Volume 33, No. 9 –

September, 2020

The President’s Message:

I hope that everyone

is healthy, safe, and taking all the proper precautions to do so. I

know that we are all anxious to attend a Round Table meeting.

However, COVID-19 is preventing us from doing that. As soon as

circumstances permit a meeting will be scheduled.

Until we meet in person again, would any members be interested in

participating in a zoom meeting via the computer? Please call or

email me with your thoughts so we can plan accordingly.

Many of us are knowledgeable about well-known generals that served

during the War. Getting to Know the Generals spotlights known

personalities who had interesting careers during and after the

conflict. Sometimes information on a particular general is easy to

find and others such as Marcus Joseph Wright required extensive

research. If you have any additional information on any of the

generals featured, please send it to me.

Gerridine LaRovere

President

Get to Know the

Generals

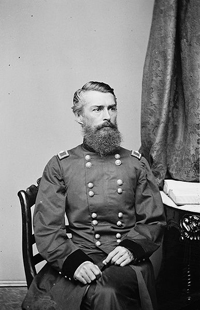

Herman Haupt

Herman Haupt was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on March 26,1817

and was the son of Jacob and Anna Margaretta Wiall Haupt. His father

was a merchant and died in 1829 leaving his mother to support three

sons and two daughters. To earn money for his school tuition Haupt

worked part-time. In 1831, Haupt was appointed to West Point by

President Andrew Jackson and graduated in 1835 but in September he

resigned his commission to become an assistant engineer. He surveyed

several railroad lines including one that went from Gettysburg to

the Potomac. Herman Haupt was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on March 26,1817

and was the son of Jacob and Anna Margaretta Wiall Haupt. His father

was a merchant and died in 1829 leaving his mother to support three

sons and two daughters. To earn money for his school tuition Haupt

worked part-time. In 1831, Haupt was appointed to West Point by

President Andrew Jackson and graduated in 1835 but in September he

resigned his commission to become an assistant engineer. He surveyed

several railroad lines including one that went from Gettysburg to

the Potomac.

He married in Gettysburg in 1838 to Ann Cecelia Keller, and they

would have seven sons and four daughters. In 1839, Haupt patented a

bridge construction technique called a Haupt Truss. His first book

was published in 1840 and titled Hints on Bridge Building. These

must have been great hints. Two of the bridges that he designed and

built in 1854 are still standing in Altoona and Ardmore,

Pennsylvania. Haupt was appointed a professor of mathematics and

engineering at Pennsylvania College in Gettysburg.

He returned to private business in 1847 and became construction

engineer on the Pennsylvania Railroad. He designed the Horseshoe

Curve, a National Historic Landmark, that enabled the Pennsylvania

Railroad to cross the Allegheny Mountains and reach Pittsburgh. With

the publication of his book, General Theory of Bridge Construction,

he established himself as the foremost authority on the subject.

By 1851, Haupt was promoted to superintendent of the Pennsylvania

Railroad. He resigned in 1856 and went to Massachusetts in order to

start a new project. It was a time consuming and a very complex one.

Despite construction difficulties and criticism, he engineered and

helped finance the five-mile Hoosac Tunnel in the Berkshires from

1856 to 1861. Freight trains still use the original Tunnel that was

constructed.

In the spring of 1862, the War Department organized a new bureau

responsible for constructing, maintaining, and operating military

railroads. Haupt was appointed with the rank of colonel to repair

and fortify war-damaged railroad and telegraph lines. He safeguarded

the Washington area by building blockhouses at vulnerable points and

constructing stockades around machine shops. He also armed and

drilled railroad personnel in order to defend themselves. His

spectacular success in repairing damaged lines and bridges was a

result of his personal supervision and detailed inspections.

President Lincoln observed, “That man Haupt has built a bridge four

hundred feet long and one hundred feet high, across Potomac Creek,

on which loaded trains are passing every hour, and upon my word,

gentleman, there is nothing in it but cornstalks and beanpoles.” It

was a wooden bridge.

Haupt was promoted to brigadier general on September 5, 1862, but

refused the appointment. He said that he would be happy to serve

without rank or pay so he could work in private business.

This was true but he also disliked the protocols and discipline of

military service. His construction corporation had three hundred men

and were responsible for the construction of freight cars, barracks,

wharves, and warehouses. Although he was creating and building,

Haupt was also experimenting with various methods of bridge

demolition by using torpedoes that could be used against Southern

railroads.

In the early autumn of 1863 Haupt was offered another promotion, but

he declined and left the service. The Civil War was one of the first

wars to use large-scale railroad transportation to move and supply

armies over long distances. Haupt assisted in many campaigns

including Gettysburg. He quickly organized trains to keep the army

supplied and transport the wounded to hospitals.

After his war service Haupt returned to railroad, bridge and tunnel

construction. He invented a drilling machine that won first prize at

the Royal Polytechnic Society of Great Britain and proved the

practicality of transporting oil by pipelines.

Haupt became wealthy from investments in railroads, mining, and real

estate, but lost most of it due to political skullduggery and

malfeasance involving the completion of the Hoosac Tunnel. Earning

very little from his investments and positions that he held, began

writing. He published books on tunneling, mass transit, and his

early career. In his final decade he depended on the largesse of

friends.

Haupt died of a heart attack on December 14, 1905 in Jersey City,

New Jersey. He was traveling from New York to Philadelphia on a

Pullman car named Irma. He is buried in West Laurel Cemetery in Bala

Cynwyd, Pennsylvania. His son Lewis M. Haupt was a noted civil

engineer and professor.

MARCUS JOSEPH WRIGHT

Marcus Joseph Wright was born on June 5, 1831, in Purdy, Tennessee

to Benjamin and Ann Wright. His father was an officer in the war

against the Creek Indians (1813-14) and served in the Mexican

American War, and his grandfather was a captain in the Revolutionary

War. Wright was educated at a local academy, then studied law, and

was admitted to the Bar. He was clerk of common law and chancery

court and also volunteered in the 154th Tennessee militia and had

the rank of lieutenant colonel. When the Civil War began, his

militia unit was renamed the 154th Senior Tennessee Infantry and

entered Confederate service in April, 1861.

Governor Isham G. Harris of Tennessee ordered Wright to establish a

fortification at Randolph, Tennessee. Fort Wright was the state’s

first military training camp and named after Marcus Joseph Wright.

It has been referred to as a “military laboratory.” Using a variety

of methods, raw recruits were trained to be disciplined soldiers.

Some of the training was traditional and some not so traditional.

The town of Randolph was decimated during the War and all that

remains today is a powder magazine.

The Diary of Brigadier General Marcus J. Wright, CSA was written by

Wright and eventually published. It follows his movements from

April, 1861 to February 1863. The entries are sparse but he writes

about his participation in battles, the dates, and the number

wounded and dead. Wright led the 154th through the Battle of Belmont

(Missouri, 1861). He also fought at Shiloh (April, 1862) where he

was wounded. General Polk next assigned Wright as military governor

of Columbus, Kentucky. He served there until it was evacuated by the

Confederates.

During the Southern invasion of Kentucky (September and October,

1862), Wright served on the staff of Major General Benjamin F.

Cheatham. Wright saw action at the Battle of Perryville

(October,1862) and recalled that it was “one of the fiercest on

record.” In November 1862, he was in charge of post and camp

instruction in McMinville, Tennessee. Wright was promoted to

brigadier general by order of Jefferson Davis.

In 1863-64, Wright was in charge of the Atlanta District. After the

evacuation of Atlanta, he commanded the Macon, Georgia. Toward the

end of the War, he oversaw the North Mississippi and West Tennessee

areas. After the War he was paroled on May 19,1865 at Grenada,

Mississippi.

Wright returned to Memphis and had a varied career. He practiced

law, was the editor of the Journal newspaper in Columbia, Tennessee,

and was sheriff of Shelby county (1870-72). He was also an assistant

purser of the U.S. Navy Yard in Memphis until 1878 which was a

fortuitous

year for him. Wright was appointed agent of the U.S. War Department

to collect all and any Confederate records. He was totally dedicated

to this project and worked on it until 1917.

Wright moved to Washington, D.C. and devoted himself to the

preservation of records pertaining to the War as well as writing

numerous other books. He was one of the main compilers of the War of

the Rebellion Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies.

This was a 128-volume work that is a leading source of the history

of the War. In 1911, he published General Officers of the

Confederate Army and is still considered a valuable resource in

historical research.

If you have a copy of the Memoirs of Robert E. Lee, please look in

the forward. General A.L. Long and Marcus Joseph Wright helped

prepare the book for publication. Other books written by Wright

include: Life of General Blount, Life of General Scott, Analytical

Reference, Tennessee in the War, and The Social Evolution of Women.

The last book must have been very interesting.

Wright was married twice. His first wife was Martha Spencer Elcan

Wright who died in 1875. He then married Pauline Womack Wright

(b.1845-d.1935). He had three sons and two daughters. Wright died on

December 26, 1922 at his home in Washington, D.C. He is only one of

two Confederate General Officers buried at Arlington National

Cemetery. The other was Joseph Wheeler.

Last changed: 09/21/20 |