The President’s Message:

I am so pleased to announce that the Civil

War Round Table of the Palm Beaches has a new location for our meetings.

Harold Teltser has worked very

hard to secure a wonderful new meeting place.

His efforts are greatly are

appreciated.

Starting Wednesday, October 10th

at 7:00 PM the Round Table will meet at the Atlantis Council Chambers,

160 Orange Tree Drive, Atlantis 33462.

Directions from I-95 and Lantana Road:

1.

Exit on Lantana Road and go west on Lantana Road for 1.5 miles.

2.

Turn right onto South Congress Avenue 0.4 mile.

3.

Turn left onto Clubhouse Blvd. 0.3 mile.

4.

There is a guardhouse. However,

you do not need to show identification. Simply wave and the guard

will open the gate. If you do need further directions for the Council

Chamber, please ask the guard.

5.

Turn right on Orange Tree Drive. Destination is the white building

immediately on corner. Pull into parking lot.

Directions from US441 and Lantana Road:

1.

Go east on Lantana Road 6.9 miles.

2.

Turn left onto South Congress Avenue 0.4 mile

3.

Turn left onto Clubhouse Blvd. 0.3 mile.

4.

There is a guardhouse. However,

you do not need to show identification. Simply wave and the guard

will open the gate. If you do need further directions for the Council

Chamber, please ask the guard.

5.

Turn right on Orange Tree Drive. Destination is the white building

immediately on corner. Pull into parking lot.

October 10, 2018 Program:

Is the name Mudd still a dirty word? Janell

Bloodworth will talk about Dr. Samuel A. Mudd.

The second half of the program Gerridine LaRovere will discuss

Anna Elizabeth Dickinson, the highest paid female orator on the

political circuit. Her spoken

words assured a Republican victory in Connecticut in 1863.

August 8, 2018 Program:

Marshall Krolick gave us a presentation titled

The Boy Generals: The Promotion of Custer, Merritt, and Farnsworth.

During the early morning hours of June 28, 1863 Joseph Hooker was

relieved as commander of the Army of the Potomac and George Gordon Meade

was appointed to replace him. This occurred while the army was at

Fredericksburg, Maryland during a critical stage in the campaign which

would culminate at Gettysburg. Less

than twelve hours later, also on June 28, 1863, Meade sent the following

telegram to General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck:

"To

June 28, 1963

Halleck, Major General

To organize with efficiency the cavalry force now with this army, I

require three Brigadier Generals. General Pleasonton nominates Captain

Farnsworth, 8th Illinois Cavalry, Captain (sic) George A. Custer, 5th

U.S. Cavalry, Captain Wesley Merritt, 2nd U.S. Cavalry. Can these

officers be appointed?

Meade

Major General Commanding"

Without waiting for a response, Meade issued the following order on that

same day:

"SPECIAL ORDERS,) HEADQUARTERS ARMY OF THE POTOMAC,

No. 175. )

Frederick, MD., June 28, 1863

The following-named general officers are assigned to duty with the

Cavalry Corps, and will report to Major-General Pleasonton:

Brigadier-General Farnsworth, U.S. Volunteers; Brig. Gen. George A.

Custer, U.S. Volunteers; Brig. Gen. Wesley Merritt, U.S. Volunteers………

By command of Major-General Meade:

S. WILLIAMS,

Assistant Adjutant-General."

In fact, the Commissions sought were granted on June 29, 1863.

So the lives and fates of three young officers, two captains and a first

lieutenant, were unalterably changed by one of the most unusual

promotions in the history of the United States Army. These promotions

can be readily understood if they had been made for cause, such as for

great deeds, for battlefield bravery, for exhibited qualities of

leadership, or for brilliant strategic and tactical ability. To

determine if that was the case here, the lives and careers of the

promoted officers up to June, 1863 must be examined.

Captain

Wesley Merritt was born on June 16, 1836 in New York City, but spent

most of his early life in Illinois. Appointed to West Point, he

graduated twenty-second out of forty-one in the class of 1860 and was

commissioned a lieutenant in the 2nd Dragoons. Subsequently, Merritt

served in Utah where one of his superiors was then Captain Alfred

Pleasonton. After the outbreak of the Civil War, he marched back east

with his regiment and, by February of 1862, Merritt was serving as

aide-de-camp to Philip St. George Cooke, the commander of the Federal

cavalry during the Peninsula Campaign. For the balance of that year he

served as a staff officer in the Washington defenses. In the Spring of

1863, just prior to the Chancellorsville Campaign, he became an

aide-de-camp to George Stoneman. At one point during the fiasco that has

come to be known as Stoneman's Raid, Merritt commanded a detachment

which was successful in burning bridges over the South Anna River and

destroying railroad facilities. In late May, he renewed his relationship

with Alfred Pleasonton by becoming an aide-de-camp on the latter's

staff. However, early June found Merritt back with his old regiment, now

known as the 2nd U.S. Cavalry, which he commanded at the Battle of

Brandy Station. A contemporary described Merritt at this time as

reticent, almost shy, but an old army type in that he was a tough

disciplinarian, almost a martinet. Captain

Wesley Merritt was born on June 16, 1836 in New York City, but spent

most of his early life in Illinois. Appointed to West Point, he

graduated twenty-second out of forty-one in the class of 1860 and was

commissioned a lieutenant in the 2nd Dragoons. Subsequently, Merritt

served in Utah where one of his superiors was then Captain Alfred

Pleasonton. After the outbreak of the Civil War, he marched back east

with his regiment and, by February of 1862, Merritt was serving as

aide-de-camp to Philip St. George Cooke, the commander of the Federal

cavalry during the Peninsula Campaign. For the balance of that year he

served as a staff officer in the Washington defenses. In the Spring of

1863, just prior to the Chancellorsville Campaign, he became an

aide-de-camp to George Stoneman. At one point during the fiasco that has

come to be known as Stoneman's Raid, Merritt commanded a detachment

which was successful in burning bridges over the South Anna River and

destroying railroad facilities. In late May, he renewed his relationship

with Alfred Pleasonton by becoming an aide-de-camp on the latter's

staff. However, early June found Merritt back with his old regiment, now

known as the 2nd U.S. Cavalry, which he commanded at the Battle of

Brandy Station. A contemporary described Merritt at this time as

reticent, almost shy, but an old army type in that he was a tough

disciplinarian, almost a martinet.

Capt.

Elon J. Farnsworth was born July 30, 1837 in Green Oak, Michigan. His

early life was spent in Michigan and then in Rockton, Illinois. In 1855

Farnsworth enrolled at the University of Michigan, but in 1858 he and

several others were expelled for what was described as a "drunken

escapade". Almost immediately he joined Albert Sidney Johnston's Mormon

Campaign as a civilian forage master. After the Civil War began, he

returned to Illinois to become a first lieutenant and adjutant in the

8th Illinois Cavalry, a regiment raised in the summer of 1861 by his

uncle, John Farnsworth, a former Republican congressman. In December he

was promoted to captain of Company K. Mule the regiment was quartered in

Alexandria, Virginia in the winter of 1861-1862 Elon is reported to have

physically pulled from the pulpit an Episcopal rector who had omitted

from his service the normal prayer for the President of the United

States. In the spring of 1863, Farnsworth joined the staff of Alfred

Pleasonton. A description of Elon Farnsworth at this time by James Kidd,

future colonel of the 6th Michigan Cavalry, pictured him as proud,

ambitious and fiery, yet poised and discreet, a man true as steel to his

country and to his convictions of duty and manhood. Capt.

Elon J. Farnsworth was born July 30, 1837 in Green Oak, Michigan. His

early life was spent in Michigan and then in Rockton, Illinois. In 1855

Farnsworth enrolled at the University of Michigan, but in 1858 he and

several others were expelled for what was described as a "drunken

escapade". Almost immediately he joined Albert Sidney Johnston's Mormon

Campaign as a civilian forage master. After the Civil War began, he

returned to Illinois to become a first lieutenant and adjutant in the

8th Illinois Cavalry, a regiment raised in the summer of 1861 by his

uncle, John Farnsworth, a former Republican congressman. In December he

was promoted to captain of Company K. Mule the regiment was quartered in

Alexandria, Virginia in the winter of 1861-1862 Elon is reported to have

physically pulled from the pulpit an Episcopal rector who had omitted

from his service the normal prayer for the President of the United

States. In the spring of 1863, Farnsworth joined the staff of Alfred

Pleasonton. A description of Elon Farnsworth at this time by James Kidd,

future colonel of the 6th Michigan Cavalry, pictured him as proud,

ambitious and fiery, yet poised and discreet, a man true as steel to his

country and to his convictions of duty and manhood.

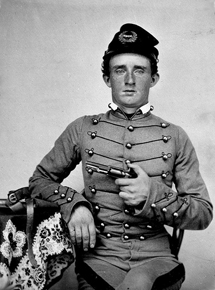

First

Lieutenant George Armstrong Custer was born on December 5, 1839 in Ohio

and spent his early years in Monroe, Michigan. At West Point he was

ranked last in the class of 1861, a standing achieved partly because of

the excessive time he spent under detention because of rules violations.

His first assignments during the Civil War were as an aide on the staffs

of Winfield Scott and George B. McClellan. By May 15, 1863 he had been

appointed to the staff of Alfred Pleasonton, the new commander of the

cavalry corps of the Army of the Potomac. In this capacity he rode with

John Buford at the Battle of Brandy Station and there helped to rally

the brigade of Grimes Davis after the latter's death early in the

battle. A description of Custer is certainly unnecessary, but among the

words which come automatically to mind are impetuous, flamboyant, brave,

and vain. First

Lieutenant George Armstrong Custer was born on December 5, 1839 in Ohio

and spent his early years in Monroe, Michigan. At West Point he was

ranked last in the class of 1861, a standing achieved partly because of

the excessive time he spent under detention because of rules violations.

His first assignments during the Civil War were as an aide on the staffs

of Winfield Scott and George B. McClellan. By May 15, 1863 he had been

appointed to the staff of Alfred Pleasonton, the new commander of the

cavalry corps of the Army of the Potomac. In this capacity he rode with

John Buford at the Battle of Brandy Station and there helped to rally

the brigade of Grimes Davis after the latter's death early in the

battle. A description of Custer is certainly unnecessary, but among the

words which come automatically to mind are impetuous, flamboyant, brave,

and vain.

Thus, as the armies rested after Chancellorsville, an evaluation of

Merritt, Farnsworth and Custer would cite to jobs well done, but

certainly not to careers of great distinction. Their performance, while

commendable, was not any different from that of hundreds of other

officers. In fact, such veteran colonels of the Cavalry Corps of the

Army of the Potomac as John McIntoch, William Gamble, George Chapman,

Henry Davies and others could certainly expect promotion before junior

grade staff and line officers. Yet, on June 28, 1863 these three young

men were jumped from captain and first lieutenant to brigadier general

and thus the obvious question is "why?" The answer clearly was not based

on accomplishment or proven ability. That fact was confirmed by Custer

himself. In a confidential letter written July 26, 1863 to his close

friend and patron, Judge Christiancy of Monroe, Michigan, Custer

expressed surprise.

Rather, the reasons for these unprecedented promotions are to be found

in the deeds and minds of others, as a result of ambition, desire for

power, bigotry and political intrigue. In fact, the three promoted

officers were but pawns in a much larger game. To examine those

circumstances two other individuals must be introduced to the cast of

characters.

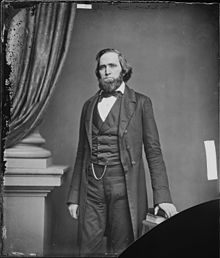

The

first is John Farnsworth, uncle of Elon. Born in Quebec, Canada on March

27, 1820, he spent his early life in Ann Arbor, Michigan as a surveyor.

In 1842 he relocated to St. Charles, Illinois and opened a law practice.

Ten years later, in 1852, he moved his office to Chicago where he became

a friend of Abraham Lincoln and quickly established a reputation as a

virulent Lovejoy abolitionist. On that platform, and as a Republican, he

was elected to Congress from Chicago in 1856 and again in 1858. However,

by 1860 the political climate had moderated in his district as people of

reason sought a less strident representative in an effort to avoid war.

Thus John Farnsworth was defeated that year for renomination and he

returned to his law practice in Chicago. The

first is John Farnsworth, uncle of Elon. Born in Quebec, Canada on March

27, 1820, he spent his early life in Ann Arbor, Michigan as a surveyor.

In 1842 he relocated to St. Charles, Illinois and opened a law practice.

Ten years later, in 1852, he moved his office to Chicago where he became

a friend of Abraham Lincoln and quickly established a reputation as a

virulent Lovejoy abolitionist. On that platform, and as a Republican, he

was elected to Congress from Chicago in 1856 and again in 1858. However,

by 1860 the political climate had moderated in his district as people of

reason sought a less strident representative in an effort to avoid war.

Thus John Farnsworth was defeated that year for renomination and he

returned to his law practice in Chicago.

As did many politicians and men of prominence during the summer of 1861,

in response to President Lincoln's call for troops John Farnsworth

raised a regiment, the 8th Illinois Cavalry. He became its colonel and

his nephew Elon was appointed a lieutenant. When the regiment moved to

Washington in September, 1861, it was personally reviewed by the

President, who referred to it as "Farnsworth's big abolition regiment".

During the first year of the war, the 8th Illinois and its colonel

performed adequately, if unspectacularly. However, by Antietam Uncle

John was in command of a cavalry brigade in the division led by Alfred

Pleasonton. On November 29, 1862, John Farnsworth was commissioned a

brigadier general of volunteers, but that same month he had been

re-elected to Congress. On April 4, 1863 he took his seat, resigning his

army commission that same day. The fifth and final piece of the puzzle

is in fact the prime mover of the entire scenario. He is a man whose

name has already been associated with each of the other members of our

cast of characters. That man, referred to by historian Edward Long acre

as "The Knight of Romance" is, of course, Alfred Pleasonton. He was born

in Washington, D.C. on July 7, 1824 and graduated from West Point in

1844, ranking seventh out of twenty-five. He saw service in the Mexican

War, on the frontier, and in the campaign against the Seminoles. By

1860, Pleasonton was a captain in the 2nd United States Dragoons,

serving in Utah where Wesley Merritt was a lieutenant and Elon

Farnsworth was a civilian forage master. In the fall of 1861 he was

ordered to march the regiment back to Washington and he served with it

that winter in the Washington defenses. Promoted to major on February

15, 1862, he saw action during the Peninsula Campaign. On July 16, 1862,

Pleasonton was appointed a brigadier general of volunteers and during

the Antietam and Chancellorsville Campaigns he commanded a cavalry

division. At Antietam one of his brigades was led by John Farnsworth. In

early June, 1863, Pleasonton replaced George Stoneman as commander of

the cavalry corps of the Army of the Potomac and was in command of all

Federal troops on the field at the Battle of Brandy Station on June 9th.

Descriptions

of Alfred Pleasonton in the writings of his contemporaries often include

such favorable terms as professionally competent, self-confident, and an

able strategist and battlefield tactician. However, these are more than

offset by the negative references, which include ambitious, desirous of

power, vain, swaggering, overly concerned with his reputation and, most

damning of all, an unprincipled liar, as witness his report of Brandy

Station. In dress, he was a dandy, affecting fancy uniforms, a jaunty

mustache, gauntlets, and a riding whip. To complete the picture, his

relationship with the three young officers must be reviewed. At least

two, his then current staff officers, Custer and Elon Farnsworth,

regarded Pleasonton as a father figure, even to emulating his manner of

dress. Descriptions

of Alfred Pleasonton in the writings of his contemporaries often include

such favorable terms as professionally competent, self-confident, and an

able strategist and battlefield tactician. However, these are more than

offset by the negative references, which include ambitious, desirous of

power, vain, swaggering, overly concerned with his reputation and, most

damning of all, an unprincipled liar, as witness his report of Brandy

Station. In dress, he was a dandy, affecting fancy uniforms, a jaunty

mustache, gauntlets, and a riding whip. To complete the picture, his

relationship with the three young officers must be reviewed. At least

two, his then current staff officers, Custer and Elon Farnsworth,

regarded Pleasonton as a father figure, even to emulating his manner of

dress.

That Custer returned this affection is evidenced by his gift to Alfred

Pleasonton, in the spring of 1863, of a magnificent horse captured from

a Confederate officer. As for Wesley Merritt, he had served directly

under Pleasonton several times, including a short stint as aide-de-camp.

Both Custer and Merritt had been previously recommended for promotion by

Pleasonton. Last, but certainly not least, Elon Farnsworth was John

Farnsworth's nephew and by June, 1863 John Farnsworth had become a most

important man in Alfred Pleasonton's life. It was through the elder

Farnsworth that Pleasonton hoped to accomplish what he wanted most in

life at this time. These goals were: (1) promotion to major general; (2)

an increase in the size of the Cavalry Corps, thereby making his command

more important; (3) the appointment of subordinate commanders personally

loyal to him so as to solidify his power base; and (4) elimination of

foreigners from his command.

The last of these desires resulted from the fact that Alfred Pleasonton

was a bigot, prejudiced against anyone not a native born American. He

regarded all foreigners as inept mercenaries. To illustrate this, among

his writings of this period can be found statements such as "In every

instance foreigners have injured our cause". When Alfred Pleasonton

assumed command of the Cavalry Corps, Europeans such as Sir Percy

Wyndham, Luigi Di Cesnola and Alfred Duffie held important commands. In

every instance, by the end of the Gettysburg campaign they were gone. In

several cases these removals were for unjust cause fostered by

Pleasonton.

However, in June of 1863, those gentlemen were not Pleasonton's prime

target among the foreign born. That distinction belonged to an

unfortunate Hungarian, Brigadier General Julius Stahel. This poor soul

not only was a foreigner, but had the misfortune to be in command of a

cavalry division, containing thirty-six hundred troopers, attached to

the defenses of Washington. Alfred Pleasonton not only instinctively

disliked Stahel because of the latter's foreign birth, but he also

coveted Stahel's division as an addition to his cavalry corps. Thus

communiques began to descend on Washington from Pleasonton's

headquarters criticizing Stahel's performance and cooperation, although

in fact at this time Stahel's troopers were providing better

intelligence of Confederate movements than was Pleasonton.

To support his desire to populate the command structure of the cavalry

corps with his own people, Alfred Pleasonton also resorted in June, 1863

to his always prolific, if not always truthful, pen. For example, his

report of the Battle of Upperville, fought on June 21, stated: "Give me

good commanders and I will give you good results".

However, above all, Alfred Pleasonton was a realist and a veteran

observer of the politics of Washington. He knew letters alone would not

accomplish his four goals. He needed a friend in court, a powerful

political voice with the ear of Lincoln and the Radical Republican

leadership of Congress. Fortunately, Pleasonton knew just where to turn,

to his good friend and former subordinate, the Radical Republican

congressman, the friend of Lincoln, John Farnsworth. Already Pleasonton

had cemented their relationship by appointing Elon Farnsworth to his

staff. In addition, Pleasonton and John Farnsworth had become regular

correspondents since John Farnsworth left the army. Now Alfred

Pleasonton peppered his letters to John Farnsworth with criticisms of

Stahel, suggestions that the latter's division belonged with the Army of

the Potomac, pleas that Pleasonton should be allowed to appoint his own

officers, and queries why he as a corps commander was not a major

general.

The schemes of Alfred Pleasonton reached their

finest hour on June 23, 1863 when he wrote a letter, marked "private",

to John Farnsworth.

It was full of venom directed at

Stahel.

Not content with his own words, Alfred

Pleasonton added the coup-de-gras. Enclosed with the letter to John was

a note from nephew Elon:

"Pleasonton is still not a Major

General. While Pleasonton has fought thru 3 severe battles, all this

time Stahel has four or five thousand cavalry in and about Washington

just doing nothing at all. Trains passing between here and Fairfax C.H.

are burned by Bushwhackers, our dispatches intercepted and yet Stahel

does nothing. Now if you can do anything to get the cavalry consolidated

and Stahel left out, for Gods sake do it. You hardly know or can imagine

the bitter feeling that exists among the officers of the cavalry towards

Stahel and those who are trying to set him and other Dutchmen up, Duffie

has failed on two occasions. The Gen'l. speaks of you can do are

commending me for Brig. I do not know that I ought to mention it for

fear that you will call me an aspiring youth. I am satisfied to serve

through this war in the line in my Reg't as a Capt. or on Gen'l

Pleasonton's staff. But if I can do any good anywhere else of course

'small favors and etc.' now try and talk all this into the President and

do an immense good...

"Since these letters were written

from the area of Aldie, only fifty miles from Washington, it can

certainly be assumed that they reached John Farnsworth by the 25th, if

not on the 24th. In determining the result of this and the other

Pleasonton correspondence, an examination of the events of the next few

days proves very interesting. On June 24, 1863, Alfred Pleasonton was

nominated to the Senate for confirmation as a Major General. On June 28,

Custer, Merritt and Farnsworth, Pleasonton's personal choices, were

promoted to brigadier general. On that same day Julius Stahel was

relieved from the command of his division. Also on June 28, Stahel's

former division was added to the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the

Potomac, giving Alfred Pleasonton a total force of over twelve thousand

men. Thus, four goals had been set and four goals had been achieved.

The reaction of the three promoted officers was clearly

revealed by how they handled the change of uniform in the midst of a

volatile campaign. Merritt, quiet and understated, simply continued to

wear what he had until he could obtain a proper general's uniform. Elon

Farnsworth, fiery and dashing, borrowed a general's trappings from

Alfred Pleasonton, whose dress he already was copying. And then there

was George A. Custer. It is perhaps best to let Major James Kidd of the

6th Michigan Cavalry describe Custer's self-designed new attire when the

latter arrived to assume his new command:

"my eyes were instantly riveted upon a figure only a few feet distant,

whose appearance amazed if it did not for the moment amuse me. . . He

was clad in a suit of black velvet, elaborately trimmed with gold lace,

which ran down the outer seams of his trousers, and almost covered the

sleeves of his cavalry jacket. The wide collar of a blue navy shirt was

turned down over the collar of his velvet jacket, and a necktie of

brilliant crimson was tied in a graceful knot at the throat, the long

ends falling carelessly in front. The double rows of buttons on his

breast were arranged in groups of twos, indicating the rank of brigadier

general…" It went on from

there. Another contemporary

description, perhaps a touch more critical, stated that Custer's attire

made him look like "a circus rider gone mad." "Three dashing and

brilliant young officers, who have been appointed in violation of red

tape and regardless of political influence because of their rare fitness

to lead cavalry."

In any event, the promotions were made and duly confirmed.

The three officers, regardless of the style of uniform they adopted,

reported to their new commands. For Merritt, it was back to his old

command, as he took over the Reserve Brigade, officially the Third

Brigade of Buford's First Division. This division was assigned to lead

the left front of the Federal advance into Maryland and Pennsylvania.

Stahel's former division was designated as a new Third Division and

divided into two brigades. The first was given to Elon Farnsworth and

the second to George Custer. The latter brigade, consisting of the 1st,

5th, 6th, and 7th Michigan Cavalry regiments, would become famous under

Custer's leadership as the "Michigan Brigade". The new commander of this

third division was Judson Kilpatrick. Rash, foolish and reckless,

without tactical or strategic ability, he would quickly earn his

nickname, "Kill Cavalry". Unfortunately the "cavalry" referred to was

usually his own, not the enemy's.

On July 3rd at Gettysburg, on the eastern edge of the

town, Gregg's Second Division, aided materially by Custer's brigade,

dueled Stuart as the latter attempted to gain the Federal rear. The key

moment in this too often neglected action was the mounted charge of the

1st Michigan, personally led by George Custer, against the advance of

the troops of Wade Hampton and Fitz Lee. This, of course, was the famous

"C'mon you Wolverines" incident and it, and the way Custer handled his

brigade generally, played an important role in Stuart's defeat.

Later that same afternoon, as the remnants of the divisions

of Pickett, Pettigrew and Trimble were streaming back to Seminary Ridge,

another cavalry charge was mounted, this time on the southern edge of

the field and with tragically different results. The idiotic Judson

Kilpatrick had decided that the Army of Northern Virginia was

demoralized after its repulse. Thus he ordered Elon Farnsworth to make a

mounted charge against the Confederate right, the divisions of Hood and

McLaws, posted in the south end of the Devil's Den area, west of Big

Round Top. This was an area of woods, fences, huge boulders, and broken

ground, certainly no place for a cavalry attack. Upon Kilpatrick's

orders for this suicidal charge, a Federal officer heard the following

exchange between Kilpatrick and Elon Farnsworth:

"Farnsworth: "General, do you mean it? Shall I throw my

handful of men over rough ground, through timber, against a brigade of

infantry? The First Brigade has already been fought half to pieces;

these are too good men to kill." Kilpatrick countered with the age-old

charge: "Do you refuse to obey my orders? If you are afraid to lead this

charge I will lead it." "Take that back!", Farnsworth shouted as he rose

in his stirrups, his wrath blazing out of control. As Kilpatrick

apologized the quarrel died down and Farnsworth said: "General, if you

order the charge I will lead it, but you must take the responsibility."

When the attack began, Farnsworth and his men soon found

themselves riding a gauntlet between two Confederate lines. As the

troopers desperately sought an escape route, Elon Farnsworth was killed,

his body pierced by five bullets. The reaction of Alfred Pleasonton when

he heard of Farnsworth's death was to say "Nature made him a general".

One can only wonder at the reaction of John Farnsworth, whose

machinations with Alfred Pleasonton, not nature, had resulted in the

promotion and subsequent death of his nephew.

As for Wesley Merritt, his assigned role on the Army's far

left flank resulted in two other clashes on July 3rd. Badly outnumbered,

one of his regiments, the 6th U.S., fought unsuccessfully at Fairfield

against the cavalry guarding the Confederate trains. Later that day,

just prior to Farnsworth's charge the remainder of Merritt's brigade

battled Confederate infantry in an inconclusive action along the

Emmitsburg Road.

So the Gettysburg Campaign ended and the actors on our stage

went on to play out the roles in life that fate, and Alfred Pleasonton,

had dealt them. For Alfred Pleasonton himself it was not to be a happy

road, certainly not the one he had envisioned. By the spring of 1864,

Meade had had enough of him. Pleasonton's testimony before the Committee

on the Conduct of the War had supported Hooker, Butterfield, and Birney

in their attacks against Meade. Also, Pleasonton's lies were catching up

with him. Thus, when Grant brought Sheridan east with him, Meade was

more than happy to let Alfred Pleasonton go. He was relieved from

command of the Cavalry Corps on March 25, 1864. Banished to Missouri, he

performed extremely well during Price's Raid and the balance of the war,

but it was an arena without an audience. On the reorganization of the

army in 1866 he declined an infantry command. However, his regular army

rank was still only major of the 2nd U.S. Cavalry. Incensed that this

left him subordinate in the regiment to those he had ranked during the

war, he resigned. For thirty years he lived out a lonely life in

Washington, holding minor government jobs for his livelihood. Alfred

Pleasonton died on February 17, 1897. His bitter memories of his career

in the army are best reflected by the fact that no reference to his

military service appears on his tombstone.

As for the three young men whose careers Pleasonton's

ambition had so profoundly affected, Elon Farnsworth of course was dead,

forgotten today except for a restaurant in Gettysburg bearing his name

and a monument over his grave in Rockton, Illinois. Custer's career

needs no retelling here, except to emphasize that in 1864 and 1865 he

performed brilliantly as a cavalry leader. Quiet, unassuming Wesley

Merritt went on to enjoy one of the most distinguished careers in the

history of the United States Army. His regular army promotions included

colonel in 1876, brigadier general in 1887 and major general in 1895.

For a period of time he served as Superintendent of West Point, and

later commanded the forces in Philippines during the Spanish American

War. Retiring in 1900, Merritt died in 1910 and was buried at West

Point, near the grave of Custer.

So as a result of the ambition and conniving of Alfred

Pleasonton, the lives of these three young men touch such diverse places

as the foot of Big Round Top at Gettysburg, the Little Big Horn in

Montana, and Manilla in the Philippines. One can only wonder where Elon

Farnsworth, Wesley Merritt and George Custer would have gone and how

different their lives might have been if they had not been pawns in the

manipulations of Alfred Pleasonton.

Last Changed: 09/26/18

|