Volume 30, No. 9 – September 2017

Website:

www.CivilWarRoundTablePalmBeach.org

President’s Message:

The Round Table has lost a long-time member, Monroe Ackerman. He passed

away on August 15th.

Monroe gave many presentations, and faithfully made the coffee

for our meetings. His presence will be sorely missed.

In October, William McEachern will present a program entitled:

The Break Through: The Fall of the Confederacy.

At the November meeting, Robert Krasner will speak about Rutherford B.

Hayes. He was a member of

the 23rd

Ohio regiment, lawyer, politician, philanthropist, president of the

National Prison Association, and father of eight.

Robert Macomber will be the Speaker in December.

Gerridine LaRovere

September 13, 2017 Program:

September will be the 30th

anniversary of the Round Table. We will celebrate with festivities

including a special raffle with a $30.00 gift card to Publix.

Our program will be fun and fascinating facts about the Civil War

that you might be surprised to learn.

August 9, 2017 Program:

Our

speaker was

LTC (Ret.) Harold Knudsen.

The presentation drew from his book,

General James Longstreet the

Confederacy’s Most Modern General.

His writings come from his love of military history married up

with his experience with 20th Century Army doctrine, field training,

staff planning, command, and combat experience. Our

speaker was

LTC (Ret.) Harold Knudsen.

The presentation drew from his book,

General James Longstreet the

Confederacy’s Most Modern General.

His writings come from his love of military history married up

with his experience with 20th Century Army doctrine, field training,

staff planning, command, and combat experience.

The South, on the

heels of two major losses at Gettysburg and Vicksburg was facing the

path to defeat if military fortunes could not be turned around in their

favor. General James

Longstreet, Robert E. Lee’s famed War Horse, had prior to the Gettysburg

Campaign, advocated addressing matters around Vicksburg, Mississippi as

a matter of strategic imperative.

He warned Lee that undertaking a strategic offensive into

Pennsylvania was not the correct priority.

Lee overruled him, and they went forward to meet failure at

Gettysburg. Lee then

realized his War Horse had been correct, and subsequently supported

Longstreet’s suggestion to reinforce Braxton Bragg in Georgia and

attempt to wrest the strategic initiative in that theater in the fall of

1863. Longstreet went west

with his corps, and won a stunning victory for Bragg at Chickamauga,

which swung the initiative to Bragg; generating many operational

opportunities that indeed promised to give the strategic initiative to

Bragg’s theater if he acted.

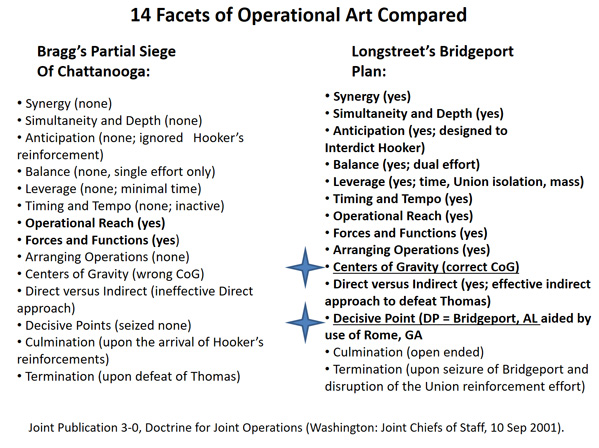

Bragg did not recognize his opportunities.

He decided upon a useless partial siege that eventually lost the

initiative. This allowed the

Union to reinforce Chattanooga, overmatch him, and retake the offensive.

Realistically, it was the Confederacy’s last chance to prevent

defeat.

Most interpretations

of the 1863 Chattanooga campaign claim the unchallenged establishment of

the supply line known as the “Cracker Line” was the decisive event that

caused the reversal of the initiative away from the Confederates and

gave it to the Union. It has

appeared so to many historians, but a defeat like Bragg’s is seldom the

result of a singular tactical event.

The painting of the Cracker Line in this campaign as the turning

point is probably due the tangible effects of lifting the hungry troop’s

morale by restoring full rations covered by the period newspapers and

recent historians, but the truth is, the Cracker Line was a temporary

logistical remedy. (The pontoon bridge established to accommodate the

first wagon loads brought through by Hooker, washed away shortly after

its first uses.) Actually,

steamers (with greater capacity than wagons) shuttling supplies between

Bridgeport and Chattanooga ensured the flow of full rations into

November. Also

contrary to many popular portrayals, General Longstreet not moving

troops into Lookout Valley and the restoration of full rations to

Thomas’ army did not cause the loss of the campaign for Bragg. (The

notion that the Confederates could have denied Union entrance into

Lookout Valley by emplacing troops in this terrain compartment is a

myth; as there were no less than ten ferries and fords where the Union

could cross between Caperton’s Ferry and Kelley’s Ferry.

Covering every one of these and not be flanked, attacked from the

rear, or cut off from Bragg’s main force on Missionary Ridge was

impossible.) The campaign

was largely lost before the Cracker Line was put in, and the true reason

for the Union success is found in the level of war between tactics and

strategy – Operational Art.

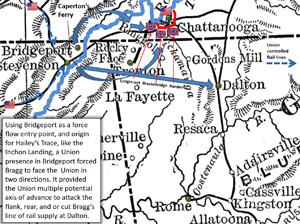

Through the prism of

Operational Art (initially an Industrial Age concept) Longstreet saw the

Union corps movements going on around Bragg were the decisive factors.

Tactical events in Lookout Valley, such as the Union bridgehead

at Brown’s Ferry, the night battle at Wauhatchie, the Cracker Line, and

Bragg’s idea to cut it with a division (or more), were irrelevant.

The key operational facet working against Bragg: the growing

Union Center of Gravity (CoG).

CoG is the key

aspect, that “thing” for simplicity sake, which gives an army its real

power. The CoG of the Union

Army in the Chattanooga campaign was the aggregate strength of all the

reinforcements brought into the area, plus the troops inside

Chattanooga, and also the troops in Knoxville, which all came under

Grants operational control.

While the logistics flow over Hailey’s Trace into Chattanooga was the

lifeline to Thomas, Bragg never made a serious attempt to cut it.

It is also a fact that supply throughput over Haley’s Trace was

sufficient to meet basic needs for the length of time the Union needed

to reinforce. Yet, Bragg

incorrectly thought Haley’s Trace was insufficient, so when the Cracker

Line was put in, he incorrectly identified it as the new CoG by

extension of his myopic tactical focus (even after Hooker linked up with

Thomas). And, as this

campaign illustrates, if one does not correctly figure out his

opponent’s CoG, then the planning and executing of operations that do

not solve the operational problem set will occur.

The opponent will gain the upper hand, and thus tactical actions,

even some successful ones, will not generate the right effects in the

operational realm.

Union CoG within the

Theater = Thomas + Hooker + Sherman + Burnside = 100,000 men

Planning irrelevant

tactical operations we see stemming from Bragg’s fixation with Lookout

Valley when Hooker marched into it on the 27th of October, 1863.

Stating the new supply line was “vital; it involves the very

existence of the enemy at Chattanooga” i.e. the CoG; Bragg wants James

Longstreet to do something about the alarming presence of a new Union

corps operating on his left flank.

Longstreet, however, understood the concepts that would embody

the level of war known in the latter 20th Century as Operational Art.

This type of intuition allowed him to see that the CoG was the

Union corps sized elements that were in the process of gathering.

The Union had already harnessed the key Decisive Point,

which was Bridgeport, Alabama.

Through an unchallenged reinforcement flow into Bridgeport, they

were building a position of dominance in the operational area.

Once Hooker became active, Longstreet knew they were in trouble,

and a major decision to change course was needed by Bragg.

But Longstreet is essentially forced by Bragg (who was in an

agitated state) to attempt a useless tactical action to satisfy Bragg’s

want of “doing something about it.”

They decide on a small scale night attack into Lookout Valley; an

irrelevant and indecisive spasm, which Longstreet planned against the

Union supply train parked in Wauhatchie.

This fails, due to several errors in coordination and other

misunderstandings, to put it mildly, but even if this raid had been

successful, the reality is that it would have had no effect upon the

Union CoG.

Next, Bragg has the idea to have Longstreet move troops into

Lookout Valley, but without any clear offensive objective.

Such a move could only be temporary.

If the Confederates committed large numbers of troops in Lookout

Valley, they would risk this force being cut off in the valley by a

Union thrust south of Lookout Mountain once Sherman joined Hooker.

Longstreet correctly did not follow Bragg’s idea of a blocking

position as it was not tactically sound or part of a clearer purpose.

Ordering a major operation such the one required was the job of

the commanding general, not a corps commander.

It was up to Bragg to decide upon a thorough course of action,

resource that course of action, and issue orders to all his corps

commanders to execute it. As

it were, most interpretations say that Bragg told Longstreet to use all

force necessary to redress the situation; which meant nothing.

Bragg never issued orders for the other two corps commanders to

place their divisions under Longstreet’s control, -- and corps

commanders don’t tell other corps commanders to simply

hand over troops.

Unless Bragg was going to the majority of his divisions in a

decisive strike against Bridgeport, neutralize or push Hooker away,

merely blocking the Cracker Line would not affect the growing Union CoG.

One point that makes

spreading forces for a tactical defense in Lookout Valley a poor choice

was the illusion of the hoped for Union starvation.

Bragg thought from the beginning of his partial siege, he could

cause starvation to collapse the Union hold on Chattanooga. Even though

Union soldiers in Chattanooga were for weeks on half rations (even

quarter rations some days) because of difficulties on the sixty-mile

long Haley’s Trace, they

were not starving. While

they were hungry, no Union soldiers were going to actually starve before

the initiative changed – even without the Cracker Line.

This is the essence of Bragg’s misidentification of the Union

CoG. Although little is

mentioned in the historiography, with the rising water level on the

Tennessee River (allowing some boats to clear the half dozen

obstructions along the way), the Union had steamer traffic between

Bridgeport and Chattanooga beginning early-mid November.

As a result Grant had two multi-modal supply routes running

concurrently into and around Chattanooga by mid-November.

Longstreet sums up the greatest logistical factor for the Union

is that: "they supplied that army for six weeks without the Cracker Line."

The

event that changed the initiative to the Union was the unopposed Union

force flow into Bridgeport of forces under Hooker and Sherman.

The arrival of Joseph Hooker’s corps size element changed the

operational situation to the Confederates having to face the Union in

two directions (they had to face Thomas and now Hooker.)

Sherman’s arrival in November would bring Union operational

domination. This force flow

of reinforcements is the reason that also illustrates why the Cracker

Line was not the Decisive Point.

The Decisive Point of Bridgeport enabled Hooker to arrive and

operate on Bragg’s left/rear, Sherman to arrive and get into place; it

was the origin of Haley’s Trace, and the origin of steamer supply to

Chattanooga. The

event that changed the initiative to the Union was the unopposed Union

force flow into Bridgeport of forces under Hooker and Sherman.

The arrival of Joseph Hooker’s corps size element changed the

operational situation to the Confederates having to face the Union in

two directions (they had to face Thomas and now Hooker.)

Sherman’s arrival in November would bring Union operational

domination. This force flow

of reinforcements is the reason that also illustrates why the Cracker

Line was not the Decisive Point.

The Decisive Point of Bridgeport enabled Hooker to arrive and

operate on Bragg’s left/rear, Sherman to arrive and get into place; it

was the origin of Haley’s Trace, and the origin of steamer supply to

Chattanooga.

If you lose momentum,

you lose the initiative.

Bragg allowed this to occur with his partial siege.

Even though he had some time after the arrival of the first Union

units in Bridgeport on the 25th of September, he never acted against

Bridgeport, losing an opportunity to keep the initiative and further

isolate Thomas at Chattanooga.

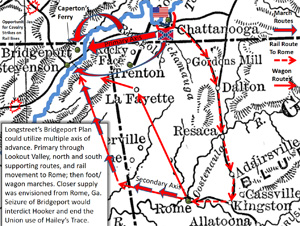

After Longstreet had sent his artillery coordinator, Porter

Alexander to recon the area, and then envisioned an operational level

strike against Bridgeport to achieve precisely these effects, Longstreet

presented this plan to Bragg (as well as President Davis).

Davis told Bragg to execute it, but Bragg would not; his

continued inaction further contributed his defeat.

Grant’s superior numbers and taking the initiative with many of

the facets of Operational Art working in his favor by November allowed

him the freedom to execute operational maneuver against Bragg’s army.

Many like to

speculate the “what if” had Bragg kept Longstreet, and not detached him

to go after Knoxville.

Ostensibly, would Bragg have been stronger and better able to face Grant

in a defensive battle on Missionary Ridge?

Perhaps, and although Grant decided upon a double envelopment of

Bragg’s position on Missionary Ridge the 23rd of November, 1863, it is

worth mentioning he had many options to exercise against Bragg.

Certainly, the “unexpected” frontal assault by Thomas straight up

the ridge into Bragg’s center was a surprise success.

Perhaps if Thomas had attacked Longstreet’s two crack divisions

positioned atop Missionary Ridge (Longstreet’s troops had good

experience setting up a kill zone such as the one they created at

Fredericksburg), Thomas might have suffered a costly repulse.

Still, if Grant’s attacks had failed, and Missionary Ridge proved

too tough a position to take with the plan he started with, the battle

was not over. Grant could

use his superior numbers to both fix Bragg and maneuver around to cut

Bragg’s rail line of supply, forcing him off the ridge that way, for

example. Grant never gave up

after one course of action proved ineffective, he consistently tried

something different. From an

operational planning standpoint, Grant had set the conditions to

dominate once he had overmatched Bragg.

The added bonus of Bragg’s unwise choice to spread out his

forces, sending Longstreet to Knoxville, and another 11,000 troops

halfway between, only made his victory more overwhelming.

The myth that the Chattanooga campaign was lost in Lookout

Valley in the tactical level from the establishment of a supply line is

incorrect. The operational

level corps movements decided this campaign.

Earlier, Bragg had recognized an operational opportunity that the

spread out Union corps prior to Chickamauga presented; and he correctly

chose to strike them under those circumstances.

During Chattanooga, however, he

was not attuned to

the facets of the operational level, and he subsequently lost several

opportunities during this campaign.

Although operational

concepts can be found in earlier wars, they were generally aligned with

the strategic level of war.

Earlier examples, such as the 1781 Yorktown campaign, contained many of

the operational facets.

(There was no professional military education that taught officers to

distinguish a level of war between tactics and strategy.)

However, the synchronization of the land and sea forces and

functions was done in slow motion compared to how quickly a corps

(larger in 1863 than entire armies in the Revolutionary War) could move

in 1863. The concepts that

comprise modern Operational Art became more distinguishable with the

advances of rail, allowing large corps to move great distances quickly,

and as the telegraph allowed coordination of the movements.

At Chattanooga Bragg stuck to the tactical; unable to intuitively

change dimensions, and thus he misidentified the Union CoG.

James

Longstreet recognized the CoG clearly in this campaign.

His professional experiences and the culture of how he and Lee

reviewed their operations brought Longstreet to the necessary level and

ability where he could intuitively determine a course of action to

counter the Union CoG. From

this he envisioned a strike against Bridgeport, Alabama designed to

restore maneuver for the Confederates, eliminate the primary Union force

flow entry point, and keep apart the Union Corp’s so that they could not

support and cooperate with each other.

By overlaying Longstreet’s operational thinking, it becomes clear

that the myths of tactical actions in Lookout Valley and conclusions

about the Cracker Line as the decisive events miss the mark.

Lee’s Warhorse had it right: Bridgeport, not Lookout Valley was

the key to Chattanooga. James

Longstreet recognized the CoG clearly in this campaign.

His professional experiences and the culture of how he and Lee

reviewed their operations brought Longstreet to the necessary level and

ability where he could intuitively determine a course of action to

counter the Union CoG. From

this he envisioned a strike against Bridgeport, Alabama designed to

restore maneuver for the Confederates, eliminate the primary Union force

flow entry point, and keep apart the Union Corp’s so that they could not

support and cooperate with each other.

By overlaying Longstreet’s operational thinking, it becomes clear

that the myths of tactical actions in Lookout Valley and conclusions

about the Cracker Line as the decisive events miss the mark.

Lee’s Warhorse had it right: Bridgeport, not Lookout Valley was

the key to Chattanooga.

[Editor’s note:

At this point, LTC Knudsen’s materials, which he sent by e.mail

ends. His talk, however,

went on. The next remarks

are from my memory of what he said.]

Knudsen introduced

our group to the modern day concept of Operational Art, the level of war

that interrelates tactics and strategy.

Before the advent of

highspeed logistics, the commanders handled strategy

and the officers in the field translated this into tactics.

As the above story demonstrates, Longstreet saw that the

strategic plan to eliminate the Union army in Tennessee could not be

done by tactics alone as Bragg had tried.

Longstreet’s vision of the CoG saw the need to eliminate the

source of supply from Bridgeport indirectly, by seizing a Decisive

Point. This was far short of

a strategy, but far more than a series of tactical maneuvers and/or

battles. Bragg never got it.

The presentation

illuminated this with illustrations from the long past and more recent

past. One illustration was

General Douglas MacArthur and the Inchon landing.

The strategy was to push Chinese and North Koreans out of the

Pusan Perimeter. MacArthur

reasoned that tactics like Bragg used to punch at Thomas would not work.

He used operational art to land at the “unlandable” port of

Inchon and push across the narrow peninsular to cut off the north’s

supplies and possibly encircle the enemy.

The tactics at Inchon involved the capture of an airfield, the

destruction by air power of a massed tank counter stroke, and the

liberation of Seoul. I would

argue that Longstreet and MacArthur both had the 14 points listed below

well in hand.

Last changed: 08/22/17

Home

About News

Newsletters

Calendar

Memories

Links Join

|