Volume 37, No. 1 – January 2024

Website:

www.CivilWarRoundTablePalmBeach.org

The President’s Message:

The Round Table will not be meeting in July or August.

I look forward to seeing everyone in the fall.

If you have a program you would like to give, please call me at

561/967-8911. We are

scheduling presentations for the coming months and look forward to a

return engagement by Patrick Falci and Robert Macomber.

Gerridine LaRovere

January 10, 2024 Program:

Once again, we have Robert N. Macomber back with us again.

Although most of us are quite familiar with Robert, for our new members he is the author of the

“Honor” series of historical novels. These books, and there are 16

of them at last count, tell the story of the late 19th and early 20th

century via the fictional character of Peter Wake, USN.

familiar with Robert, for our new members he is the author of the

“Honor” series of historical novels. These books, and there are 16

of them at last count, tell the story of the late 19th and early 20th

century via the fictional character of Peter Wake, USN.

Robert has been the recipient of the Patrick D. Smith Literary Award,

the American Library Association’s W.Y. Boyd Literary Award, a Gold and

Silver Medal winner in Popular Fiction from the Florida Book Awards, and

a host of other accolades spanning over two decades. He has earned

rare experiences like being Distinguished Lecturer at NATO HQs

[Belgium], and, for ten years, was invited into the Distinguished

Military Author Series, Center for Army Analysis [Ft. Belvoir]. Robert

was named Florida Author of the Year in 2020 by the FL Writers

Association, and is a captivating storyteller helping spread a love for

history!

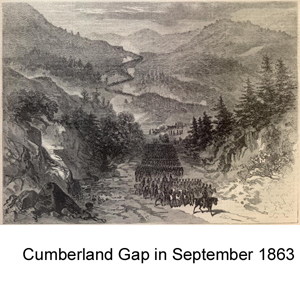

The Cumberland Gap During the Civil War

The Cumberland Gap is 1,304 feet in height and is a natural passage

through the Cumberland Mountains which are between Kentucky, Tennessee,

and Virginia. The Gap is

one of the natural breaks in the rugged Appalachian Mountain Range.

The Old Wilderness Road that cuts through the Cumberland Gap was a

natural invasion. For the

Confederacy, it led to the resources of Kentucky. F or the Union, it

offered an opportunity to cut the enemies supply lines.

In the summer of 1861, Confederate troops commanded by Brigadier

General Felix K. Zollicoffer secured the Gap region and began

constructing fortifications.

The fortress was a single narrow pathway that invaders had to

pass. There was plenty of

timber for campfires, barracks, and other defensive structures as well

as a grand view of the low hills and broad valleys.

By the fall, the new commander of the gap, Confederate Brigadier General

William Churchwell, directed the construction of seven forts on the

north slope and cleared the mountain of all trees within a mile.

This was the first of many scars on the beautiful landscape in

the area due to the War.

The North and South cleared and chopped the terrain.

Eventually, the mountain would be completely devoid of all tress.

On September 9, 1863, a soldier, O.G. Swingburg, from the 125th

Ohio wrote: The trees which

had formerly covered the Mountains were all cut down.

Their trunks lie tangled and scattered in all directions to

prevent rapid charges of infantry.

Surely, a valley of death could not have been more skillfully

constructed. All who walked

that road today would agree that had the charge been made, it would have

been the last road walked in eternity.

It would have been murder to have orders that assault.”

With the forts in place, trenches ringing the mountain, outposts

scattered at the foothills, and a seemingly formidable position,

Churchwell was assured of achieving victory by simply doing nothing.

Inaction can be a poor strategy even if it is the only available

one. When Zollicoffer

reached Kentucky with orders to “preserve peace. protect the railroad,

and repel invasion,” he was killed.

He mistakenly galloped into a mass of Union troops.

The many unfortunate perils of war.

Churchwell was faced with great uncertainty that Union forces would soon

be approaching the Gap. The

Northern soldiers would be assisted by the local population of

Lincolnites who were waiting for the chance to join the blue-clad

warriors.

Northern Brigadier General George W. Morgan soon arrived to take

possession of the Gap. His

plan was to lead his army through Big Creek and Roger’s Gaps which were

west of the Cumberland Gap.

They battled their way through dense woods, thick underbrush, and up

rocky terrain as they hauled cannons and wagons by block and tackle.

Morgan’s weary four columns assembled in the broad Powell Valley.

Then, the General received word that his army was to return to

the other side of the mountain they had just scaled in order to counter

an expected Confederate attack.

It is said that the bark of the surrounding trees blistered off

from the men’s profanity.

Morgan’s brief presence to the west and behind Cumberland Gap showed the

obvious to Churchwell. He

was vulnerable. That was

the problem of the Gap.

While it protected its inhabitants, it also trapped them.

The surrounding mountains made passage difficult but it did not

prevent troop movements.

Finally, Morgan was given permission by General Don Carlos Buell to turn

his troops around, cross the mountain, and go eastward up the valley.

When Federal forces arrived at the Gap on June 17, 1862, they

found the fortifications abandoned.

“The Gap is ours,” Morgan announced, “and without the loss of a

single life.”

Churchwell and his troops were needed elsewhere and the Confederates

abandoned the Gap and headed south in June of 1862.

They spiked five large cannons, destroyed supplies, and cut up

500 tents.

Morgan began building nine batteries to repel an invasion but it never

came. They were determined

to hold the Gap and supplies came down the narrow mountain roads.

A reporter from the Cincinnati Gazette wrote, “During our five

days journey we met at least 500 government wagons and not less than

3,000 mules.” Morgan

estimated that he received enough supplies for 20,000 men for ninety

days. However, he only had

half that number of men.

Pro-Union refugees came to the camp to take up arms but most of them

were in ill health and not incapable of soldiering.

By August, Confederate General Kirby Smith and his troops took a page

from Morgan’s plan book and moved through Big Creek and Roger’s Gaps.

They placed themselves directly behind Morgan.

Confederate forces operating at Barbourville, 24 miles north of

the Gap, severed Morgan’s supply line.

“If you want this fortress, come and take it.” Morgan replied to

a surrender from Smith.

Morgan’s response was heroic.

He had 10,000 troops compared to Smith’s 25,000.

On September 12, 1862 the Union quartermaster reported that

supplies were cut off.

There was no more forage for the horses and mules and the men ran out of

bread. Surrender would have

been the only option if it was not been for Captain Sidney S. Lyon.

He was a former Kentucky surveyor and knew all the minor roads

that wound through the state.

Lyon led the endangered garrison nearly two hundred miles to

safety. The Gap was in the

hands of the Confederates again without a shot being fired.

They cleared the mess Morgan and his men left behind and

strengthened the forts.

There were many skirmishes as Union soldiers from Tennessee raided the

garrison.

In September, 1863, Union forces under the command of a “tall, dapper,

lean-cheeked Irish nobleman” named John Fitzroy De Courcy.

He was ordered by General Ambrose Burnside to take the Cumberland

Gap. On September seventh,

De Courcy destroyed provisions stored at the Iron Furnace which was in

operation from 1820 to 1880 less the Civil War Years.

At the Iron Furnace limestone and iron ore were heated by coal

and converted to ‘pig iron’ which was shipped to factories.

During the Civil War years it became a place to store provisions.

Colonel De Courcy’s men numbered 1700 and were inexperienced.

They also faced a shortage of food, medicine and ammunition.

De Courcy had to convince the enemy that is small command was

much larger than it was. He

divided his men into sections and sent them marching down a hill one

section at a time, in full view of their opponents.

To the rebels the message was clear; they were about to be

attacked by a substantial force made up of infantry, cavalry, and

artillery, however, it would take more than De Courcy’s imagination to

remove the Confederates from their fortifications.

It would take some strong spirits in a bottle.

Confederate Brigadier General John W. Frazier commanded the rebel forces

at the Gap. However, with

the loss of a mill that supplied his men with corn and wheat as well as

the formidable De Courcy forces, he was not in command of his nerves.

Frazier sent Captain Rush van Leer to meet with De Courcy and

begin negotiations. Frazier

reasoned that if the armies were negotiating, they would not be shooting

at each other. A Union

officer offered van Leer a drink of whiskey and suggested that some

other Confederate officers might want a drink as well.

“Fill them to the ears, if you can.” instructed De Courcy.

Van Leer went back up the mountain ladened with whiskey.

The alcohol was dispensed to the rebel officers.

Frazier retired to his tent to think and drink.

The whiskey worked its magic and De Courcy sent a note to Frazier

that said, “It is now 12:30 PM and I shall not open fire until 2 PM

unless before that time you shall have struck all your flags and hoisted

in their stead white flags in token of surrender.”

At 3:00 PM on September ninth, Frazier surrendered the Gap.

As they lined up along Harlan Road, the Confederates were amazed

to see the small force to which they surrendered.

The Gap remained in Union hands until the end of the War.

Except for a garrison inspected by Lt. General Ulysses S. Grant

in January 1864, when he labeled the Cumberland Gap the “Gibraltar of

America.” The area remained

fairly quiet. Grant said

that “with two brigades of the Army of the Cumberland I could hold that

pass against the army which Napoleon led to Moscow.”

Although it was of strategic importance, the Cumberland Gap never

entered history as a momentous battle of the Civil War.

The Gap did change hands four times during the War.

Its isolation led to historical anonymity and eventually nature

reclaimed the land and erased any trace of the fortifications.