The President’s Message:

If you have an idea for a program or can suggest a guest

speaker, please contact me.

Gerridine LaRovere

June 13, 2018 Program:

The June speaker will be Cindy Morrison and the presentation

will be

Teamsters and Waggoneers.

The North used

railroads to carry men, heavy weapons, and other supplies.

But, each army had to carry with them supplies to use on a daily

basis. Those supplies were

carried in supply trains.

Supply trains were made up of wagons, horses, mules, and teamsters who

were the drivers. A teamster

was a soldier and his job was very dirty and dangerous.

When a wagon was empty, the teamster was sent back to a supply

base to reload and return to the march or the camp.

May 9, 2018 Program:

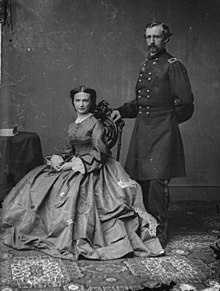

Cynthia Morrison,

Davis Rafaidus and Miriam Rafaidus presented a program about George

Armstrong Custer. David and Miriam did a brief scene between George and

Libby Custer about his posting to Little Big Horn. Cynthia and David

spoke about Custer’s life. A lively discussion followed afterward.

Custer’s childhood

ambition was to be a soldier.

Custer’s father, a blacksmith and farmer, migrated westward to

Ohio and Michigan. His father did nothing to discourage his hopes and

saw to it that his son received sufficient education to qualify for a

West Point cadetship.

Never much of a

student, Custer graduated 34th in the 34-man class

of 1861 and proceeded directly to the battlefield.

He fought with the Union’s 5th Cavalry at Bull Run

and later served on the staffs of Philip Kearney, William F. Smith, and

George McClellan. During the

Peninsular Campaign of 1862 , one of his staff assignments involved

supervision of balloon reconnaissance.

Promotion came swiftly, and Custer won his brigadier’s star after

leading a spirited cavalry charge at Aldie in June 1863.

He commanded the Michigan Brigade of the 3rd Cavalry Division at

Gettysburg, taking part in a sharp encounter with Wade Hampton’s

Confederate cavalry on the second day of the battle.

Tall, lithe, with

ringlets of yellow hair, he was always something of an exhibitionist.

He liked to think of himself as dashing but others often found

him absurd. Wearing an

elaborate uniform, Theodore Lyman thought he looked “like a circus rider

gone mad.” He was undeniably

courageous, excelling in such hell-for-leather operations with Philip

Sheridan and the raid toward Richmond in May 1864.

Custer advanced to within four miles of the Confederate capital.

Custer, along with

Sheridan, fought at the Dinwiddie Courthouse. In his greatest triumph,

he led the advance in Sheridan’s relentless final pursuit of Lee’s army

westward to Appomattox and received the first flag of truce from the

Army of Northern Virginia.

In a farewell order to his division shortly after Lee’s surrender,

Custer claimed his command had captured 111 pieces of artillery, 65

battle flags, and 10,000 prisoners.

After the war Custer

served in Texas and later became lieutenant colonel of the 7th Cavalry.

His first experience fighting Indians was against the Cheyenne in

the spring of 1867. On

November 27, 1868, Custer attacked and destroyed a large Cheyenne

village of the Washita River in the Oklahoma territory, a bitter and

bloody defeat that forced the Cheyenne to return to their reservation.

From 1871 to 1873 he

served the regiment in garrison in Elizabethtown, KY, where he wrote his

well-regarded memoir

My

Life on the Plains.

It showed a more thoughtful side of Custer, as did his efforts to

reform the Bureau of Indian Affairs, that was riddled with corruption.

He returned to the plains with the 7th Cavalry in 1873.

The regiment had its first encounters with the hostile Sioux

guarding the Northern Pacific Railroad.

Custer set out on his

last campaign on June 22, 1876, moving up the Rosebud River toward the

headwaters of the Little Big Horn.

On the morning of June 25 he divided his force into three parts

and prepared for offensive operations against Sioux and Cheyenne war

parties known to be in the area.

Custer led five companies up the right band of the Little Big

Horn and into a trap. A

Sioux force of some 2,500 warriors ambushed his command and, after three

hours of fighting, killed every man in it including Custer’s two

brothers.

On

February 9, 1864, Custer married Elizabeth Clift Bacon (1842–1933), whom he had first seen

when he was ten years old. He was introduced to her in November of1862,

while home on leave. She was

not impressed with him

and her father, Judge Daniel Bacon, disapproved of

Custer as a match. He was

only the son of a blacksmith and thought that his daughter could do

better. After Custer had

been promoted to the rank of brevet brigadier general he gained the

approval of Judge Bacon. He

married Elizabeth Bacon fourteen months after they formally met. On

February 9, 1864, Custer married Elizabeth Clift Bacon (1842–1933), whom he had first seen

when he was ten years old. He was introduced to her in November of1862,

while home on leave. She was

not impressed with him

and her father, Judge Daniel Bacon, disapproved of

Custer as a match. He was

only the son of a blacksmith and thought that his daughter could do

better. After Custer had

been promoted to the rank of brevet brigadier general he gained the

approval of Judge Bacon. He

married Elizabeth Bacon fourteen months after they formally met.

In November 1868, following the Battle of Washita River, Custer was alleged (by Captain Frederick Benteen, chief of scouts Ben Clark, and

Cheyenne oral tradition) to have unofficially married Mo-nah-se-tah, daughter of the Cheyenne chief Little Rock in the winter of 1868.

Mo-nah-se-tah gave birth to a child in January 1869, two months after

the Washita battle. Cheyenne

oral history tells that she also bore a second child, fathered by Custer

in late 1869. Some historian

believe that Custer had become sterile after contracting gonorrhea while

at West Point and that the father was his brother Thomas.

A descendant of the second child, who goes by the name Gail

Custer, wrote a book about the affair.

Clarke's description in his memoirs included the statement,

"Custer picked out a fine looking one and had her in his tent every

night.

[Editor’s note:

Due to the fact that I could not attend this meeting, this brief

writeup was supplied most graciously by President Gerridine LaRovere.]

Last changed: 06/01/18

Home

About News

Newsletters

Calendar

Memories

Links Join

|