The President’s Message:

Best wishes for a

very happy and healthy New Year to everyone.

I look forward to another great year of speakers in our wonderful

new facility.

Please remember that

dues are due in January.

Dues may be paid at the January meeting.

Gerridine LaRovere

January 9, 2019 Program:

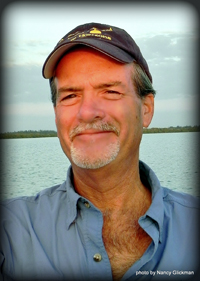

Joe Truglio will be the speaker at the January meeting. John Milton

Chivington-Hero of Glorieta Pass, Butcher of Sand Creek. This is a

presentation of the life of one of the most infamous characters in the

Civil War. He is still reviled to this day. We will look at his military

and civilian careers, his family life, and how he was thought of during

and after his lifetime. Our speaker, Joe Truglio, is the President of

the Phil Kearny CWRT in Wayne, NJ.

December

12, 2018 Program:

Once

again, and for the 16th

time, Robert Macomber gave his Civil War talk to our group.

It was entitled Key West’s critical role in the Civil War.

Bob mentioned that it was always a pleasure to speak before our

group. This is because he

need not explain a lot of the facts about the Civil War that are new to

outsiders. For example,

most of us knew that Florida was the third oldest Confederate state.

What many of us might not have known is that it was the state

that had the smallest population in the CSA.

This population was about 154,000 of which 93,000 were free and

62,000 were slaves. Of the

black population, 2,500 were free Blacks.

The people were centered in upper Florida, middle Florida, and

Key West. Once

again, and for the 16th

time, Robert Macomber gave his Civil War talk to our group.

It was entitled Key West’s critical role in the Civil War.

Bob mentioned that it was always a pleasure to speak before our

group. This is because he

need not explain a lot of the facts about the Civil War that are new to

outsiders. For example,

most of us knew that Florida was the third oldest Confederate state.

What many of us might not have known is that it was the state

that had the smallest population in the CSA.

This population was about 154,000 of which 93,000 were free and

62,000 were slaves. Of the

black population, 2,500 were free Blacks.

The people were centered in upper Florida, middle Florida, and

Key West.

There were 70 plantations of a thousand acres or more in the state.

They mostly produced cotton and sugar.

Upper and middle Florida were part of the South’s culture and

followed the commerce norms of the South.

Key West, on the other hand, was part of the Caribbean culture

and commerce. Bob mentioned

that, if you have the chance, you should visit Gamble Plantation in

Ellenton, Florida. It is

the only surviving plantation house in South Florida.

On the eve of the Civil War, Florida had only been a state or 15

years. It had come into the

union, along with Iowa, under the compromise that allowed slave states

to enter the union if paired with free states.

Key West was unique in a number of ways, on the eve of the Civil War.

It had a population of 2,400 people, the largest in Florida.

About 1/3 of this population were Cubans or Bahamians.

It had the highest per capita wealth in the state, due to

commerce and salvage. The

salvage operation was most interesting.

A good many citizens of the city owed their livelihood to the

profession of “wrecking.”

The art of wrecking involved saving as many of the crew of the ships

that had come to grief on the numerous reefs of the Florida Keys.

However, once the passengers and crew of the ships had been

saved, all of the cargo belong to the wreckers.

Thus, these good folks wanted nothing to do with building

lighthouses along the shore.

Of course, the ship owners and the insurance companies wanted the

United States to build lighthouses.

George G. Meade, of Gettysburg fame, was the designer and builder

of many of these lighthouses before the war.

Although he did not invent it, Meade made great use of the

screw-pile lighthouse. The

foundation of the lighthouse was stilts that had been screwed into the

coral. The coral then grows

around the screw piles, creating a strong foundation.

2,400 people, the largest in Florida.

About 1/3 of this population were Cubans or Bahamians.

It had the highest per capita wealth in the state, due to

commerce and salvage. The

salvage operation was most interesting.

A good many citizens of the city owed their livelihood to the

profession of “wrecking.”

The art of wrecking involved saving as many of the crew of the ships

that had come to grief on the numerous reefs of the Florida Keys.

However, once the passengers and crew of the ships had been

saved, all of the cargo belong to the wreckers.

Thus, these good folks wanted nothing to do with building

lighthouses along the shore.

Of course, the ship owners and the insurance companies wanted the

United States to build lighthouses.

George G. Meade, of Gettysburg fame, was the designer and builder

of many of these lighthouses before the war.

Although he did not invent it, Meade made great use of the

screw-pile lighthouse. The

foundation of the lighthouse was stilts that had been screwed into the

coral. The coral then grows

around the screw piles, creating a strong foundation.

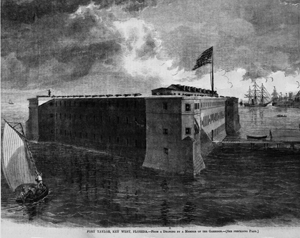

Bob

explained that Key West was the southernmost naval station and Army

fort. Two key

fortifications were started before the Civil War.

Fort Taylor was just off the coast of Key West.

It was about half built when the war began.

Fort Jefferson was built on Dry Tortuga 68 miles west of Key

West. It is interesting to

note that Fort Taylor was originally in the middle of the harbor

surrounded by water. The

only entrance was over a causeway that had a drawbridge.

It was sort of like a medieval castle with a moat.

Up until the Civil War, masonry forts like Jefferson and Taylor

were believed to be impregnable.

They certainly could not be taken by small arms alone.

Today the land around Fort Taylor has been filled in, with a

foundation of Civil War era cannons, and sand.

Therefore, Fort Taylor is no longer located in the harbor. Bob

explained that Key West was the southernmost naval station and Army

fort. Two key

fortifications were started before the Civil War.

Fort Taylor was just off the coast of Key West.

It was about half built when the war began.

Fort Jefferson was built on Dry Tortuga 68 miles west of Key

West. It is interesting to

note that Fort Taylor was originally in the middle of the harbor

surrounded by water. The

only entrance was over a causeway that had a drawbridge.

It was sort of like a medieval castle with a moat.

Up until the Civil War, masonry forts like Jefferson and Taylor

were believed to be impregnable.

They certainly could not be taken by small arms alone.

Today the land around Fort Taylor has been filled in, with a

foundation of Civil War era cannons, and sand.

Therefore, Fort Taylor is no longer located in the harbor.

The African Cemetery at Higgs Beach is a historical cemetery in Key

West. It contains the

graves of the Africans who died after being rescued in 1860 from captured slave

ships. Of the 1,500 slaves

who were liberated and brought back to Key West, 295 of them died and

are buried here. The living

were repatriated to Liberia.

There was much controversy about this, both then and now, because

the destination was nowhere near where the slaves were captured.

The cemetery is maintained by the Mel Fisher Maritime Museum.

of the Africans who died after being rescued in 1860 from captured slave

ships. Of the 1,500 slaves

who were liberated and brought back to Key West, 295 of them died and

are buried here. The living

were repatriated to Liberia.

There was much controversy about this, both then and now, because

the destination was nowhere near where the slaves were captured.

The cemetery is maintained by the Mel Fisher Maritime Museum.

Gov. John Milton was an early advocate for secession.

A convention was called for, to take up the issue of secession,

and on January 10, 1861, the measure passed.

The vote in Tallahassee passed 65 - 7.

Monroe County had three delegates to this convention and they

were all pro-secession.

16,500 Floridians were in military service from the spring of 1862.

They were in almost every major battle in the Civil War.

One out of three of these volunteers were casualties of war.

Florida had the highest volunteer ratio of any state in the

Confederacy. In this group

were 150 to 200 young men from Key West.

They join the Army in Tampa.

Among this group was 1st

Lieut. Walter C. Maloney, Junior, son of the mayor of Key West.

Lieut. Maloney served with the Florida brigade at Gettysburg.

In that battle, the brigade lost 65% of its members.

The mayor did not immediately find out that his son had survived

the battle.

Although

born in Trinidad, Stephen Mallory considered himself a native Floridian.

He was serving in the United States Senate when the war broke

out. Although not much of a

secessionist, Mallory remained true to his home state and join the

Confederates. Because he

was chairman of the committee on naval affairs, Mallory was raised to

the position of Secretary of the Navy for the CSA.

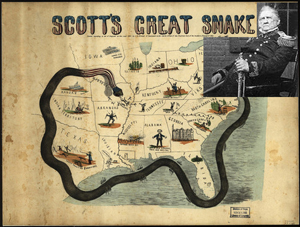

Naval operations were to play a key role in the story of Key West

and the Civil War. After

the fall of Fort Sumner in Charleston, Key West was the only port city

still in the hands of the Union.

Therefore, it was Key West, that was the focus of reinforcement.

It was to play a central role in Gen. Winfield Scott’s Anaconda

plan. This was the idea

that you could strangle the South by blockading the port cities.

At first this was hard to do because the union only had six

serviceable ships to carry out the plan.

They were sent to Key West. Although

born in Trinidad, Stephen Mallory considered himself a native Floridian.

He was serving in the United States Senate when the war broke

out. Although not much of a

secessionist, Mallory remained true to his home state and join the

Confederates. Because he

was chairman of the committee on naval affairs, Mallory was raised to

the position of Secretary of the Navy for the CSA.

Naval operations were to play a key role in the story of Key West

and the Civil War. After

the fall of Fort Sumner in Charleston, Key West was the only port city

still in the hands of the Union.

Therefore, it was Key West, that was the focus of reinforcement.

It was to play a central role in Gen. Winfield Scott’s Anaconda

plan. This was the idea

that you could strangle the South by blockading the port cities.

At first this was hard to do because the union only had six

serviceable ships to carry out the plan.

They were sent to Key West.

Before this grand scheme could get started, there was real issues on the

ground in Key West. Capt.

James M. Brannan of the first artillery was stationed at the barracks at

Key West. When he got word

that a meeting was being held to discuss secession, he wrote a letter to

Washington DC. He wanted to

know what he was to do in the event of secession.

He wrote this letter on December 11, 1860.

Since there was no telegraph in Key West, this request had to go

by sea. Having heard

nothing by January 13th,

this resourceful captain took matters into his own hands.

He ordered his 24 men and 13 workers into Fort Taylor, and pulled

up the drawbridge. The fort

was well supplied with ammunition, 70,000 gallons of water, and food for

three months. Although they

were few in number, and had even fewer rifles, this position was

impregnable. This is how

Key West became the linchpin of the Union naval strategy.

Thus, 36 men, one fort, and six naval ships began the blockade of

the South. Now that a few

men had secure Key West for the union, the real work of fortification

began. With resupply,

progress was made completing Fort Taylor.

Work is accelerated on the completion of Fort Jefferson too.

Navy supplies poured into Key West.

A full squadron was completed.

This became the East Gulf blockade squadron.

Army troops were brought in to occupy the forts and Key West.

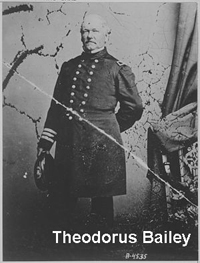

To

oversee naval operations, Rear Adm. Theodorus Bailey, the hero of the

Battle of New Orleans, assumed command.

Bailey, you will remember, brought his warships up to the dock in

New Orleans. With a small

contingent of marines, Bailey marched to the military headquarters in a

hotel and raise the Stars & Stripes on the flagpole at the top.

Thousands of the citizens of New Orleans, who could’ve easily

grabbed Bailey, stood idly by.

Bailey had said, you harm me or my men, and my warships will

level the town. This was

the no-nonsense guy who is now put in charge of executing the blockade.

Besides his excellent military skills, Bailey was a people

person. He got along well

with his superiors and his subordinates.

Unlike many in his position, Bailey worked well with the Army.

There were no turf battles in Key West.

Bailey started combined operations with the Army by putting

troops on shallow draft vessels and sending them up the small estuaries

on both coasts of Florida.

Under his command, the naval squadron triples in size to 38 vessels.

By the end of 1864, blockade running, was completely eliminated

in Florida. And, was almost

shut down everywhere else. To

oversee naval operations, Rear Adm. Theodorus Bailey, the hero of the

Battle of New Orleans, assumed command.

Bailey, you will remember, brought his warships up to the dock in

New Orleans. With a small

contingent of marines, Bailey marched to the military headquarters in a

hotel and raise the Stars & Stripes on the flagpole at the top.

Thousands of the citizens of New Orleans, who could’ve easily

grabbed Bailey, stood idly by.

Bailey had said, you harm me or my men, and my warships will

level the town. This was

the no-nonsense guy who is now put in charge of executing the blockade.

Besides his excellent military skills, Bailey was a people

person. He got along well

with his superiors and his subordinates.

Unlike many in his position, Bailey worked well with the Army.

There were no turf battles in Key West.

Bailey started combined operations with the Army by putting

troops on shallow draft vessels and sending them up the small estuaries

on both coasts of Florida.

Under his command, the naval squadron triples in size to 38 vessels.

By the end of 1864, blockade running, was completely eliminated

in Florida. And, was almost

shut down everywhere else.

The fact that Bailey got along with just about everyone else, didn’t

mean he was a pushover.

When one of his subordinates stepped out of line, Bailey came down hard on

him. A good example of this

was the story of one Col. Joseph S. Morgan of the 90th

NY. He zealously followed

orders from up north (Gen. Hunter in SC) to deport anyone with a family

member in the service of the CSA.

Morgan ordered every family member, who had a man in the Army of

the Confederacy, to register with the Army.

This added up to 752 citizens who were deported by ship in

February 1863. Sixteen of

Morgan's officers refused this draconian order and were placed under

arrest to await court-martial.

Bailey had no authority over army officers.

He wrote the president to have Morgan removed, but could not do

anything further. When Col

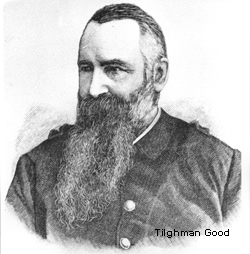

Tilghman Good of the 47th

Penn Infantry, fighting in South Carolina, heard about what was going on

in Key West he got Gen Hunter to order him back to Key West to

straighten out the rapidly worsening situation.

one of his subordinates stepped out of line, Bailey came down hard on

him. A good example of this

was the story of one Col. Joseph S. Morgan of the 90th

NY. He zealously followed

orders from up north (Gen. Hunter in SC) to deport anyone with a family

member in the service of the CSA.

Morgan ordered every family member, who had a man in the Army of

the Confederacy, to register with the Army.

This added up to 752 citizens who were deported by ship in

February 1863. Sixteen of

Morgan's officers refused this draconian order and were placed under

arrest to await court-martial.

Bailey had no authority over army officers.

He wrote the president to have Morgan removed, but could not do

anything further. When Col

Tilghman Good of the 47th

Penn Infantry, fighting in South Carolina, heard about what was going on

in Key West he got Gen Hunter to order him back to Key West to

straighten out the rapidly worsening situation.

Col Good's ship arrived the same day as the deportation ships were

loading. He and his

regiment took over, ordered Morgan regiment back to the barracks, and

the citizens back to their homes.

When the ship was brought back the 47th

Pennsylvania restored order.

Col Good and the men of the 47th

Penn were treated as heroes by the people of Key West.

In July 1863, the people of Key West presented Col Good with an

engraved gold sword from Tiffany's in New York as a token of their

appreciation for him saving them from deportation.

Mayor Maloney, who son was still serving in the Confederate army,

made the presentation. Can

you imagine how unusual this is for anoccupied town to honor an

occupying army unit?

Bailey held his position in Key West until the yellow fever epidemic in

the summer of 1864. Bailey

contracted the disease so he left for points north.

So many soldiers and sailors died, or were incapacitated by the

disease, that it was hard to conduct military operations either on land

or at sea. Bailey’s Army

counterpart, Brig. Gen. Daniel Phineas Woodberry, was stricken by the

fever and he died at his post.

Robert Macomber explains a great deal about the yellow fever

epidemic in his first novel in the honors series called

At the Edge of Honor.

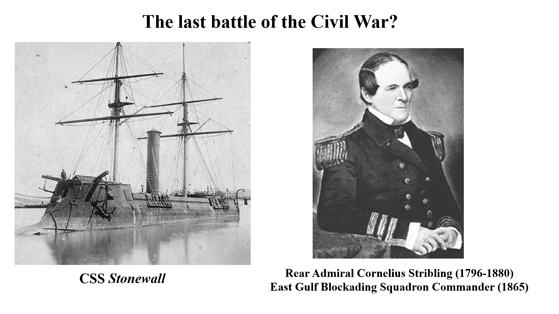

Robert ended his presentation with the amazing story of the capture of

CSS

Stonewall.

This ship was built, near the end of the war, by the French.

It headed across the Atlantic with Capt. TJ Page in command.

This formidable warship was state-of-the-art in 1865.

It boasted one 300 pounder main gun with 2 70 pounder guns in a

turret on the after deck.

She was sheathed in thick steel and had a powerful steel ram attached to

the bow.

Stonewall

could sink any ship afloat.

One day in May, 1865, CSS

Stonewall

showed up in Havana harbor.

The commander of the East Gulf blocking squadron, Adm. CK Stribling,

sent a detachment of three small warships to deal with the rebel

dreadnought. This was

clearly a suicide mission.

Stribling, however, was not without a plan.

He sent a note to the captain of the warship, offering generous

terms of surrender. Capt.

Page knew that the war was over.

Stribling made it clear that

Stonewall

was a ship without a flag, and therefore a pirate vessel.

In a face-saving mode, Page sold the ship to the Spanish governor

of Cuba. With the money

from the sale, the crew was paid and the captain and his men quietly

made their exit from the scene.

The Spanish then resold the vessel to the US government for what

he had paid the Confederate captain.

And thus, a bloodied engagement was avoided.

Last changed: 1/2/19 |