The President’s Message:

It is a short message this month.

We will have some rare and interesting books for sale at the

March meeting. Dues are

due.

Gerridine LaRovere

March 8, 2023 Program:

The March speaker will be Robert Krasner.

His program will be

The Life of William Barker Cushing.

He is known for his daring midnight raid on the Albemarle on

October 27, 1864. Robert

will talk about the Commander’s sudden dismissal from the Naval Academy

yet becoming one of the most heroic figures during the Civil War.

February

8, 2023 Program:

The

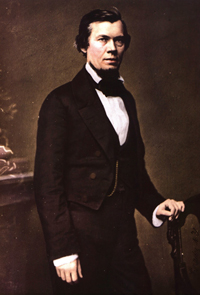

Round Table Players presented a play in one act,

Halos or Horns,

about a Planter, Traitor, Lawyer, or Spy.

Gerridine LaRovere and William McEachern delivered a living

history play about Jacob Thompson, a Confederate officer and politician

who may or may not have stolen over one million dollars from the

Confederate treasury. It

took the form of an interview between a Yankee newspaper reporter and

said “interesting” gentleman.

Due to the availability of Thompson’s script, I have no records

of the reporter’s questions and comments. The

Round Table Players presented a play in one act,

Halos or Horns,

about a Planter, Traitor, Lawyer, or Spy.

Gerridine LaRovere and William McEachern delivered a living

history play about Jacob Thompson, a Confederate officer and politician

who may or may not have stolen over one million dollars from the

Confederate treasury. It

took the form of an interview between a Yankee newspaper reporter and

said “interesting” gentleman.

Due to the availability of Thompson’s script, I have no records

of the reporter’s questions and comments.

I was born in Leasburg, North Carolina in 1810 to Nicolas Thompson and

Lucretia (van Hook) Thompson.

My father accumulated a large fortune by farming, tanning

leather, and harness making.

He was known for being thoroughly honest and upright in all his

dealings. I learned that

from my father.

I

was one of eight children, all but one moved to Mississippi.

All of my siblings were successful people.

Two of brothers, William and George Nichols, became lawyers.

The eldest, Joseph Sidney, became a successful merchant but

remained in Leasburg, NC.

Two of my brothers, James Young, and Josh became prominent physicians.

My two sisters, Ann and Sarah both married well into wealthy and

prominent families. I

was one of eight children, all but one moved to Mississippi.

All of my siblings were successful people.

Two of brothers, William and George Nichols, became lawyers.

The eldest, Joseph Sidney, became a successful merchant but

remained in Leasburg, NC.

Two of my brothers, James Young, and Josh became prominent physicians.

My two sisters, Ann and Sarah both married well into wealthy and

prominent families.

As a child, I attended the Bingham Academy in Orange County, North

Carolina. My family was a

wealthy family, one of the wealthiest in the South.

I am proud to say that both of my parents were of Scottish

descent. Later I entered

the University of North Carolina when I was 17.

I went on to graduate from the University of North Carolina in

1831. I was first in my

class. While I was in

college, I thought about becoming a minister.

At UNC, I was a member of the Philanthropic Society.

There was always a severe rivalry with the Dialectic Society.

Being a Phi was one of the best experiences of my life.

I learned how to debate and orate and I made many lifelong

friends. My debating

experience served me well in my political career and in my legal career.

As I said, I graduated in 1831.

I was asked to be a member of the faculty, which was a great

honor. I served for 18

months. Then, I studied law

with the noted attorney James M. Dick in North Carolina.

I was admitted to the bar in 1834 and commenced practice in

Pontotoc, Mississippi. My

brother, James Young, who was a physician, suggested that I settle

there.

1835 was a very important year in my life.

I had moved to Mississippi.

I speculated, successfully, in land around Natchez, when the

Chickasaw Indians ceded lands to Mississippi.

I bought choice plots of land in the northern part of the State.

My friends would not let me keep out of politics.

Further, it was the custom, in my era, that wealthy men would

find a career in politics.

Our community was soon divided on the question as to whether the State

should endorse the Union Bank bonds for $5,000,000 or not.

The first political speech I ever made was at a meeting held at

Pontotoc for the purpose of favoring that policy and instructing the

representatives in the Legislature to vote for the endorsement.

I opposed the resolution in a strong and able speech, which

attracted attention throughout the State.

I denounced the banking mania which was running riot over

Mississippi, and predicted that the sequence would be overwhelming ruin

and universal bankruptcy.

The resolutions were adopted, however, but in a short time the whole

State had serious cause to regret that my warning had not been heeded.

I was then elected to my first of six terms in the US Congress.

I made my home in Oxford, Mississippi. In 1837, I was not

re-elected to Congress. But

I spent my time wisely, for I courted and married my “beautiful Kate”,

that is Miss Catherine Ann Jones, who was 17, in 1839.

My “beautiful Kate”, came from a wealthy planter family with

extensive land holdings.

She had attended finishing school in France for two years before we

married. She brought a

trunk of gold as her dowry.

Together we built

Home Place,

our plantation in Mississippi.

We owned three plantations in total.

We had one child, Caswell Nacon Thompson.

In addition, my law practice boomed. I also became the State Leader of

the Democratic Party. I

seemed to be destined for great things.

I was elected to Congress in 1839 and served five terms until

1847. These were tumultuous

times. During my time, I

tried to exert powerful influence in our Nation’s capital while Webster,

Clay, and Calhoun were crossing swords.

For example, I was in Congress when Texas was admitted as a slave state.

President Polk signed the resolution to accomplish this.

But issues with Texas, as to her claims to lands north and west

of her, were not resolved until the Compromise of 1850, which was after

I left Congress.

Back home, the Union Bank became utterly bankrupt.

The bonds of the Bank which the State had endorsed, and on which

the Bank had raised capital to run its career, had been dishonored and

the State was called upon to renew its endorsement.

The Governor had refused payment on the ground that the State was

not legally or morally bound, and an appeal was made to the people.

I was called upon for my views. I supported the Governor in his

refusal to honor the bonds.

My letter to the Governor setting forth this position was so clear that

my views were accepted by the people and were adopted by the Legislature

of the State.

In 1844, I did a great deal to secure the nomination of James K. Polk

over Henry Clay. As I said,

I had crossed swords with Mr. Clay over Texas and I was determined that

he would not be president.

Clay had opposed the annexation of Texas, which I supported.

I co-authored a letter with Robert J. Walker which made Texas the

issue of the election and which assisted Polk to be elected.

After Polk had been elected, Polk told Robert J. Walker that he could

only offer him the Cabinet position of Attorney General.

Walker felt that this position was not prestigious enough and

wanted a higher cabinet position. I exercised my powers of persuasion

and induced Polk to grant him the position of Secretary of the Treasury.

Walker proclaimed me as his best friend and said that he would

never forget what I had done for him.

Unfortunately, Walker later proved to be an unprincipled

office-seeker and was basely ungrateful to me. I never spoke to him

again. I viewed him as

being a vile varmint.

I was appointed as Senator in 1845, but to my bitter disappointment, I

never received my commission, so I was never seated.

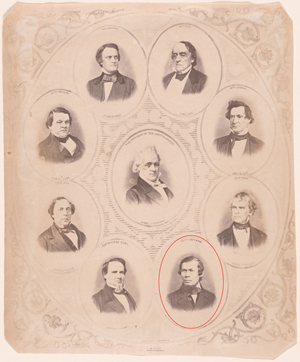

In 1853, President Franklin Pierce offered me the Consular Office

in Havana, Cuba. This

position was considered to be the grandest political prize of all.

I thought that I would lose my law practice if I went and besides

my extensive land holdings and plantations would have suffered.

In addition, I wanted to stay with my wife at our home -

Home Place.

My disappointment over not being appointed to the Senate was later

compounded when I ran for Senator in 1855 and lost to Jefferson Davis.

In 1856, I supported James Buchanan for president.

In

1857, I was appointed as the Secretary of the Interior by President

Buchanan. I was glad to

serve my country and my president.

I found the Department a mere aggregation of bureaus, working

entirely without concert, and the Secretary a mere figurehead.

I was quite an executive.

With my old-time energy, I went to work and infused new life into

every department and united all the business under one head, with me as

the director. The

department grew in favor and popularity with the whole country.

The business transacted by it was enormous.

The volumes of the decisions of Secretary Thompson in law cases

alone were larger than those of the Attorney General. In

1857, I was appointed as the Secretary of the Interior by President

Buchanan. I was glad to

serve my country and my president.

I found the Department a mere aggregation of bureaus, working

entirely without concert, and the Secretary a mere figurehead.

I was quite an executive.

With my old-time energy, I went to work and infused new life into

every department and united all the business under one head, with me as

the director. The

department grew in favor and popularity with the whole country.

The business transacted by it was enormous.

The volumes of the decisions of Secretary Thompson in law cases

alone were larger than those of the Attorney General.

But that was when my name was sullied with the taint of embezzlement.

The Appeal and Disbursing clerk in my bureau stole bearer-bonds

from our safe-almost $3,000,000.

The minute I found out about the empty safe, I went to the

Secretary of State and the Attorney General.

The clerk finally admitted to the theft after an investigation.

The report, issued in late January 1861, concluded that “no one

discovered anything to involve the late Secretary, Honorable Jacob

Thompson, in the slightest degree in the fraud…”

This was damning by faint praise.

Most people concluded that I was involved but they just had not

found the evidence! I

viewed this as being just the way we expressed ourselves at the time.

While still serving as Interior Secretary, I was appointed by the State

of Mississippi as a "secession commissioner" to North Carolina, with the

task of trying to convince that state to secede from the Union in the

wake of the 1860 presidential election.

On December 17, I passed through Baltimore on the way to North Carolina.

"Secretary Thompson has entered openly into the secession

service, while professing still to serve the Federal authority," the

New York Times

reported on December 20.

The next day, I met with Governor John W. Ellis in Raleigh.

He wrote an open letter to Ellis which was published in the

Raileigh State Journal

on December 20. Thompson

wrote that the South faced "common humiliation and ruin" if it remained

in the Union. I warned that

a Northern "majority is trained from infancy to hate our people and

their institutions" and would overthrow slavery.

The result would be "the subjugation of our people."

I resigned as Interior Secretary on January 9, 1861.

When I resigned, Horace Greeley's

New-York Daily Tribune

denounced me as "a traitor", remarking,

"Undertaking to overthrow the Government of which you are a sworn

minister may be in accordance with the ideas of cotton-growing chivalry,

but to common men cannot be made to appear creditable."

I categorically state I was not a traitor.

I was loyal to my state of Mississippi, and to the new nation of

which my state was a part, the Confederate States of America.

I have always been unwaveringly a states’ rights advocate. It is

my state over the central government every day and always!

Still, people claimed that I informed the State of South Carolina that

the

Star of the West

was bound for Charleston’s Fort Sumter, even though that decision was

made by President Buchanan days after I had resigned and weeks after I

had left Washington!

I became Inspector General of the Confederate States Army.

Though not a military man, I later joined the army as an officer

and I served as an aide to General P.G.T. Beauregard at the Battle of

Shiloh. I was wounded at

the Battle of Water Valley, Mississippi in 1862.

My horse was shot from under me and I was wounded.

I attained the rank of lieutenant colonel and was present at

several other battles in the Western Theater of the war, including

Corinth and Vicksburg. I

was on General Pemberton’s staff throughout Vicksburg. I managed to

avoid capture.

I ran for and won a seat in the Mississippi State legislature in the

fall of 1863. In March

1864, Jefferson Davis asked me to lead a secret delegation in Canada.

The President had heard that several thousands of people in Ohio,

Indiana, and Illinois, were weary of the war and were ready to take up

arms and demand of the United States Government a cessation of

hostilities. The

Confederate Congress had voted an appropriation of $1,000,000.00 toward

arming these people, and directed President Davis to send one of our

most discreet and reliable citizens to Canada, to confer with those who

sympathized with the Confederacy and were willing to aid in bringing the

war to a close. This was a

secret mission and one liable to subject the ambassador to slander and

misrepresentation by the unscrupulous. I hesitated before accepting it.

But I felt it to be my duty to serve my country in any honorable

way possible, and I finally accepted.

I was to be chief Commissioner of this operation and treasurer also.

The other members of my Commission were former US Senator Clement

Clay of Alabama and James P. Holcomb.

Davis’ oral instructions to me were to aid the large resistance

organizations operating in Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois to support the

Confederacy and do what damage I could to the war effort of the Union.

We were to go to Montreal.

I also received written orders from the president, which merely said I

was to go to Canada and carry out President Davis’ oral instructions “in

such manner as shall seem likely to conduce the furtherance of the

interests of the Confederate States…”

There have been allegations that I absconded with the money with which I

was entrusted by Davis, some $900,000.00. (This would be worth

$18,374,979.60 today!) (This would be a weight in gold of 3260.13

standard pounds!) These are

founded upon the fact that I never gave an accounting of the

distribution of these funds.

But I swear that every penny was spent doing the work for the

salvation of the Confederacy.

I will try as far as I can to list the distributions of the funds

as best I can.

I ran the blockade at Wilmington, N. C., and sailed on the

Alpha

to Halifax, Nova Scotia; from thence I went to Toronto, and then to a

point south-west of Montreal where I could confer with the people of the

States of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois.

At Toronto, Clay, claiming being ill, refused to go further to

Montreal and demanded that $95,000.00 be put in a personal bank account

in a Toronto Bank. Toronto

was a dangerous place to be: it was filled with Yankee spies!

After much hesitation, I did so.

Clay never gave an accounting of this $95,000.00.

I arrived in Montreal in May of

that year. There I was met

by James Holcomb, a member of the Judiciary Committee who was already

present in Canada. He had

been trying to arrange the escape of 400 Confederate soldiers, to no

avail. I also met Captain

Thomas Henry Hines who was military mission authority.

Hines had been with General John Hunt Morgan’s raid and had

escaped capture.

I deposited the remaining $805,000 in a Montreal Bank, which, for some

reason, seems to have lost all its records about my account. So, I do

not have an account for every transaction.

In early June, 1864, I got in contact with Copperheads, Peace Democrats,

Knights of the Golden Circle, Order of the American Knights, the Sons of

Liberty, and others, all of whom were groups that wanted peace, were

sympathetic to the Confederacy, and for various reasons, were opposed to

Abraham Lincoln. Hines was

critical of my liberal distributions of funds.

I thought that I should spread the money around, so whenever a

Confederate came to me with a plot or a plan to disrupt the Union or

otherwise harass Yankees, I bankrolled it.

I freely distributed large amounts such as $10,000 or $50,000 to

such persons.

I met with and gave funds to Clement Vallandigham, the Peace Candidate.

He told the Sons of Liberty, had 40,000 members in Ohio, 50,000 in

Indiana, and 80,000! In Illinois.

There tens of thousands of Confederate prisoners in camps in the

Midwest. I gave in total

$500,000 to the Copperheads in various plots to free Confederate

prisoners, none of which came to fruition.

On June 13, 1864, I met with former New York Governor Washington Hunt at

Niagara Falls. According to

the testimony of the Peace Democrat Clement Vallandigham, Hunt met me,

and talked to me about creating a Northwestern Confederacy, and Hunt

obtained money for arms for insurrection.

I also gave Benjamin Wood, the owner of the

New York Daily News,

money to purchase arms.

I also wanted to buy all the newspapers on sale to prevent

Lincoln’s re-election.

Thereafter, Holcomb and Hine, to whom I gave $25,000, hatched the plan,

which failed, to free Confederate prisoners of war on Johnson's Island,

off Sandusky, Ohio, in September 1864.

I gave funds to John Yates Beall, a Confederate naval hero, to

capture the U.S. Cutter

Michigan,

the only armed ship on the Great Lakes to harass the Yankee ports there

and disturb trade. This

plot, like all the others, failed.

I also arranged the purchase of a steamer, with the intention of

arming it to harass shipping in the Great Lakes.

As usual, this plan failed.

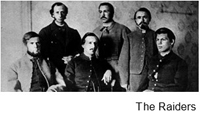

It was at this time, I sent Holcomb and Hines home.

I gave them extensive funds to make the arduous journey running

the blockade. I had been

outfitting, equipping, and otherwise acting as a quartermaster to a

small group of soldiers. It

became too expensive to continue this operation so I disbanded it. It

was led by a Lieutenant Bennet Young.

In

October of 1864 a most unfortunate event occurred, which was not only

without my prior knowledge, but also wholly without my express approval.

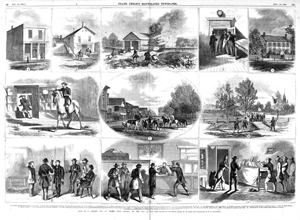

On October 19, 1864, Lieutenant Bennet Young and 20 other

Confederates, disguised as hunters, vacationers, and fisherman slipped

across the Canadian border and entered the town of St. Albans in

Vermont. They robbed three

banks, of $200,000, burned homes and other buildings, killed one

resident and wounded others.

They fled the town followed by a posse which captured some, but

across the border, the raiders were forced to be released by the

Canadian Mounties into their custody. In

October of 1864 a most unfortunate event occurred, which was not only

without my prior knowledge, but also wholly without my express approval.

On October 19, 1864, Lieutenant Bennet Young and 20 other

Confederates, disguised as hunters, vacationers, and fisherman slipped

across the Canadian border and entered the town of St. Albans in

Vermont. They robbed three

banks, of $200,000, burned homes and other buildings, killed one

resident and wounded others.

They fled the town followed by a posse which captured some, but

across the border, the raiders were forced to be released by the

Canadian Mounties into their custody.

The

Union wanted those captured extradited, but Canada refused.

In fact, Canadian authorities contacted me and asked me to supply

funds for the proper defense of these men.

I personally intervened. I gave a speech, behind closed doors, to

the Cabinet. The Cabinet

then issued a decree that the raid was a “hostile expedition by the

Confederate States” and determined that the raiders were acting under

orders. They were soon

released. Canada returned some $88,000 in funds which had been taken

from the raiders. The

remaining $112,000 was never recovered.

I think the townspeople of St. Albans exaggerated the amount

stolen. It has been alleged

that I got the remaining $112,000.00, but this is untrue.

I never had anything to do with this operation. It was done

without my knowledge and permission. The

Union wanted those captured extradited, but Canada refused.

In fact, Canadian authorities contacted me and asked me to supply

funds for the proper defense of these men.

I personally intervened. I gave a speech, behind closed doors, to

the Cabinet. The Cabinet

then issued a decree that the raid was a “hostile expedition by the

Confederate States” and determined that the raiders were acting under

orders. They were soon

released. Canada returned some $88,000 in funds which had been taken

from the raiders. The

remaining $112,000 was never recovered.

I think the townspeople of St. Albans exaggerated the amount

stolen. It has been alleged

that I got the remaining $112,000.00, but this is untrue.

I never had anything to do with this operation. It was done

without my knowledge and permission.

On October 24, 1864, I met with the Peace Candidate for Illinois

Governor, James C. Robinson.

After our talk, I recorded in my journal that I gave him $40,000

for his campaign.

Unfortunately, he got drubbed at the polls.

One plot was a planned burning of New York City on November 25, 1864.

I planned this as just retaliation and retribution for Union

Generals Philip Sheridan and William Tecumseh Sherman's scorched-earth

tactics in the South. I

would note that my home, my favorite plantation, called

Home Place,

in Oxford, Mississippi was burned down by Union troops in 1864.

One Confederate, Robert Kennedy, was captured, tried, and hung

for his activities in the arson.

I was ordered by this time to hatch plots to burn Buffalo, Detroit, and

other cities along the Canadian border.

There have been allegations that I was the leader of Confederate

Secret Service operations in Canada.

That is simply not true.

I was regarded in the North as a schemer and conspirator, many devious

plots were associated with my name, though I am sure that much of this

was public hysteria in the North.

I was simply a soldier doing my duty for his country.

In March of 1865, arrest warrants were issued for me by the Federal

Government. Some have

speculated I met John Wilkes Booth, who assassinated Abraham Lincoln,

but not only has that has not been proved, but also it never happened.

I have spent years after the war working hard to clear my name of

involvement in the assassination.

In actuality, I had been a friend of Abraham Lincoln in Congress.

Just hours before his assassination, he prevented Federal agents

from pursuing me to Europe and arresting me.

After the Civil War, I fled to England for two years and then lived in

France in a sumptuous hotel for three years.

Later I returned to Canada as I waited for passions to cool in

the United States. I

eventually came home and settled in Memphis, Tennessee, where I could

manage my extensive holdings.

I was later appointed to the board of the University of the South

at Sewanee and I was a great benefactor of it.

I

died in Memphis in 1885 and I was interred in Elmwood Cemetery.

Republicans and Union veterans condemned President Grover

Cleveland administration's lowering of flags to half-mast in Washington

and Secretary of Interior Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar II's closure

of the Department of Interior to honor me after my death. I

died in Memphis in 1885 and I was interred in Elmwood Cemetery.

Republicans and Union veterans condemned President Grover

Cleveland administration's lowering of flags to half-mast in Washington

and Secretary of Interior Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar II's closure

of the Department of Interior to honor me after my death.

Last changed: 02/28/23 |