The President’s Message:

Please note the change in the Round Table meeting date.

For November only, we will meet on

Wednesday, November 7th

at 7:00 PM.

The Round Table had its first meeting at the Atlantis City

Council Room. There was an

excellent turn out at our new location.

Once again, thank you to Harold Teltser for arranging this lovely

venue.

Dues are due! Please mail a

check or bring your dues to the next meeting.

We would greatly appreciate any extra contribution which helps in

obtaining future speakers.

Mark your calendar. Noted

author and lecturer, Robert Macomber will be our speaker Wednesday,

December 12th.

Gerridine LaRovere

November 7, 2018 Program:

The November program will be “Haunted Battlefields” given by Peppy

Lizza. Learn about the

history of the Cashtown Inn in Gettysburg and the USS Constellation in

Baltimore Harbor as well as their involvement in the paranormal

experiences. Peppy will

briefly discuss other battlefields.

October

10, 2018 Program:

Dr. Samuel Mudd by Janell

Bloodworth

Your name is mud.

This is not a phrase that elicited admiration or any sense of

pleasure. This is especially true for any member, or descendent, of the Mudd family of

Maryland. The expression,

your name is mud, came into being because Dr. Samuel Mudd of Bryantown,

Maryland set an injured man’s broken leg.

This act led to Dr. Mudd’s misfortune of spending almost 4 years

in prison. I’m going to

jump to May 9, 1865. This

is a few weeks after Lincoln was assassinated.

On May 9, 1865, eight prisoners, in chains, flanked by soldiers

of the Veterans Reserve Corps filed slowly into the makeshift courtroom

on the third floor of Washington’s Arsenal Penitentiary.

Nine Army officers set ready to try them for murder.

Among the accused stood the young physician from Bryantown,

Maryland, Dr. Samuel Mudd.

In prison for almost 2 weeks he did not have the benefit of any

attorney. He had possibly,

not yet begun to comprehend the enormity of the depth of the charges

facing him.

especially true for any member, or descendent, of the Mudd family of

Maryland. The expression,

your name is mud, came into being because Dr. Samuel Mudd of Bryantown,

Maryland set an injured man’s broken leg.

This act led to Dr. Mudd’s misfortune of spending almost 4 years

in prison. I’m going to

jump to May 9, 1865. This

is a few weeks after Lincoln was assassinated.

On May 9, 1865, eight prisoners, in chains, flanked by soldiers

of the Veterans Reserve Corps filed slowly into the makeshift courtroom

on the third floor of Washington’s Arsenal Penitentiary.

Nine Army officers set ready to try them for murder.

Among the accused stood the young physician from Bryantown,

Maryland, Dr. Samuel Mudd.

In prison for almost 2 weeks he did not have the benefit of any

attorney. He had possibly,

not yet begun to comprehend the enormity of the depth of the charges

facing him.

Dr. Mudd’s crime was setting an injured man’s leg.

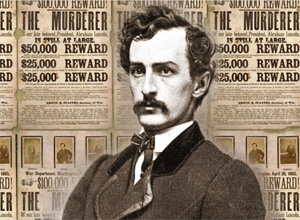

That man was John Wilkes Booth, who had broken his leg while

assassinating President Lincoln.

For his apparently unwilling part in the conspiracy, Mudd was

brought to trial and adjudged guilty.

His sentence was life imprisonment.

He missed death by hanging by the vote of one man.

Four of his fellow prisoners were executed on July 7, 1865.

One of those four was Mary Surratt, the first woman executed by

the federal government.

Mudd initially thought he too would swing from the gallows.

Originally sentenced to the federal penitentiary in Albany, New

York, Mudd was sent instead to Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas.

Fort Jefferson was a maximum-security prison, 60 miles west of

Key West.

Mudd was convicted ostensibly because he had met the assassin Booth at

least once prior to the murder.

Some think it would be more correct to believe that he was

condemned by Gen. Lew Wallace, who reportedly said: “The deed is done;

somebody must suffer for it, and he may as well suffer as anybody else.”

The chain of events that would catapult 31-year-old Dr. Mudd into prison

for life, began the night of April 14, 1865.

Now we all know about Lincoln’s assassination; however, I have to

go back to some of it to keep in sequence what happens next.

The shattered armies of the Confederacy had begun to dissolve

only five days before. Lee

had surrendered to Grant at Appomattox.

The Civil War seem to be over.

That Friday night, Good Friday, President Lincoln and his wife

visited Ford’s theater in Washington with Maj. Henry Rathbone and his

fiancée Clara Harris. They

went to see a play,

Our American Cousin.

This was the night John Wilkes Booth

had been waiting for. Booth

was a member of a great acting family.

His father, Julius Brutus Booth, had been the most famous actor

of the previous generation.

One of his brothers, Edwin, was the most famous actor of the present

generation. Many think he

was the greatest Shakespearean actor of all times.

Another brother was equally famed.

John Wilkes Booth made a comfortable living, close to $20,000 a

year. Back in the 19th

century that was a heck of a lot of money.something really big, like

pulling down the Colossus of Rhodes.

That would cause his name to be remembered down through the ages.

The Colossus of Rhodes turned out to be Abraham Lincoln.

But the critics of the time would compare him unfavorably to others of

his family. But John was

intent on etching his fame on the pages of history.

Legend has Booth, while still in

school, reporting a boyhood dream of someday doing something really big,

like pulling down the Colossus of Rhodes.

That would cause his name to be remembered down through the ages.

The Colossus of Rhodes turned out to be Abraham Lincoln.

The 26-year-old Booth, an ardent secessionist,

originally planned to kidnap Lincoln.

He would abduct the president from Washington and carry him to

lower Maryland and continue on to Confederate Richmond.

Once captured Lincoln could be ransomed for needed Confederate

cash. But after several

false starts, and postponements, Booth began to turn from thoughts of

abduction to thoughts of assassination.

The assassination proved to be ridiculously easy.

The day he was scheduled to attend the theater Lincoln asked

Secretary of War Stanton for a military guard.

He was refused. Some

later day historians would once point the finger of suspicion at Stanton

as a possible conspirator, for this and other questionable deeds.

So, Lincoln was left unprotected.

Now depending on which book or article you read, he was supposed

to have a police guard there named John Parker.

John Parker was probably there, but he left for a bar nearby and

left Lincoln unprotected.

Midway through the third act John Wilkes Booth, wearing dark clothes and

spurs on his riding boots, walked behind Lincoln and shot him through the head.

Major Rathbone jumped out of his seat and attempted,

unsuccessfully, to grapple with the assailant.

Booth attacked him with a knife and then jumped over the

balustrade catching a spur on the flag adorning the box.

He fell heavily to the stage some 12 feet below.

A bone in his left leg snapped.

Despite his injury, and despite being in pain, Booth hobbled out

a side door and rode off on horseback through the night.

At daybreak, 25 miles south of the capital, Dr. Mudd awoke to a

knock at the door. “Who’s

there, Mudd asked sleepily?”

The voice at the door said, “I have an injured man in need of a doctor.”

The voice belonged to David Herold, who that night taken part in

the unsuccessful attempt at killing Sec. Seward.

Leaning on Herold shoulder was John Wilkes Booth disguised behind

a false beard and a shawl wrapped around his face.

The man broke his leg falling off a horse, Herold said.

Did the doctor recognize Booth?

He had met Booth five months before, when Booth said he was

looking over property in the neighborhood.

He was actually planning an escape route for his abduction plan.

According to one trial witness, whose reputation is in doubt,

Mudd had met Booth in Washington DC at even a later date.

Because of supposed prior meetings, Mudd was charged with

Lincoln’s assassination. The

charge seemed rather thin because it was unlikely that a broken leg was

part of Booth’s plan. Mudd

did not learn of Lincoln’s death until later that day.

By that time Booth and Herold had already left Dr. Mudd’s house.

It was not generally known that Booth had been the man who had

shot the president. The war

department had covered up the name of the assassin, even to the point of

censoring it to press dispatches.

Mudd had acted as any caring doctor would.

He slipped open Booth’s boot.

He then set the bone and put him to bed.

Booth and Herold stayed at Mudd’s house for most of Saturday.

At one-point Mudd tried to borrow a wagon so that his patient

could continue his travels in comfort.

But he failed to secure one.

Booth wanted a razor to shave off his mustache, so Mudd loaned

him one. The doctor then

left his house to attend other patients.

boots, walked behind Lincoln and shot him through the head.

Major Rathbone jumped out of his seat and attempted,

unsuccessfully, to grapple with the assailant.

Booth attacked him with a knife and then jumped over the

balustrade catching a spur on the flag adorning the box.

He fell heavily to the stage some 12 feet below.

A bone in his left leg snapped.

Despite his injury, and despite being in pain, Booth hobbled out

a side door and rode off on horseback through the night.

At daybreak, 25 miles south of the capital, Dr. Mudd awoke to a

knock at the door. “Who’s

there, Mudd asked sleepily?”

The voice at the door said, “I have an injured man in need of a doctor.”

The voice belonged to David Herold, who that night taken part in

the unsuccessful attempt at killing Sec. Seward.

Leaning on Herold shoulder was John Wilkes Booth disguised behind

a false beard and a shawl wrapped around his face.

The man broke his leg falling off a horse, Herold said.

Did the doctor recognize Booth?

He had met Booth five months before, when Booth said he was

looking over property in the neighborhood.

He was actually planning an escape route for his abduction plan.

According to one trial witness, whose reputation is in doubt,

Mudd had met Booth in Washington DC at even a later date.

Because of supposed prior meetings, Mudd was charged with

Lincoln’s assassination. The

charge seemed rather thin because it was unlikely that a broken leg was

part of Booth’s plan. Mudd

did not learn of Lincoln’s death until later that day.

By that time Booth and Herold had already left Dr. Mudd’s house.

It was not generally known that Booth had been the man who had

shot the president. The war

department had covered up the name of the assassin, even to the point of

censoring it to press dispatches.

Mudd had acted as any caring doctor would.

He slipped open Booth’s boot.

He then set the bone and put him to bed.

Booth and Herold stayed at Mudd’s house for most of Saturday.

At one-point Mudd tried to borrow a wagon so that his patient

could continue his travels in comfort.

But he failed to secure one.

Booth wanted a razor to shave off his mustache, so Mudd loaned

him one. The doctor then

left his house to attend other patients.

At this point, Booth and Herold continued on horseback into the swamps.

As Booth was leaving his false beard slipped and Mrs. Mudd became

suspicious. Dr. Mudd told

acquaintances what he knew about the strangers.

But it was not until Tuesday, four days after the assassination,

did soldiers come to question Mudd.

It was not until the end of the week that Mudd was jailed.

He was jailed under the assumption that Mudd aided the escapee.

Booth and Herold remained in the swamp a dozen miles to the

south. They were aided by a

plantation owner, Col. Samuel Cox, and his foster brother Thomas Jones.

Jones eventually helped Booth and Herold to cross the Potomac one

night in a rowboat. The two

of them traveled briefly with two pardoned Confederate soldiers.

Booth and Herold stopped the night of April 25, 1865 at the farm

of Richard Garrett. They had

crossed into Virginia and then crossed the Rappahannock River.

It was there that federal troops finally cornered Booth and

Herold sleeping in Garrett’s tobacco barn.

“Surrender, a lieutenant cried!

Or we’ll fire the barn and smoke you out like rats”

Herold through down his gun and walked out.

Booth refused to give in so easily.

The barn was set on fire and to everyone’s surprise, the building

went up in a flash. The barn

was filled with wooden furniture stored by the Garrett’s for their

neighbor. The flames nearly

engulfed Booth and he spun around to make a quick break for the door.

As Booth made for the door, Sgt. Corbett thought Booth was going

to shoot him. So, he shot

Booth who fell forward on his face.

The bullet went through his neck, cutting the spinal cord.

He was taken up to the porch of the Garrett house and his famous

last words were: “Tell my mother I died for my country.”

He asked if his hands would be raised and they were.

He exclaimed: “useless, useless.”

Just Booth’s blood was not enough for the

country, somebody must suffer for it.

So, Dr. Mudd and several others were bought before a military tribunal.

And this caused a lot of problems too.

A lot of people believe that the defendant should not have been

tried by a military tribunal, but a civil court.

The prosecution claimed that Dr. Mudd not only set Booth’s leg,

but was part of the criminal conspiracy.

The defense countered these charges.

After the trial four conspirators were taken off to be hanged,

and four others were sent to Fort Jefferson prison in Florida.

They were originally set to be sent to the prison in Albany, New

York, but, because of the outcry about a military trial, they were sent

instead to Fort Jefferson.

There, there would be less chance of a civilian court setting them free.

At first Dr. Mudd was incredulous that such a disaster could

befall him. “Oh, there is no

hope for me.” He was

reported to have said. “I

cannot live in such a place.”

At Fort Jefferson,

Dr. Mudd was assigned duties in the prison hospital.

At first, he seemed hopeful that his wife and friends would

successfully appeal his case, or receive a pardon from President

Johnson. Although Johnson so

much as admitted that Mudd was innocent, he would not release him.

Public opinion is too strong against such mercy at this time said

the president. Of course,

Johnson had his own problems.

He was fighting people who wanted to impeach him.

There were also people who suggested that he and Sec. Stanton

were part of the conspiracy.

several others were bought before a military tribunal.

And this caused a lot of problems too.

A lot of people believe that the defendant should not have been

tried by a military tribunal, but a civil court.

The prosecution claimed that Dr. Mudd not only set Booth’s leg,

but was part of the criminal conspiracy.

The defense countered these charges.

After the trial four conspirators were taken off to be hanged,

and four others were sent to Fort Jefferson prison in Florida.

They were originally set to be sent to the prison in Albany, New

York, but, because of the outcry about a military trial, they were sent

instead to Fort Jefferson.

There, there would be less chance of a civilian court setting them free.

At first Dr. Mudd was incredulous that such a disaster could

befall him. “Oh, there is no

hope for me.” He was

reported to have said. “I

cannot live in such a place.”

At Fort Jefferson,

Dr. Mudd was assigned duties in the prison hospital.

At first, he seemed hopeful that his wife and friends would

successfully appeal his case, or receive a pardon from President

Johnson. Although Johnson so

much as admitted that Mudd was innocent, he would not release him.

Public opinion is too strong against such mercy at this time said

the president. Of course,

Johnson had his own problems.

He was fighting people who wanted to impeach him.

There were also people who suggested that he and Sec. Stanton

were part of the conspiracy.

Dr. Mudd became disillusioned with the injustice and cruel treatment.

So, in September 1865 he attempted to flee, as prisoners were

constantly escaping from the fort.

Mudd did not have their subterfuge.

Also, other prisoners were not as famous as he was, and would not

be so quickly missed. He

managed to sneak outside the fort into the hull of a transport.

Ten minutes later, soldiers found him and threw him in irons.

Although Dr. Mudd spent most of his sentence in chains, he did

not regret the loss of his hospital privileges.

He wrote to his wife, it depressed him to see prisoners with

minor illnesses dying because of improper nutrition.

Two years later, in August 1867, the first cases of yellow fever

appeared in the barracks on the south side of the fort.

Two soldiers died within days.

At that time mosquitoes had not been identified as the cause of

yellow fever. So, the only

precaution to be taken was quarantine.

The disease would not be so easily contained.

It began to sweep the fort spreading from the south side.

Yellow fever, so many people believe that this time, was an

infectious disease. You had

to destroy the contaminated clothing.

It is interesting to note at one time the Confederates considered

the use of germ warfare by dumping “infected clothing” in northern

cities. Obviously, such

plans were doomed to failure as mosquitoes, and not infected clothes,

were the culprits. At Fort

Jefferson southern breezes carried the mosquitoes and the disease along

almost predictable paths.

Soldiers and prisoners living in the path began to fall like dominoes.

One of his fellow prisoners said, “Doctor, yellow fever is the

fairest and squarest thing that I have ever seen in the past four or

five years. It makes no

distinction as to rank, color, or previous conditions.

Every man has his chance and I would advise you as a friend not

to interfere.” Mudd, as a

doctor, had to interfere.

Seventeen days after the big epidemic’s outbreak prison surgeon Smith

died of yellow fever. The

commanding officer, Maj. Stone, reluctantly asked Dr. Mudd to manage the

hospital until the arrival of another surgeon.

But, before Dr. Mudd could be asked he was already hard at work,

volunteering his services.

Upon taking charge, Dr. Mudd immediately changed treatments and

procedures. Newly stricken

patients were taken by boat to Sandy Key, two and half miles away.

Aware that only instant attention could halt the disease’s

advance, Mudd treated the victims of the disease immediately within the

fort. Dr. Mudd contracted

the disease himself, but recovered.

During the weeks that he took charge of the prison hospital, Dr.

Mudd proved to be an effective doctor.

Not one of his patients died.

It appeared that Dr. Mudd would soon be rewarded.

Following the death of Maj. Stone’s wife, the Commandant of the

prison left the island with his two-year-old son.

Maj. Stone promised that when he got to Washington he would seek

a pardon for Mudd. But, when

Maj. Stone arrived in Key West, he contracted yellow fever and died.

At Fort Jefferson, the soldiers and prisoners signed a petition

requesting Dr. Mudd’s release.

But, when a new Commandant arrived at the fort Mudd was again

thrown into chains. Dr. Mudd

totally despaired of ever getting a release.

Meanwhile, Dr. Mudd’s wife and friends continue their pleas for justice.

If they couldn’t get justice, at least they could try for

clemency. By now the public

that have been so quick to thirst for the blood of the conspirators

almost four years ago had somewhat forgotten about it, or had lost

interest. The impeachment

action against President Johnson had failed.

In 1869, just before leaving office, Johnson signed a pardon for

Dr. Mudd. Dr. Mudd returned

home broken in spirit and weakened in health.

Fourteen years later, he died of pneumonia, a disease he

contracted by visiting a patient.

However, the story does not end there.

In October 1959, Congress passed and President Dwight Eisenhower

signed into law a bill providing for a bronze memorial to be placed in

Fort Jefferson. This was to

commemorate Dr. Mudd’s service to the victims of yellow fever.

In 1979, President Jimmy Carter issued a proclamation absolving

Mudd of any complicity in the assassination of President Lincoln.

It should be noted that Dr. Mudd’s grandson worked for 50 years

to clear his grandfather’s name.

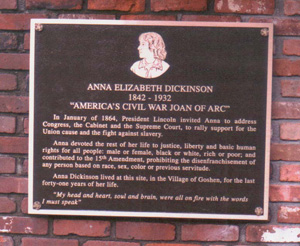

Anna Elizabeth Dickinson

by Gerridine LaRovere

Anna

Elizabeth Dickinson was born on October 28, 1842 in Philadelphia, PA to

Quakers. She had three older

brothers and one older sister, Susan.

Her father died in 1844 after giving a speech against slavery.

Left in poverty, her mother opened a school in her home and took

in boarders. Anna was

educated at the Friends Select School of Phila. and went for a brief

time to Westtown School. She

was an excellent student.

When she earned extra money, she bought books especially the classics.

At the age of 14, Anna converted to the Methodist Church and

remained active in the church throughout her life. Anna

Elizabeth Dickinson was born on October 28, 1842 in Philadelphia, PA to

Quakers. She had three older

brothers and one older sister, Susan.

Her father died in 1844 after giving a speech against slavery.

Left in poverty, her mother opened a school in her home and took

in boarders. Anna was

educated at the Friends Select School of Phila. and went for a brief

time to Westtown School. She

was an excellent student.

When she earned extra money, she bought books especially the classics.

At the age of 14, Anna converted to the Methodist Church and

remained active in the church throughout her life.

Not yet 14, Anna had an essay

published in the

Liberator, a newspaper owned by William Lloyd

Garrison, and discussed the abuse an abolitionist school teacher

received in Kentucky. At 15

she went to work as a copyist.

For two years she taught school in Berks County, PA.

In 1861, she obtained a clerkship for the U.S. Mint and was the

mint’s first female employee.

However, in December she was asked to leave.

At a public meeting Anna derided the military performance of

General George McClellan and that was grounds for dismissal.

Quakers encouraged women to speak in

public. At the time this was

not the norm in American society.

Lucretia Mott and Dr. Hannah Longshore were guiding forces in her

life. Anna spoke without

notes and gave impassioned speeches on abolition, reconstruction,

women’s rights and temperance.

Although only five feet two inches tall, she could speak

passionately to large crowds and rankle her audience as she did time and

time again. The

mezzo-soprano with the gray eyes made her first public speech to the

Pennsylvania Anti-slavery Society in 1860.

A year later, with the help of Lucretia Mott, 800 people bought

tickets to hear her talk in Philadelphia Concert Hall entitled

The Rights and Wrongs

of Women.

Then William Lloyd Garrison, founder and editor the Boston

abolitionist newspaper, the

Liberator, brought her to lecture at Boston

Music Hall. After that

engagement her ability spread throughout the North. Anna quickly became

a very popular speaker. Her

series of speeches greatly influenced the emancipation movement.

Lucretia Mott arranged a lecture tour for her sponsored by the

Mass. Antislavery Society.

By 1862, she toured the country on

behalf of the Sanitary Commission and visited wounded soldiers. She even

gave lectures called

Hospital Life.

She was pleased with these presentations because it helped to

support her widowed mother and three siblings.

During the 1863 state elections, partisan politics were deepening

in the country. There were

pro-Union Republicans and anti-war Democrats and vice versa.

Although many people were becoming weary of the War, both parties

wanted victory at almost any cost.

Anna spoke eloquently and powerfully in support of pro-Union

Republicans and the anti-slavery movement.

Anna was named the War’s “Joan of Arc” for her promotion of the

Union.

On March 24, 1863. Anna Elizabeth

Dickenson arrived in Hartford, CT by train from Philadelphia.

Although, most young women had a chaperone when they traveled,

Anna was by herself. The

twenty-year-old Quaker was invited by the Connecticut Republicans and

they paid her expenses. The

reason for her visit raised many an eyebrow.

She was to speak and rally support for the Union war effort, and,

more importantly, get the vote out to re-elect Connecticut’s Republican

governor. This talk

solidified her reputation as orator and lecturer.

The Republicans agreed to pay her

$100.00 per speech (in today’s dollars about $1200.00).

The job allowed her to fulfill other goals.

“I took the platform because I had something to say.

We Quakers only talk when the spirit moves us.

My head and heart, soul and brain, were all on fire with the

words I must speak”, she recalled.

Raised by orthodox Quaker parents she was taught that slavery was

a greater evil than war and war must have seemed the only way to end it.

Connecticut’s gubernatorial election

was less than two weeks away and there was a strong anti-war sentiment. Governor William A. Buckingham was in despair.

Political pundits were forecasting his defeat by 10,000 votes.

There were no polls taken at the time.

The democratic opponent, former Governor Thomas H. Seymour, was

clamoring for peace at any cost.

There was a national epidemic of war weariness.

sentiment. Governor William A. Buckingham was in despair.

Political pundits were forecasting his defeat by 10,000 votes.

There were no polls taken at the time.

The democratic opponent, former Governor Thomas H. Seymour, was

clamoring for peace at any cost.

There was a national epidemic of war weariness.

“Rally meetings were all the rage,”

according to the Springfield newspaper.

In Hartford and New Haven large gatherings were held every night.

James G. Batterson, founder of Travelers Insurance Company, was chairman

of the Connecticut Republican party.

He took the gamble on Anna on the advice of several New Hampshire

politicians who saw her speak.

Crowds trudged through heavy snows to hear her talk for two hours

without any notes and roused the crowds with great enthusiasm.

Many influential Republicans worried

about the prospect of relying on a mere “woman” to do something so

important that a man traditionally did.

“I shall never forget the dismay at the announcement of her first

speech in our conservative and prejudiced city,” wrote Isabella Beecher

Hooker. She was the

half-sister of Harriet Beecher Stowe.

After arriving in Hartford on March

24th Anna sat for courtesy photos at the

Main Street Studio. Although

outwardly confident, she had panic attacks before she spoke.

This evening she donned her black dress and brushed her dark

curls as she mustered all the verve she needed for a highly charged

political atmosphere. The

Democratic press took jabs at her and wrote, “Poor Republicans actually

procure a woman for aid.”

While other speakers’ names were listed in very large type, Anna’s was

in very small letters in the program and posters.

There were 1500 spectators inside

Touro Hall, a former church that was rented for the rally. At 7:30 the

highly animated Anna started to speak and ignited the hopes of the

Republicans. She spoke passionately and quickly about the ideas on the

Republican agenda.

In addition to the speech in

Connecticut, Anna spoke over a dozen times in Massachusetts, Rhode

Island, and New Hampshire.

Enthusiasm rather than logic seemed to be her strength. These are

remarks from one of her talks: “The head of the people of the 19th century requires the reason for

war. The heart of the people

of the U.S., with their Constitution-the safeguard of liberty-they

demand answer! And what

answer shall be given unto them?

Slavery! Slavery!

Proven, we think to be so, beyond cavil or doubt or question.

If then slavery is the cause-the originator, the upholder of the

rebellion-sweep aside the cause.

Strike down the originator. Crush the upholder.

Kill slavery!”

People were impressed with her

speeches. In an article written in the Hartford Newspaper, “Hartford has

been astonished to listen to what a woman could say about politics.”

Pouring rain came down on March 25, 1863, but this did not

prevent large audiences turning out in various towns.

Anna wrapped up her speeches by persuading listeners to join a

pro-war group known as Loyal Women’s League.

Isabella Beecher Hooker took a leading role in this organization.

The Republican Party leaders were no

longer apprehensive about Anna and started posting her name at the head

of all official announcements for party rallies when she spoke.

She filled every auditorium and very often people could not get a

seat.

There were many who opposed her in

the towns she visited.

Democrats condemned the idea that a woman could popularize any cause.

In Middletown, 2000 people gathered in a Hall and pranksters

dimmed the gas lights and set off the fire alarm.

One of her topics was about Irish immigrants who came to America

and escaped the ten cents-a-day wages in Ireland.

From the back row someone shouted, “That’s all we get now!”

She retorted, “Then you must work for a Democrat!”

Criticism came from other states.

New York newspapers begged Connecticut to stop this “very

ridiculous” female exhibitionist.

Another newspaper said that Anna would soon be offering kisses in

exchange for Republican votes.

An editorial in the Hartford newspaper stated that a woman’s

organization “would destroy the happiness of society.”

April 4th was the eve of the gubernatorial

election. Anna would speak

in Hartford one more time and admonished women to stay cheerfully at

home and save room for white men.

However, 300 women came, and they were refused entrance.

Anna insisted that the ladies be seated and they were.

She implored the Union to continue the War in order to crush

slavery and “the Confederacy will be ground to powder.”

Voters came to the polls on April 5th and William Buckingham was

reelected governor by 2,633 votes.

As she left Hartford for New York, a band gave a concert in her

honor. Party leaders gave

her a $400.00 bonus and rewarded her with two powerful male symbols: a

pocket watch and chain and a colt revolver.

Last changed: 10/22/18 |