The President’s Message:

Thank you to Harold Teltser, Ted Gerson, and Joel Gordon for supplying

the refreshments in June, July, and August. Your generosity is greatly

appreciated.

If you have any ideas for programs, please contact me.

Gerridine LaRovere

July 11, 2018 Program:

Peppy

Lizza was a former member of the PBCCWRT and has returned to us.

He has done many programs and will do this month's on the importance of

Civil War Music. Join him as he surveys the " Top Ten " hits from the

60's...well, the 1860's. He will also select songs that were oldies at

that time, as well as heartfelt ones that are still sung today.

June 13, 2018 Program:

Cinthia

Morrison gave a presentation entitled:

Teamsters, Muleskinners, and Bullwhackers of the Civil War.

The North used railroads to carry men, heavy weapons, and other

supplies. But each army had

to carry with them supplies to use on a daily basis.

Those supplies were carried in supply trains.

Supply trains were made up of wagons, horses, mules, and

teamsters who were the drivers.

When a wagon was empty, the teamster was sent back to a supply

base to reload and return to the march or the camp.

A teamster had to reload his wagon with the same type of supply

he had carried before.

General Sherman's supply train consisted of over 5,000 wagons, 800

ambulances, 28,000 horses, and 32,000 mules.

His supply train stretched for miles, as did many supply trains

that served the Northern regiments. Cinthia

Morrison gave a presentation entitled:

Teamsters, Muleskinners, and Bullwhackers of the Civil War.

The North used railroads to carry men, heavy weapons, and other

supplies. But each army had

to carry with them supplies to use on a daily basis.

Those supplies were carried in supply trains.

Supply trains were made up of wagons, horses, mules, and

teamsters who were the drivers.

When a wagon was empty, the teamster was sent back to a supply

base to reload and return to the march or the camp.

A teamster had to reload his wagon with the same type of supply

he had carried before.

General Sherman's supply train consisted of over 5,000 wagons, 800

ambulances, 28,000 horses, and 32,000 mules.

His supply train stretched for miles, as did many supply trains

that served the Northern regiments.

A horse can generally pull three times its weight on good surfaces, two

times its weight on bad or hilly surfaces.

Since the average horse weighs about 900 to 1,100 pounds that's

about 3,000 pounds on good roads, 1,900 on bad roads, and maybe 1,000 on very bad

roads or steep ground.

pounds on good roads, 1,900 on bad roads, and maybe 1,000 on very bad

roads or steep ground.

At best a battery could make about five miles an hour on good, level

surfaces and with good horses but not for sustained periods.

About two miles per hour for six hours (i.e. 15 miles per day)

would have been average and twenty to twenty-five miles per day would

have been the typical maximum.

The average artillery horse lasted about eight months.

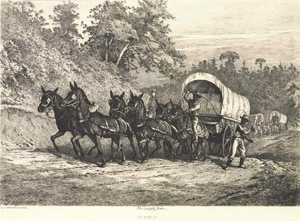

Teamsters of the day can be divided by the animals they drove.

The muleskinners worked the mule

teams.

They usually rode on the backs of the last set of animals in the

team as illustrated in the image.

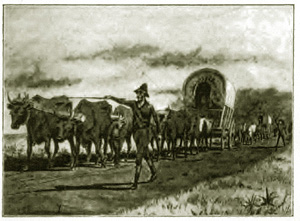

Bullwhackers drove teams of oxen.

Unlike the muleskinners, they walked beside their teams. teams.

They usually rode on the backs of the last set of animals in the

team as illustrated in the image.

Bullwhackers drove teams of oxen.

Unlike the muleskinners, they walked beside their teams.

Cindy touched briefly on teamsters in Florida.

In hopes of disrupting food supplies to the Confederate troop,

the blockading ships around the coast of Florida sent raider up the bays

and streams. Of necessity

these raids were small in number as they had to come inland by small

draft boats. To counter

this threat, the ranchers formed military units referred to as the “cow

cavalry.”

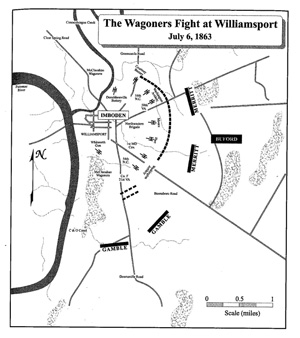

The last story she related to us was about the role BG John Imboden

played in the retreat from Gettysburg.

Lee’s army was up against a high river near Williamsport, PA.

Improvising reinforcements, Imboden organized about 700 of his

wagoners into infantry companies under wounded officers, and

commissaries and quartermasters.

He positioned these makeshift soldiers on his right and left

flanks and then bolstered the center of his line with 2,100 dismounted

cavalrymen and 24 cannons, establishing a three-mile perimeter on a

crescent-shaped ridge a half-mile west of Williamsport.

There they held off the Union cavalry under the command of BG

John Buford. For a more

complete story about this engagement see The

Retreat from Gettysburg

below. This has been

reproduced from Imboden’s own memoirs written in 1887.

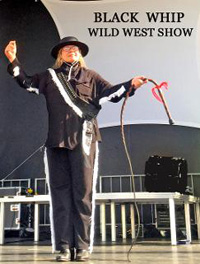

At the end of her presentation, Cindy put on a demonstration of whip

artistry. While explaining

that the whip was not to beat the animals, but to get their attention.

The crack of a whip is actually a sonic boom as the end of the

whip goes supersonic. She

gave hints of her very colorful past as an escape artist, a ren-faire

performer, a knife thrower, and of course whip artist.

Ms. Morrison’s talk was applauded at its conclusion.

The Retreat from Gettysburg, by Brig. General John Imboden C.S.A. (1887)

During the Gettysburg campaign, my command an independent brigade of

cavalry was engaged, by General Lee’s confidential orders, in raids on

the left flank of his advancing army, destroying railroad bridges and

cutting the canal below Cumberland wherever I could so that I did not

reach the field till noon of the last day’s battle. I reported direct to

General Lee for orders and was assigned a position to aid in repelling

any cavalry demonstration on his rear. None of a serious character being

made, my little force took no part in the battle, but was merely

spectators of the scene, which transcended in grandeur any that I beheld

in any other battle of the war.

When night closed the struggle, Lee’s army was repulsed. We all knew

that the day had gone against us, of the disaster was only known in high

quarters. The carnage of the day was generally understood to have been

frightful, yet our army was not in retreat, and it was surmised in camp

that with tomorrow’s dawn would come a renewal of the struggle. All felt

and appreciated the momentous consequences to the cause of Southern

independence of final defeat or victory on that great field.

[Editor’s note: The next

paragraphs tell about Lee’s orders for retreat and Imboden’s wagon

command.]

Shortly after noon of the 4th the very windows of heaven seemed to have

opened. The rain fell in blinding sheets; the meadows were soon

overflowed, and fences gave way before the raging streams. During the

storm, wagons, ambulances, and artillery carriages by hundreds by

thousands were assembling in the fields along the road from Gettysburg

to Cashtown, in one confused arid apparently inextricable mass. As the

afternoon wore on there was no abatement in the storm. Canvas was no

protection against its fury, and the wounded men lying upon the naked

boards of the wagon bodies were drenched. Horses and mules were blinded

and maddened by the wind and water and became almost unmanageable. The

deafening roar of the mingled sounds of heaven and earth all around us

made it almost impossible to communicate orders, and equally difficult

to execute them.

About 4 P. M. the head of the column was put in motion near Cashtown and

began the ascent of the mountain in the direction of Chambersburg. I

remained at Cashtown giving directions and putting in detachments of

guns and troops at what I estimated to be intervals of a quarter or a

third of a mile. It was found from the position of the head of the

column west of the mountain at dawn of the 5th, the hour at which

Young’s cavalry and Hart’s battery began tile assent of the mountain

near Cashtown, that the entire column was seventeen miles long when

drawn out on the road and put in motion. As an advance guard I had

placed the 18th Virginia Cavalry, Colonel George W. Imboden in front

with a section of McClanahan’s battery.

Next to them, by request, was placed an ambulance carrying, stretched

side by side, two of North Carolina’s most distinguished soldiers,

Generals Pender and Scales, both badly wounded, but resolved to bear the

tortures of the journey rather than become prisoners. I shared a little

bread and meat with them at noon, and they waited patiently for hours

for the head of the column to move. The trip cost poor Pender his life.

General Scales appeared to be worse hurt, but stopped at Winchester,

recovered, and fought through the war.

[Editor’s note: The next

paragraphs tell about the pitiful condition of the wounded.]

We were now twelve or fifteen miles from the Potomac at Williamsport,

our point of crossing into Virginia.

Here our apprehended troubles began. After the advance of the

18th Virginia Cavalry had passed perhaps a mile beyond the town, the

citizens to the number of thirty or forty attacked the train with axes,

cutting the spokes out of ten or a dozen wheels and dropping the wagons

in the streets. The moment I heard of it I sent back a detachment of

cavalry to capture every citizen who had been engaged in this work and

treat them as prisoners of war. This stopped the trouble there, but the

Union cavalry began to swarm down upon us from the fields and

crossroads, making their attacks in small bodies, and striking the

column where there were few or no guards, and thus creating great

confusion. I had a narrow escape from capture by one of these parties of

perhaps fifty men that I tried to drive off with canister from two of

McClanahan’s guns that were close at hand. They would perhaps have been

too much for me; had not Colonel Imboden, hearing the firing turned back

with his regiment at a gallop, and by the suddenness of his movement

surrounded and caught the entire party.

To add to our perplexities still further, a report reached me a little

after sunrise, that the Federals in large force held Williamsport. I did

not fully credit this and decided to push on. Fortunately, the report

was untrue. After a great deal of desultory fighting and harassments

along the road during the day, nearly the whole of the immense train

reached Williamsport on the afternoon of the 5th. A

part

of it, with Hart’s battery, came in next day, General Young having

halted and turned his attention to guarding the road from the west with

his cavalry. We took possession of the town to convert it into a great

hospital for the thousands of wounded we had brought from Gettysburg. I

required all the families in the place to go to cooking for the sick and

wounded, on pain of having their kitchens occupied for that purpose by

my men. They readily complied. A large number of surgeons had

accompanied the train, arid these at once pulled off their coats and

went to work and soon a vast amount of suffering was mitigated. The

bodies of a few who had died on the march were buried. All this became

necessary because the tremendous rains had raised the river more than

ten feet above the fording stage of water, and we could not possibly

cross then. There were two small ferryboats or “flats” there, which I

immediately put into requisition to carry across those of the wounded,

who, after being fed and having their wounds dressed, thought they could

walk to Winchester. Quite a large number were able to do this, so that

the “flats” were kept running all the time. part

of it, with Hart’s battery, came in next day, General Young having

halted and turned his attention to guarding the road from the west with

his cavalry. We took possession of the town to convert it into a great

hospital for the thousands of wounded we had brought from Gettysburg. I

required all the families in the place to go to cooking for the sick and

wounded, on pain of having their kitchens occupied for that purpose by

my men. They readily complied. A large number of surgeons had

accompanied the train, arid these at once pulled off their coats and

went to work and soon a vast amount of suffering was mitigated. The

bodies of a few who had died on the march were buried. All this became

necessary because the tremendous rains had raised the river more than

ten feet above the fording stage of water, and we could not possibly

cross then. There were two small ferryboats or “flats” there, which I

immediately put into requisition to carry across those of the wounded,

who, after being fed and having their wounds dressed, thought they could

walk to Winchester. Quite a large number were able to do this, so that

the “flats” were kept running all the time.

Our situation was frightful. We had probably ten thousand animals and

nearly all the wagons of General Lee’s army under our charge, and all

the wounded, to the number of several thousand, that could be brought

from Gettysburg. Our supply of provisions consisted of a few wagonloads

of flour in my own brigade train, a small lot of fine fat cattle, which

I had collected in Pennsylvania on my way to Gettysburg, and some sugar

and coffee procured in the same way at Mercersburg.

The town of Williamsport is located in the lower angle formed by the

Potomac with Conococheagne Creek. These streams enclose the town on two

sides, and back of it about one mile there is a low range of hills that

is crossed by four roads converging at the town. The first is the

Greencastle road leading down the creek valley; next the Hagerstown

road; then the Boonsboro’ road; and lastly the River road.

Early on the morning of the 6th I received intelligence of the approach

from Frederick of a large body of cavalry with three full batteries of

six rifled guns. These were the divisions of Generals Buford and

Kilpatrick, and Huey’s brigade of Gregg’s division, consisting, as I

afterward learned, of 23 regiments of cavalry, and 18 guns, a total

force of about 7000 men.

I immediately posted my guns on the hills that concealed the town, and

dismounted my own command to support them and ordered as many of the

Wagoner’s to be formed as could be armed with the guns of the wounded

that we had brought from Gettysburg. In this I was greatly aided by

Colonel J. L. Black of South Carolina, Captain J. F. Hart commanding a

battery from the same State, Colonel William II. Aylett of Virginia, and

other wounded officers. By noon about 700 Wagoner's were organized into

companies of 100 each and officered by wounded line officers and

commissaries and quartermasters, about 250 of these were given to

Colonel Aylett on the right next the river, about as many under Colonel

Black on the left, and the residue were used as skirmishers. My own

command proper was held well in hand in the center.

The enemy appeared in our front about half-past one o’clock on both the

Hagerstown, and Boonsboro’ roads, and the fight began. Every man under

my command understood that if we did not repulse the enemy we should all

be captured and General Lee’s army be ruined by the loss of its

transportation, which at that period could not have been replaced in

the Confederacy. The fight began with artillery on both sides. The

firing from our side was very rapid and seemed to make the enemy

hesitate about advancing. In a half hour J. D. Moore’s battery ran out

of ammunition, but as an ordnance train had arrived from Winchester, two

wagonloads of ammunition were ferried across the river and run upon the

field behind the guns, and the boxes tumbled out, to be broken open with

axes. With this fresh supply our guns were all soon in full play again.

As the enemy could not see the supports of our batteries from the

hilltops, I moved the whole line forward to his full view, in single

ranks, to show a long front on the Hagerstown approach. My line passed

our guns fifty or one hundred yards, where they were halted awhile, and

then were withdrawn behind the hilltop again, slowly and steadily.

Leaving Black’s Wagoner's and the Marylanders on the left to support

Hart’s and Moore’s batteries, Captain Hart having been put in command by

Colonel Black when he was obliged to be elsewhere, I moved the 18th

Virginia Cavalry and 62d Virginia Mounted Infantry rapidly to the right,

to meet and repel five advancing regiments (dismounted) of the enemy. My

three regiments, with Captain John H. McNeill’s Partisan Rangers and

Aylett’s Wagoner's, had to sustain a very severe contest. Hart, seeing

how hard we were pressed on the right, charged the enemy’s right with

his little command, and at the same time Eshleman with his eight

Napoleons advanced four hundred yards to the front, and got an

enfilading position, from which, with the aid of McClanahan’s battery,

he poured a furious fire into the enemy’s line. The 62d and Aylett,

supported by the 18th Cavalry, and McNeill, charged the enemy who fell

back sullenly to their horses.

Night was now rapidly approaching, when a messenger from Fitzhugh Lee

arrived to urge me to “hold my own,” as he would be up in a half hour

with three thousand fresh men. The news was sent along our whole line

and was received with a wild and exultant yell. We knew then that the

field was won, and slowly pressed forward. Almost at the same moment we

heard distant guns on the enemy’s rear and right on the Hagerstown road.

They were Stuart’s, who was approaching on that road, while Fitzhugh Lee

was coming on the Greencastle road. That settled the contest. The enemy

broke to the left and fled by the Boonsboro’ road. It was too dark to

follow. When General Fitzhugh Lee joined me with his staff on the field,

one of the enemy’s shells came near striking him. General Lee thought it

came from Eshleman’s battery, till, a moment later, he saw a blaze from

its gun streaming away from us.

We captured about 125 of the enemy who failed to reach their horses. I

could never ascertain the loss on either side. I estimated ours at about

125. The Wagoner's fought so well that this came to be known as “the

Wagoner's’ fight.” Quite a number of them were killed in storming a farm

from which sharpshooters were rapidly picking off Eshleman’s men and

horses.

My whole force engaged, Wagoner's included, did not exceed three

thousand men. The ruse practiced by showing a formidable line on the

left, then withdrawing it to fight on the right, together with our

numerous artillery, 23 guns, led to the belief that our force was much

greater. By extraordinary

good fortune we had thus saved all of General Lee’s trains. A bold

charge at any time before sunset would have broken our feeble lines, and

then we should all have fallen an easy prey to the Federals. The next

day our army arrived from Gettysburg, and the country is familiar with

the way it escaped across the Potomac on the night of the 13th of July.

Last changed: 06/28/18

Home

About News

Newsletters

Calendar

Memories

Links Join

|