac and created another lighthouse design used for 8 different

Great Lakes Lighthouses in the 1870s.

The Civil War had a great impact on lighthouses, from the men who

designed, repaired, and rebuilt them to the Union and Confederate

veterans who served as post-war lighthouse keepers.

They were crucial for the Union Navy's blockade and their

restoration was an important wartime and postwar object, for which

hundreds of thousands of dollars (the equivalent of over $10 million

today) were spent over the course of a decade to repair.

Light stations were the site of military activity, including

forts and sometimes battles.

For more about

lighthouses including their role in the Civil War:

Brilliant Beacons by Eric Jay Dolin

A

Short Bright Flash: Augustin Fresnel and the Birth of the Modern

Lighthouse by Theresa Levitt

Florida's Lighthouses in the Civil War by Neil Hurley

The

Lost Light

by Kevin Duffus

A

Light in The Wilderness by James Snyder

Orlando M. Poe: Civil War General and

Great Lakes Engineer by Paul Taylor

When the Southern Lights Went Dark: The Lighthouse

Establishment During The Civil War by Mary Louise

Clifford (a work in process)

Last changed: 07/19/17

Home

About News

Newsletters

Calendar

Memories

Links Join

|