June 11, 2025

Program:

Good evening. As you know,

my name is Robert Schuldenfrei.

The topic for this presentation is

Civil War Leaders and West Point.

To illustrate the pedagogy, I have chosen six leaders who I

believe illustrates my point of the influence of West Point on the Civil

War. These generals are

Pierre G.T. Beauregard, Ulysses S. Grant, William J. Hardee, Robert E.

Lee, George B. McClellan, and Phil H. Sheridan.

It would be ridiculous to attribute to West Point the sole reason

for their behavior during the war.

That would ignore their upbringing, social life, the war with

Mexico, and a great number of other factors.

However, my point tonight is that the academy had significant

influence on these men.

The United States Military Academy was founded under the administration

of Thomas Jefferson in 1802.

Its reason for being was to provide a cadre of officers around

which to form a large army in times of emergency.

Right from the start it was to reflect the values of the new

nation by drawing the Corps of Cadets from all classes, not just the

upper classes as was the model of European military schools.

It was to allow the raising of an army when the need arose and

avoid a large standing army.

Often the armies of Europe exploited the societies they were

supposed to defend. America

needed a defense policy that was both revolutionary and rational.

The

first years of the school were really hard ones for West Point.

The academy’s foundation was the Corps of Engineers.

Until Sylvanus Thayer took over as superintendent in 1817 the

school struggled and nearly went out of existence.

He is known as the "Father of the Military Academy."

The principles he laid down formed the basis of the curriculum,

some of which continue to today The

first years of the school were really hard ones for West Point.

The academy’s foundation was the Corps of Engineers.

Until Sylvanus Thayer took over as superintendent in 1817 the

school struggled and nearly went out of existence.

He is known as the "Father of the Military Academy."

The principles he laid down formed the basis of the curriculum,

some of which continue to today

Thayer made civil engineering the foundation of the curriculum.

For the first half century, graduates were largely responsible

for the construction of the bulk of the nation's initial railway lines,

bridges, harbors, and roads.

Many of these works had an impact on the Civil War.

Colonel Thayer's time at West Point ended with his resignation in

1833, after a disagreement with President Andrew Jackson.

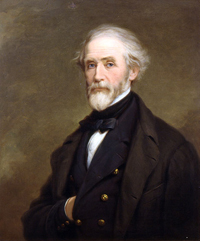

Of our six cadets of interest only Robert E. Lee, class of 1829,

was enrolled during the tenure of Thayer.

It is interesting to note that Lee himself was superintendent

from 1852 until 1855.

No discussion of mid-century West Point would be complete without

introducing Dennis Hart Mahon. He was an instructor

of civil and military engineering from 1824 to 1871.

He is pertinent to our story because historians agree that he had

great influence over all cadets who went on to command during the Civil

War. His focus was on the

teaching of Antoine-Henri Jomini.

This meant the emphasizing combined arms tactics – the

integrating different combat elements, such as infantry, artillery, and

cavalry.

Mahon. He was an instructor

of civil and military engineering from 1824 to 1871.

He is pertinent to our story because historians agree that he had

great influence over all cadets who went on to command during the Civil

War. His focus was on the

teaching of Antoine-Henri Jomini.

This meant the emphasizing combined arms tactics – the

integrating different combat elements, such as infantry, artillery, and

cavalry.

Mahan was known for his discipline, hard work, sternness, and

dedication, traits that defined his teaching approach.

Despite his stern demeanor, he intervened for struggling cadets

and took pride in their achievements, reflecting a mentorship style that

balanced rigor with support.

His role as an instructor at West Point was not merely

educational but transformative, shaping the strategic and engineering

foundations of the U.S. military.

His textbooks, mentorship, and curriculum innovations ensured his

teachings resonated far beyond his lifetime, leaving a legacy that is

studied to this day.

Beyond teaching of principles, facts, and historical references, Mahan

stressed reason and common sense.

Following in the footsteps of Jomini, stressed that speed,

maneuver, logistics, and movement are more important than the

destruction of the enemy.

Lee seemed to take this into account.

His study of Jomini’s interpretations of Napoleon shaped his

preference for dividing enemy forces and striking at weak points.

His campaigns, like the Seven Days Battle in 1862 and

Chancellorsville in 1863, reflected this influence through bold,

aggressive maneuvers and attempts to outmaneuver Union forces, even when

outnumbered. Early in the

war, Lee had been called "Granny Lee" for his allegedly timid style of

command. However, on June

25th, he surprised the Army of the Potomac and launched a rapid series

of bold attacks. The Army

of Northern Virginia move from one battle to the next whether it had won

the fight or not. Lee moved

forward and McClellan moved back.

Chancellorsville was even more dramatic.

Lee had a smaller force than Hooker and yet he divided it such

that he had forces on many sides of the Army of the Potomac.

That day maneuver trumped mass on the field of battle.

Jomini looking down from heaven must have had a smile on his

face.

Grant too, by fighting in all areas of operations at the same time was

able to control all of his forces as one.

He made good use of the new technology of telegraph

communications to bring their forces together for battle.

For example, once Grant got to the eastern bank of the

Mississippi River in the Vicksburg campaign, he was able to operate on

Jomini’s principles of interior lines and maneuver.

He fought a series of battles to the south and east of the city

before the siege and victory.

We also can illustrate the effects of Mahan’s teaching on George B.

McClellan. Mahan taught

McClellan it was better to take strategic points rather that destruction

of armies, unlike Grant.

The academy's emphasis on Jomini’s theories prioritized controlled

maneuver-based warfare and securing key geographic points.

He preferred large, well-organized armies and avoided risky,

aggressive engagements, aiming to outmaneuver opponents strategically.

This influenced McClellan’s cautious, methodical, and

logistics-focused style as a commander.

He did Jomini proud in developing a base of operations.

He built and built up the Army of the Potomac many times under

his tenure.

William J. Hardee influenced the United States Military Academy as a

teacher and was shaped by it as a student.

He literally wrote the book on tactics in his 1855 book Rifle and

Light Infantry Tactics. As

a cadet in the Class of 1838, Hardee’s West Point education provided him

with a foundation in tactics, discipline, and strategic thinking that

made him one of the Confederacy’s most effective corps commanders.

In 1862 Hardee had command of one of the two wings of Bragg's

Army of Mississippi outside of Perryville, KY.

Hardee had selected Perryville for a few reasons.

The village of approximately 300 residents had an excellent road

network with connections to nearby towns in six directions, allowing for

strategic flexibility. It

was located to prevent the Federals from reaching the Confederate supply

depot in Bryantsville.

Finally, it was a potential source of water.

Thanks in part to Hardee’s planning and execution Braxton Bragg

had arguably won a tactical victory, having fought aggressively and

pushed his opponent back for over a mile.

Hardee returned to West Point to serve as Commandant of Cadets in 1856.

He thought that the students should have more instruction in the

art of strategy than they were getting and offered to have the tactical

department provide it. In

the past Thayer made the same proposal.

Professor Mahan protested that he was already teaching the

subject in his engineering classes.

The trouble was that Mahon spent so much time on military and

civil engineering that he only had a few days left over for strategy.

So, in 1860, with the support of Secretary of War Jefferson

Davis, the teaching of strategy was transferred to the tactical

department. Of course,

shortly thereafter Hardee and Davis were both gone.

Ambrose makes the point that in January of 1863, when things were not

going well for the Union, there was the appropriations bill for West

Point on the Senate floor.

Senator Trumball said, emphasis placed by the Academy on mathematics and

fortifications was the cause of the Union’s defeats.

Trumble went on “Take off your engineering

restraints…Dismiss…from the Army every man who knows how to build

fortifications, and let the men of the North, with their strong arms and

indomitable spirit, move down upon the rebels, and I tell you they will

grind them to powder in their power.”

The attempt to destroy the Academy failed.

Some of the Republicans who voted against the resolution noted

that the Yankee armies who were being defeated, after all, by West

Pointers who were displaying imagination and dash, the chief culprit

being former Superintendent Robert E. Lee.

The charges of incompetent training had a false ring.

The North it seemed, had just got the wrong graduates.

Southern graduates did better, in the early years of the war, than their

northern classmates for a number of reasons.

Their troops were better.

The rural South produced soldiers who were used to firearms and

outdoor living. They were

on the defensive and fighting in their own country with short supply

lines and a friendly population.

Until 1863 morale was higher.

Until Halleck and Stanton came to the War Department, the

Confederate Army was better organized.

Confederate cavalry was clearly superior, not only because it was

better led but because the southerners sat on their horses better.

Leaders like Lee, Jackson, and the two Johnstons – were career

soldiers who had served as professional soldiers most of their adult

lives. The leading Union

officers resigned from the Army after the Mexican War to followed

civilian pursuits. George

Thomas was one of the few who remained – Grant, Sherman, McClellan, and

Halleck had all been civilians.

In 1861 they had to readjust, and it took time; the Confederates

did not.

When the tide turned in the summer of 1863 the North had her two

greatest victories, Vicksburg and Gettysburg, both won under

Academy-trained men. The

war was finally being won.

Grant, Sherman, Meade, Sheridan, and other professionals were becoming

heroes; McClellan and Buell, the leading conservative Democrats in the

army, were gone. Halleck

had become a Republican.

The critics left West Point alone.

The focus of a West Point education due to Thayer was built upon the

study of engineering and mathematics.

This approach made a great deal of sense when the regular army

which would receive these cadets numbered a little more than six

thousand in the early 1830s.

Small though it was, this force undertook a variety of tasks.

The regulars’ routine duties included manning the coastal

defenses, exploring, mapping, policing the West and building bridges,

railroads, and canals.

Let’s

focus on mathematics first.

In our time period, there was one teacher who was a standout.

Albert E. Church graduated first in the class of 1828 and was

commissioned in the Artillery, there being no vacancies in the Corps of

Engineers. Thayer requested

that Church stay at West Point to teach mathematics, and there he

remained except for the two years starting 1832, when he joined his

artillery unit. In 1837, he

became professor of mathematics.

Church served as a professor until his death in 1878, a total of

fifty years. Let’s

focus on mathematics first.

In our time period, there was one teacher who was a standout.

Albert E. Church graduated first in the class of 1828 and was

commissioned in the Artillery, there being no vacancies in the Corps of

Engineers. Thayer requested

that Church stay at West Point to teach mathematics, and there he

remained except for the two years starting 1832, when he joined his

artillery unit. In 1837, he

became professor of mathematics.

Church served as a professor until his death in 1878, a total of

fifty years.

A large portion of the Fourth and Third Classes, Freshman and Sophomore,

were devoted to math. It

was indeed impressive. The

cadets took Algebra, Plane & Solid Geometry, Plane & Spherical

Trigonometry, Mensuration (the branch of mathematics that studies the

measurement of geometric figures and their parameters like length,

volume, shape, surface area, lateral surface area, etc.), Analytic

Geometry, and Differential & Integral Calculus.

Mathematics was by far the leading producer of academic

casualties. By itself that

subject accounted for 43% of all failures.

The weakness in math led to failures in other subjects.

This amounted for 35% more leading to the conclusion that 78% of

all academic failures were attributable wholly or in part to

mathematics. In order to

remain high in class rank you had not only to be good in math but to

excel in it.

Three of our six candidates were ranked second in their class at West

Point. Pierre G.T.

Beauregard was 2nd out of 45 in the class of 1838, Robert E. Lee was 2nd

out of 46 in the class of 1827, and George B. McClellan was 2nd out of

59 in the class of 1846.

All three excelled in mathematics.

It has been noted that if you were from a good family and had

excellent early education you probably had a good background in

arithmetic and went on to learn many of the above listed courses in

secondary school.

Beauregard’s artillery setup was a textbook application of his West

Point training and engineering skills.

By encircling Sumter with batteries, he ensured a crossfire that

maximized psychological and physical pressure on the Union garrison.

Here is where Grok was a big help.

The AI provided two pages of information when I asked: “How did

Pierre G.T. Beauregard set up his artillery in order to fire on Fort

Sumter?” After all of the

details, including equations, Grok summarized the answer like this.

“Pierre G.T. Beauregard’s mathematical skills were integral to

the success of the Fort Sumter bombardment.

He applied geometry and trigonometry to position 19 batteries

around Charleston Harbor, ensuring a devastating crossfire.

Ballistic calculations, rooted in projectile motion equations,

guided the accurate fire of mortars, Columbiads, and smoothbores, while

triangulation and range tables enabled precise targeting.

Arithmetic underpinned logistics, from ammunition allocation to

firing schedules, and timing calculations synchronized the 34-hour

barrage. These efforts,

grounded in Beauregard’s West Point training and artillery experience,

forced Fort Sumter’s surrender and marked the start of the Civil War.”

We have already discussed Dennis Hart Mahon and why engineering was the

primary force behind the establishment and continuation of the military

academy. Before developing

the effect on the graduates, let’s first layout what the students were

taught. West Point was

heavily influenced by the French military engineering tradition, as the

U.S. sought to model its military education on the renowned École

Polytechnique. It goes

without saying that French was required because many engineering and

military texts were in French.

The focus was on producing officers capable of designing

fortifications, bridges, roads, and other infrastructure critical to

military and national development.

Almost all of the course work in engineering and its related subjects

like chemistry took place in the second and first class years.

The capstone of the academic program was Mahan’s civil and

military engineering lectures called the science of war.

In the paper and pencil world of the 19th century much of these

studies depended on the student’s ability to draw.

It therefore should come as no surprise that there were whole

courses devoted to drawing and topography.

Technical drawing was emphasized, teaching cadets to create

precise plans and maps.

To see how this curriculum set one of our six on the path to his

downfall consider this story about George McClellan.

He was part of an elaborate team of engineers who went on an

expedition to the Pacific Northwest.

During this journey McClellan gave an early display of excessive

caution which was to mar his performance in the Civil War.

While searching for possible railroad passes through the Cascade

Range, the future commander of the Army of the Potomac failed to examine

what may have been the most suitable one at Yakima Pass in the mistaken

belief that the snow cover was much deeper than it actually was.

Historians note that Grant’s strength lay in his ability to adapt and

learn from observing engineering feats.

An example of this was what he observed in Mexico and how that

was applied in Vicksburg where he oversaw complex siege works and river

crossings. Robert E. Lee's

engineering career before the Civil War spanned military fortifications,

civil infrastructure, and wartime field engineering.

Before ending this section, we should reflect on the West Point

engineer. Many cadets

failed to grasp the practical side of military education because the men

who controlled West Point viewed its mission as being the production of

engineers who could function as soldiers rather than the other way

around.

As we begin to look at military logistics the name Mahan reappears.

As was stated earlier, his impact on the school and its students

cannot be overestimated.

Pre-Civil War logistics education included lessons on the importance of

securing resources, maintaining supply chains, and ensuring efficient

transportation of troops and materials.

The principles of military logistics were taught through a

combination of theoretical lectures and practical exercises.

As you will remember Mahan’s classes were derived from the French

with heavy emphasis on Jomini.

The Frenchman was the master of supply.

Case studies from the American Revolution and the War of 1812

illustrated the consequences of logistical failures, such as General

Burgoyne’s defeat at Saratoga due to overstretched supply lines.

Mahan’s lectures were supplemented by texts like Jomini’s

The Art of War

and Mahan’s own writings, such as

A Complete Treatise on Field Fortification.

These works included sections on logistics, emphasizing the need

for careful planning to support military operations.

Cadets were required to take detailed notes and recite lessons,

ensuring they internalized logistical principles.

As you know full well, at the beginning of the battle the

Confederates were badly undermanned.

The early morning attack looked like the forces of Irwin McDowell

would carry the day.

However, Thomas J. Jackson's Virginia Brigade moved from Winchester,

Virginia, to reinforce Beauregard.

They marched to Piedmont Station and boarded trains on the

Manassas Gap Railroad. The

brigade reached Manassas Junction just before the battle.

From there, they marched to the battlefield around noon, where

Jackson's stand on Henry House Hill earned him the nickname "Stonewall."

George McClellan’s West Point education provided him with a deep

understanding of logistics as the backbone of military success, leading

to a well-organized and supplied army.

It is easy to forget in light of his military failures on the

battlefield, that it was his genius in supply that saved the Army of the

Potomac from ruin in the early days of the war.

In the Peninsula campaign McClellan made sure that 225 tons of

supplies were on hand today, tomorrow, and on and on for the days

between mid-March and the end of July 1862.

The nation built up these supplies, wore them out, and built them

up again time after time during the war.

This is what George McClellan learned at West Point and

demonstrated in the field.

In order to introduce the cadets to the soldier’s life, practical

military skills, and to keep a closer watch on them, Sylvanus Thayer

abolished the practice of annual vacations.

In its place Thayer instituted a summer encampment during which

time the cadets lived in tents, participated in drills, and practiced

tactical movements.

The summer schedule was a busy one.

Drills began at 0530 and continued until 1700 hours.

During the day cadets took instruction in riding, dismounted

drill, infantry tactics, musketry, artillery drill and firing, and

fencing. In addition, the

boys walked guard, served on fatigue details, and of course, parading.

Moreover, the first class devoted a part of the summer to making

rockets, grenades, powder bags, and other munitions in the ordnance

laboratory.

In the fall of 1839 horses were procured and the equitation arts were

taught. Of our six only

Grant, McClellan, and Sheridan had the benefit of this training as they

graduated after the arrival of the horses.

Ulysses S. Grant’s horsemanship skills, refined at West Point

from 1839 to 1843, were a cornerstone of his military success and

personal character. One

small episode will serve to demonstrate Grant’s ability.

During his time at West Point the finest horse was York, a

chestnut-colored animal, seventeen hands high, with a strong will.

York would not tolerate an inferior rider and would through him

off, then go through the remainder of the drill alone, never making a

mistake. His favorite rider

was this young cadet from Ohio.

Once, before the Board of Visitors and a large crowd of

spectators, the riding-master had one of his dragoons hold a pole at

arms’ length above his head, the other end resting against the wall, and

signaled Grant, mounted on York, to jump it.

They cleared the pole, “coming down with a tremendous thud” in a

din of applause. The crowd

called for a repeat, and the team of Grant and York did it three more

times.

Sheridan’s Civil War career began in infantry and staff roles, but his

West Point training in cavalry tactics became critical when he was

appointed colonel of the 2nd Michigan Cavalry in 1862.

His rapid rise to command the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps

by 1864 under Ulysses S. Grant was fueled by his ability to apply and

innovate upon West Point’s cavalry principles.

His exposure to structured cavalry training gave him a

theoretical and practical understanding of mounted warfare.

Sheridan transformed Union cavalry from a scouting force into a

decisive combat arm, a shift rooted in tactical foundations but expanded

through his vision. He

integrated cavalry with infantry and artillery, using mounted troops for

shock attacks and raids, as seen in the Yellow Tavern raid in 1864,

where Confederate cavalry leader J.E.B. Stuart was defeated and mortally

wounded.

The last section of this presentation is about character, behavior, and

leadership. When Thayer

came to West Point one of the things that had shocked Thayer’s

systematic mind was the casual manner in which the cadets reported to

duty, attended classes, took examinations, and graduated.

He wanted a system whereby he could eliminate the subjective

opinions of the professors and himself in making corps recommendations

for the graduates. His

solution was the merit roll, a device which allowed Thayer to rank each

cadet within his class, so that at the end of four years he could say

that the cadet ranking first or second in his class should be an

engineer, the highest branch of the army at that time.

And, in similar manner the cadet at lowest position on the honor

role ought to be in the infantry.

This tool practically eliminated all subjective feelings, while

it took into account nearly everything a cadet did for four years, both

in and out of the classroom.

It was the most complete, and impersonal, system imaginable.

Every cadet was graded on every activity, in the classroom and on the

drill field in a positive manner and added to his class rank.

Everything else subjected the student to a black mark which

lowered his rank. In his

subjects, the cadet received marks ranging from 3.0 at the top to 0.0

for a complete failure. The

more points he had the higher he stood.

But, no manner how brilliant he was, his class rank could be

lowered if his behavior was poor.

Thayer had set up a system of demerits for each infraction of the

regulations. Academics

counted to most, but demerit could significantly lower your rank.

Each of the four years had rank for the Corps of Cadets.

Officers came from the first class, sergeants from the second,

and corporals from the third.

The school was organized as a battalion of infantry with four

companies. A cadet Captain

commanded each company, and the senior of the four student officers was

the “First Captain.” There

were many positions filled by seniors who held the rank of cadet

lieutenants. However, there

were still seniors who had “clean sleeves,” but in deference to their

status as seniors they were termed “High Privates.”

It is interesting to note that three of our six subjects, Lee,

Beauregard, and McClellan, all were cadet officers as determined by

their class rank. Grant,

Sherman, and Sheridan were all High Privates.

The merit system did not reward, in fact, it attempted to discourage,

initiative. Had the

regulations been literally and unthinkingly applied, West Point could

have only produced automatons!

That it did not was due less to the system itself than to the

more humane and broad-minded members of the staff.

They refrained from pushing the code to its limits and to the

stouthearted young men who refused to surrender their individuality

regardless of the pressure to conform.

Let’s investigate fighting as an example of bad behavior.

It was a popular pastime.

The antebellum cadet was pugnacious.

His sense of honor was prickly, and an insult or injustice almost

invariably provoked a scuffle.

Usually, the altercations were simple fist fights, resulting only

in bloody noses and black eyes.

Occasionally, the combatants resorted to weapons with intent to

do bodily harm.

Philip Sheridan was suspended for one year after a physical altercation

with a fellow cadet, William R. Terrill.

The incident began when Sheridan, offended by the tone of an

order given by Terrill, a cadet sergeant, broke ranks and threatened to

"run him through" with a bayonet.

The following day, the two engaged in a fistfight.

Sheridan's suspension was a result of this assault on an

upperclassman, which was considered a serious breach of discipline.

It is doubtful that little Phil learned to be pugnacious at West

Point, and further this “bad behavior” served him well when he received

his own command in the war.

We will now contrast Sheridan with that gentleman from Virginia.

As a cadet and superintendent, Robert E. Lee exemplified West

Point’s ideals through his discipline, integrity, and dedication to

duty. His academic

excellence, impeccable conduct, and efforts to mentor cadets set a high

standard. He was a model

cadet, graduating second in his class in 1829 with no demerits over his

four years, an extraordinary achievement reflecting discipline,

adherence to rules, and moral conduct.

His peers and instructors noted his diligence, courtesy, and

commitment to the Academy’s code of honor.

He avoided the infractions like drinking, gambling, or

insubordination, that were common among cadets.

However, his later decision to join the Confederacy raises questions

about loyalty within the framework of West Point’s values, though it

does not negate his earlier alignment with the Academy’s principles.

Lee’s legacy at West Point remains a study in both exemplary

adherence to its ideals and the complexities of applying those ideals in

a divided nation.

Grant fell short of West Point’s ideals of character, behavior, and

leadership. His

accumulation of demerits, mediocre academics, and lack of prominence in

leadership roles reflected a lack of discipline and ambition compared to

the Academy’s high standards.

Grant’s behavior was inconsistent with West Point’s ideal of

disciplined conduct. He

accumulated numerous demerits—mostly for minor infractions like

tardiness, sloppy appearance, or neglecting his quarters—finishing with

218 demerits over four years, placing him near the bottom of his class

in conduct. While he

avoided serious violations, his casual attitude toward Academy

regulations showed a lack of the meticulous discipline West Point

prized.

Drinking was an issue that dogged him all of his life.

For this his detractors have written a condemnation of the

General. That being said,

there is no definitive evidence that Ulysses S. Grant visited Benny

Havens' Tavern while he was a cadet at West Point.

The same could not be said of Sherman who was documented as a

patron of this establishment.

For decades the authorities at West Point tried to close this

“watering hole” without success.

The tavern was so popular it was eventually immortalized by the

ditty, “Benny Havens’ Oh.”

Here is the first verse and chorus:

Verse 1:

Come, fill your glasses, fellows, and stand up in a row,

To singing sentimentally, we’re going for to go;

In the Army there’s sobriety, promotion’s very slow,

So, we’ll sing our reminiscences of Benny Havens, Oh!

Chorus:

Oh! Benny Havens, Oh! Oh! Benny Havens, Oh!

We’ll sing our reminiscences of Benny Havens, Oh!

Returning to Grant he demonstrated character through his personal

integrity and a strong sense of duty during the Civil War.

He accepted the immense responsibility of leading Union forces

with unwavering commitment to preserving the Union.

His willingness to endure criticism and his lack of vanity,

evident in his simple demeanor and focus on results, aligned with West

Point’s emphasis on selfless service.

In the area of behavior, he exhibited the discipline he lacked as a

cadet. His calm under

pressure, clear decision-making, and ability to maintain composure in

chaotic battles like Shiloh, Vicksburg, and Appomattox embodied the

professional conduct West Point sought in officers.

Grant’s leadership as a general is where he most clearly fulfilled West

Point’s ideals. His

strategic brilliance, tenacity, and ability to inspire loyalty in his

troops, despite initial skepticism from superiors, made him one of

America’s greatest military leaders.

He prioritized mission success over personal glory, delegated

effectively, and adapted to modern warfare’s demands, as seen in his

innovative campaigns. His

respect for adversaries, notably in accepting Lee’s surrender at

Appomattox with magnanimity, reflected West Point’s emphasis on

honorable leadership.

Last changed: 04/02/25 |